THE ADMINISTRATION OF OSTIA AND PORTUS

THE MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION

Colony, regions and neighbourhoods

According to ancient tradition (authors such as Ennius, Livius, Cicero and Dionysius of Halicarnassus) Ostia was founded as a colony of Rome by the fourth king of Rome, Ancus Marcius, who was thought to have ruled in the late seventh century BC. Even the year is mentioned: 620 BC.[1] The constitution must have consisted of a lex coloniae, perhaps established when city walls were built in the first century BC. The city was divided into at least five regiones: an inscription from 251 AD mentions a member of the "guild of the five regions" or "guild of the fifth region" of the colony, sodalis corp(oris) V region(um/is) col(oniae) Ost(iensis).[2] The word sodalis may point to a religious aspect of the guild. We hear nothing more about these regions. They were further divided in neighbourhoods called vici. An inscription mentions a fire in a vicus (of which the name is unfortunately lost) in 115 AD, reducing several properties to ashes.[3]

Augustus had divided Rome into 14 regions and many neighbourhoods, but these are known in several Italian cities as well, also in that other great harbour city, Puteoli, where seven or perhaps eight regions are documented. Camodeca has argued that Augustus consciously, symbolically, chose for seven regions in Puteoli and this might also be true for Ostia.[4] The vici are best known because of a cult at crossroads, the compita: the cult of the Lares Compitales and of the household gods of the Emperor. Magistri in charge of this cult are documented in Ostia as well.[5] The documentation outside Ostia indicates that the organizations related to the regions and neighbourhoods must have supported the local administration, for example by overseeing concessions of the water supply.

Duoviri

In the Imperial period the most important municipal officials were the duoviri, the "two-men", mayors we might say. They were appointed for one year, but the office could be held again later in the career. They presided over the meetings of the city council. They were responsible for public contracts and the registration of the ownership of land. They acted as judges, as could other members of the local elite. For trials the Basilica (I,XI,5) would be used, in which the remains can still be seen of the podium that was used by the judges. More serious cases had to be transferred to magistrates in Rome (Ostia was officially a colony of Rome), and the duoviri did not have the power to impose the death penalty on Roman citizens.

A register of properties and inventory of the population were revised every five years, and in those years Emperors or members of the Imperial family could be duovir. Often such an appointment would only be honorary and the actual work would be delegated. But it could also free the way for the Emperor to shape the city from close-by. During the reign of Hadrian large stretches of Ostia were rebuilt, and he was duovir twice.[6]

Quaestors

Next in the hierarchy were the quaestores aerarii, financial officials overseeing the aerarium, the public treasury. The treasury was filled through the income from municipal properties, revenues from the use of the public water supply by private people, fines (such as those following the improper use of tombs), fees for membership of the city council, and gifts by wealthy people. This office too was for one year, but could be held several times. The city treasury was stored in the basement of the Capitolium.

The quaestor alimentorum controlled a special fund that was used for the maintenance of poor children.

The basement of the Capitolium, now used for storage of lead water pipes. In antiquity it was the vault of the city treasury. Photo: Jan Theo Bakker. |

Aediles

Two aediles, appointed for one year, also supported the duoviri. They supervised the public infrastructure, such as public latrines, water supply and drains, and the markets, controlling also the weights and measures.

Curators

Specific tasks could be assigned to curatores. The curator operum publicorum et aquarum is documented, who supervised the public buildings and water supply. The addition perpetuum indicates that it was a post for life. We also hear of a curator tabularum et librorum, an otherwise unknown post, presumably for the control of public records. A curator could also have a special, temporary task. Thus a curator pecuniae publicae exigendae et adtribuendae raised money for games and the restoration of a shrine.

Decurions

The decuriones formed the city council.[7] Final control of the municipal administration rested with them. They could initiate public commemoration of distinguished people: honorary statues, funerals and tombs. They had to give permission for the setting up by others of honorary statues on public terrain.

In order to be admitted one had to be freeborn (which was also true for the sons of freed slaves), at least 25 years old, and wealthy. The council itself appointed new members, by decree (decurionum decreto). The decurions were drawn from the wealthy so-called curiales. An entrance fee had to be paid, called summa honoraria. The strength of the council was 100 members. The appointment was for life.

From the third century the main duties of the decurions were financial. They were responsible for the collecting of taxes, and obliged to make up for shortfalls. They then tried to pass the burden on to others, and started to look for means to evade taxation.[8]

The decurions met in the Curia (I,IX,4). The building was erected at the same time as the Basilica, which is opposite the Curia, on the other side of the Decumanus Maximus. The architecture of the facades of the buildings creates a mirror image. The building is surprisingly small, but this will be less of a surprise for those who have seen the setting of the British House of Commons.

The remains of the Curia, the meeting place of the decurions, seen from the Decumanus Maximus. Photo: Daniel González Acuña. |

Patrons of the city

A high distinction was that of patronus of the city. The patrons may perhaps be compared to modern lobbyists. They tried to further the interests of the city, especially with the Imperial government in Rome. People obtaining this office would be senators and knights from Rome, if possible with an Ostian origin. Having a "network" extending outside Ostia was a prerequisite.

Supporting personnel

In public, two lictores walked before the duoviri, calling out to the people to make way. In Rome lictores carried a bundle of rods with an axe as a sign of power. These were called fasces (the word fascism was derived from it). In Ostia however the axe is missing, and we see bacilli, rods without an axe. The reason for this was that the death penalty could not be imposed in Ostia, for this the city had to turn to Rome. The lictors also executed sentences. Scribae cerarii were responsible for the keeping of public records and accounts, scribae librarii were junior clerks. Viatores were messengers, delivering instructions and summoning people to court. Praecones (a word also used for auctioneers) were public criers. The relative importance of the functions is reflected in a benefaction in the second half of the second century. At that occasion decurions received 550 denarii, cerarii 37,5, lictores 25, and librarii 12,5.[9]

Dedication to the Genius of the decurions of Ostia and to Commodus, by Lucius Laelius sp(urius) f(ilius) Herennianus, scrib(a) cerar(ius). Found in a shop of the House of the Gorgons (I,XIII,6). EDR073671. Photo: Jan Theo Bakker. |

Dedication to the Genius of the decurions of Ostia, by the lictores and viatores. Found in the Baths of the Forum (I,XII,6). EDR031496. Photo: Jan Theo Bakker. |

Work on the public infrastructure was carried out by public slaves and freedmen.[10] They could also have administrative duties or work as superintendent (vilicus). They were organized in a guild, the corpus familiae publicae (or publicorum) libertorum et servorum. Upon manumission a slave owned by the city received the name of the city. Such a coloniae libertus was for example Aulus Ostiensis Asclepiades, who dedicated an image (signum) of Mars to the guild for the well-being of the Emperor.[11] He was custodian of the Capitolium on the Forum (aedituus Capitoli). Portuensis after Portus, the harbour district, is also documented.

The guild of the fullers is called corpus fontanorum in one inscription.[12] Presumably they were responsible for maintenance of part of the public water supply.

Elections

A well-known feature of the walls of Pompeii are the painted electoral slogans. But at the end of the first century, elections had been abolished in Ostia. Duoviri, quaestors and aediles were elected by the decurions. The people of Ostia came together only to approve uncontroversial acclamations (universi cives Ostienses; decreto colonorum). Honours could also be paid to people on popular demand (postulante populo; colonorum consensu). But pressure exerted by the people, with the risk of violent protests and disorder, could be great and decisive.

Pontifex Volcani

Religion was omnipresent in the harbours. The main authority in religious matters in Ostia was the Pontifex Volcani, the priest of Vulcanus. This priesthood was regarded as the climax of a public career and held for life.

There has been much debate about the reasons why the cult of Vulcanus was so important in Ostia. It must go back to the very early history of Rome and Ostia. It has been suggested that it was related to the protection of warehouses from fire, but that seems unlikely, because the earliest Ostia was not yet a maritime hub. It might be related to volcanic activity near Portus, where up to the present day occasionally vents appear, small holes from which gasses and hot mud emerge. A small statue of Vulcanus was found in situ in a fountain-niche in the underground service area of the Terme del Mitra (I,XVII,2).

The small statue of Vulcanus, found in a fountain-niche in the Baths of Mithras. Museum Ostia, inv. nr. 152. |

Praetors and aediles of Vulcanus

The Pontifex Volcani was supported by three praetores and (probably three) aediles sacris Volcani faciundis. These religious offices were held at the start of a public career.

Other priesthoods of the public career

To the early or late stage of a public career could also belong a priesthood in the Imperial cult. In the early Empire the flamen Romae et Augusti, priest of Rome and the Emperor, emerges. Later on flamines appear of individual, deified Emperors, flamen divi Titi for example. The protective Genius of the colony had his own priest: the sacerdos geni coloniae. The nature of the sodales Arulenses and sodales Herculani remains in the dark.

THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

Quaestor Ostiensis

Since 267 BC a quaestor Ostiensis had been appointed by Rome.[13] In the late Republican period he supervised the reception, storage, and transport to Rome of grain from the provinces. In 23 BC the career of Tiberius started with the Ostian quaestorship. The full title was quaestor pro praetore, which means that the quaestor also had judicial powers. One of the quaestors, probably during the reign of Augustus, was honoured by Ostian skippers, naviculariei Ostienses, perhaps bringing commodities from Ostia to Rome, or from Puteoli to Ostia.

In 44 AD the post was ended by Claudius, as part of a bureaucratic reorganization. Officials with a different title were from then on appointed: procurators.

Praefectus Annonae

The presence in the harbours of the central government in the Imperial period is very conspicuous. We do not know what had been written down officially about this presence, and must draw conclusions from the presence of Imperial officials and their activities.

In the early first century AD (perhaps 8 AD) Augustus introduced a new, central office for the grain supply: the praefectus annonae. From then on, Imperial officials active in the harbours (the quaestor Ostiensis, later procurators) were subordinate to the prefect of the Annona. A lead water pipe found on the Piazzale della Vittoria, near the Porta Romana, has the stamp colonia Ostiensis C. Poppaeo Sabiniano praefecto annonae. This points to the presence of an office (statio) of the praefectura annonae in the neighbourhood, in the years 62-70 AD.[14]

Of particular interest is an adiutor praefecti annonae ad horrea Ostiensia et Portuensia, a deputy of the prefect of the Annona in Rome, for the grain warehouses in Ostia and Portus. Apparently, in the last three decades of the second century, work was carried out that went beyond the capabilities, powers or resources of the procurators in the harbours.

The political and economic crisis of the middle of the third century is reflected in the administration of Ostia. After 251 AD references are still found to the ordo decurionum, but not to municipal magistrates. The central government in Rome took over affairs. In the second half of the century control was transferred to the praefectus annonae.[15] He is called curator rei publicae Ostiensium, and his name is found in relation to new buildings, restorations, and the setting up of statues. In the early fourth century Manilius Rusticianus was honoured by the ordo et populus Ostiensium as curator et patrono splendidissimae coloniae Ostiensium. In the late fourth century Ragonius Vincentius Celsus, prefect of the Annona, set up a statue for Rome financed by the civitas Ostiensium. At least from the middle of the fourth century the prefect of the Annona was subordinate to the prefect of the City, the praefectus Urbi. A change seems to have occurred in late antiquity, because during the reign of Honorius and Theodosius (408-423 AD) a vicarius urbis, Flavius Nicius Theodulus, was active.[16] The headquarters of the prefect may have been installed on a forum - not identified yet - built by Aurelianus (Emperor from 270 to 275 AD) near the beach: "He began to construct a Forum, named after himself, in Ostia on the sea, in the place where, later, the public magistrates' office was built" (Forum nominis sui in Ostiensi ad mare fundare coepit, in quo postea praetorium publicum constitutum est).[17] In Portus the prefect of the Annona, Messius Extricatus, is documented in an inscription from 210 AD, and in some inscriptions from the fourth and fifth century.[18]

|

Left: a statue of a prefect of the Annona from the late fourth century, found in Ostia. Museum Ostia, inv. nr. 55. Right: base for a statue, set up in front of the theatre by Ragonius Vincentius Celsus, prefect of the Annona. It was financed by the city of Ostia. Photo: Jan Theo Bakker. |

Procurator annonae

After the cancelling of the function of quaestor Ostiensis Claudius created a new function, that of procurator annonae Ostis or Ostiensis or Ostiae (for the epigraphic evidence pertaining to the procurators see the appendices).[19] The office was held by equites, knights. The holders were men of distinction, with an extensive career (cursus honorum). They were honoured with statues in Ostia and in the provinces: Croatia, Sardinia, Tunisia and Algeria. The focus of their activity must have been on contracts, finances and legal issues, communicating especially with local guilds, and skippers and traders from the western half of the Empire. Inscriptions link them to the Ostian builders (fabri tignuarii), grain measurers (mensores frumentarii), grain merchants (mercatores frumentarii) and river shippers (lyntrarii). On one occasion we see the prefect and the procurator working together: Locus acceptus ex auctoritate Flavii Pisonis, praefecti annonae, adsignante Valerio Fusco, procuratore Augustorum.[20]

One inscription, from the Trajanic period, describes the post as procurator annonae Ostiae et in Portu. Apparently, after the completion of the Imperial harbours, the need was felt to stipulate that the top level work could also pertain to Portus. Here we may think especially of the Wine Forum, situated on a quay of Trajan’s hexagon. On this Forum Vinarium praecones auctioned wine, and bankers and cashiers from Rome could be found there.

|

An honorary inscription for M. Vettius Latro, procurator annonae Ostiae et in Portu. It was found in Thuburbo Maius, 60 km. south-west of Carthage Photos: Wikimedia. |

The title may also be procurator ad annonam, instead of annonae. The description "for the benefit of the food supply", which may have formed part of the official description of the post, creates some distance between the official and his work. It implies that the work was done not only for the Emperor (especially the distributions of free grain), but for the private market in Rome as well. The procurators would then have stimulated and facilitated private commerce.

The office of the procurator may well have been the Schola del Traiano (IV,V,15), together with the adjacent Caseggiato delle Taberne Finestrate (IV,V,18), used for administrative purposes.[21]

The Schola del Traiano, the office of the procurator of the Annona. Photo: Klaus Heese. |

Procurator Portus Utriusque

Claudius also introduced the office of harbour master, called procurator Portus Ostiesis, later procurator Portus Utriusque. The office is known from a few inscriptions only, one from Portus, the place of discovery of the others being unknown. It was held by Imperial freedmen. One person of more distinction, a knight, is documented during the reign of Philippus Arabs in 247 AD, when we are in the middle of economic crisis and related administrative changes. This procurator will have focused on the harbour infrastructure: the lighthouse, the quays, dredging, mooring space, unloading, transhipment, and security.

A small bronze disc (diameter 6.6 cm.), recording Claudius Optatus, freedman of the Emperor, procurator of the Portus Ostiensis. The function of the disc is not clear. Berlin, Antikensammlung der Staatliche Museen. |

The title disappeared in the fourth century, when we hear of a comes portus instead. Also in the fourth century Lucius Crepereius Madalianus was consularis molium, fari et purgaturae, so responsible for the moles, lighthouse, and dredging operations. This function is not documented otherwise and was probably a special appointment.[22]

Supporting personnel of the procurator annonae and the procurator Portus Utriusque

The procurator Ostis ad annonam was supported by tabularii Ostis ad annonam, the procurator Portus Utriusque by tabularii Portus.[23] These men kept the archives. More Imperial tabularii are documented, but without specification.[24] This personnel can be seen at work on a relief from Portus and on a sarcophagus auctioned by Christies in 2016, on which the unloading of amphorae is depicted. The procurator annonae also had an assistant called cornicularius who was at the head of beneficiarii.

Relief from Portus. When cargoes were unloaded in Portus they were registered and checked. Rome, Museo Torlonia, inv. nr. 428. |

Sarcophagus sold by Christies. Provenance unknown. Third century. |

It is not immediately clear for which official some other personnel, also active for the annona, worked. A praepositus mensae nummulariae fisci frumentarii Ostiensis was responsible for an Imperial grain treasury. We hear of a centurio annonae and of a dispensator a fruminto Puteolis et Ostis, a steward of the grain at Puteoli and Ostia. Inscriptions document more Imperial dispensatores. We know that these were always slaves and had financial duties.[25] The title of one Imperial freedman has been explained by Meiggs as a decem milibus modiorum. His task may have been the checking of the required minimum capacity of cargo ships.[26]

Other procurators

Specialized procurators are also documented in the harbours. We hear of a procurator ad oleum in Galbae Ostiae Portus Utriusque. His field of competence was the handling of olive oil, specifically the transport to and storage in the Horrea Galbae near the Monte Testaccio in Rome. Or perhaps these horrea had a counterpart in Portus. For some time special attention was paid to iron mines, witness the appointment of a procurator Augusti ferrariarum et annonae Ostis.[27] Callistus, procurator and Imperial freedman, approved the use of part of an Imperial property in Ostia.[28] The procurator pugillationis et ad naves vagas was in charge of mail transport and special, roaming ships.[29]

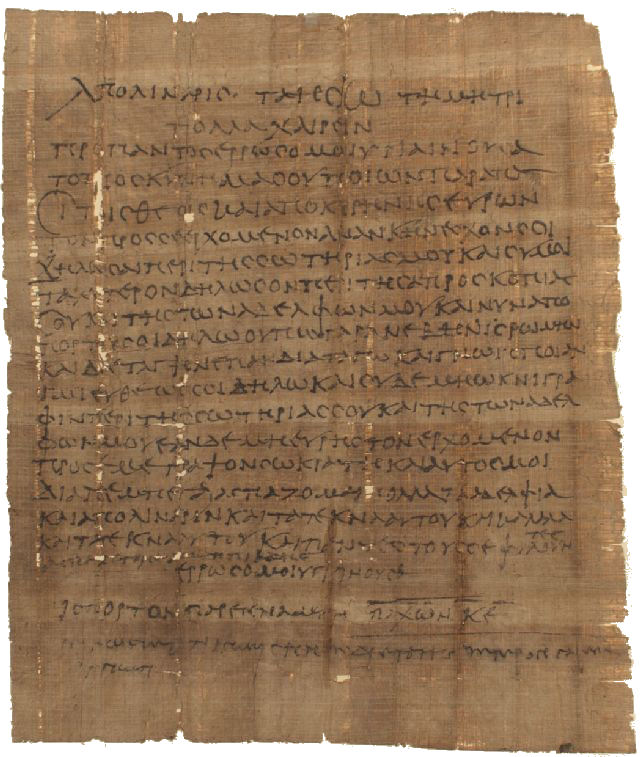

A letter from Apollinarius, sent to his mother in Egypt from Portus, where he had arrived on May 20th, sometime in the second century. Apollinarius to Thaesion, his mother, many greetings. Before all else I wish you good health and make obeisance on your behalf to all the gods. From Cyrene, where I found a man who was journeying to you, I deemed it necessary to write to you about my welfare. And do you inform me at once about your safety and that of my brothers. And now I am writing you from Portus, for I have not yet gone up to Rome and been assigned. When I have been assigned and know where I am going, I will let you know at once; and for your part, do not delay to write about your health and that of my brothers. If you do not find anybody coming to me, write to Sokrates and he forwards it to me. I salute often my brothers, and Apollinarius and his children, and Kalalas and his children, and all your friends. Asklepiades salutes you. Farewell and good health. I arrived in Portus on Pachon 25. (2nd hand) Know that I have been assigned to Misenum, for I learned it later. (Verso) Deliver to Karanis, to Taesion, from Apollinarius, her son. |

An Imperial vivarium was situated to the south of Ostia. Here wild and exotic animals were kept, waiting for transport to the amphitheatre. An inscription from Rome documents a procurator Laurento ad elephantos, an official in charge of elephants, working in the Laurentine territory to the south of Ostia.[30] In the necropolis of Ostia the funerary inscription was found of Titus Flavius Stephanus, freedman of a Flavian Emperor, so in the late first century AD, overseer of the camels (praepositus camellorum). The transport of lions can be seen on a relief found in Portus.

The water supply

Many stamps on lead water pipes in Ostia carry the name of an Emperor (from Caligula to Alexander Severus). Stamps on other pipes (mostly from Ostia, one or two from Portus) document the work of procurators, Imperial freedmen. Sometimes they have the addition a rationibus or patrimonii. These procurators are accompanied by financial officials called rationales, while the Emperor is always mentioned (from Hadrian to Trebonianus Gallus, 251-253 AD).[31] Other pipes register the name of the colonia Ostia. Examples of these pipes, big main pipes, can today be seen in holes left open on the Decumanus Maximus. Still others carry the names of private individuals.

The expressions patrimonium and rationales are linked to the Imperial treasury (fiscus) and properties, offices for which the procurators documented on the pipes worked. Water in Ostia was adduced by aqueducts of Caligula and Vespasian. It remains in the dark whether the Imperial pipes were meant for Imperial properties only, the Baths of Neptune (II,IV,2) for example,[32] or were installed also for the benefit of private organizations that were considered as essential. The work of these procurators in the harbours closely resembles that of colleagues in Rome.

A bronze tap for controlling the water flow in the lead pipes. Photo: Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica. |

The Tiber authority

The control and maintenance of the bed and banks of the Tiber, in Rome, in the harbours, and in between, was in the hands of Rome. The department was led by the curator alvei Tiberis et riparum, "of the bed and banks of the Tiber". His work was practical, comparable to that of the harbour master of Portus. Under his authority boundary markers were set up in Ostia. The ferrymen in Ostia needed his permission for building activity, and the curator also approved the construction of a vigiliarium, possibly a watch-tower. Remains of the quays in Ostia have only been seen in the past. These were mostly destroyed later by the moving, meandering Tiber.

In Rome was a statio alvei Tiberis et cloacarum sacrae Urbis, so including the sewers. The Ostian premises of the assistant of the curator (adiutor curatoris) were called statio alvei Tiberis.[33]

Terracotta statuettes of porters, saccarii. These men carried sacks of grain and amphorae from the warehouses to tow boats, which took the cargos to Rome. Photo: Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica. |

Military men

In the second and third century AD military men called frumentarii were active as project managers, couriers, police, and even spies.[34] Their Roman barracks were called Castra Peregrina, located near S. Stefano Rotondo (the name derives from the provincial background of the soldiers). They had smaller barracks in Portus, called statio frumentariorum.[35] A column on the Piazzale delle Corporazioni carries a dedication to the Genius of the Castra Peregrina by two frumentarii. There may have been a camp in Ostia as well. Here we may think, for example, of building II,XII, partly excavated, but re-interred. It is to the east of the Barracks of the Fire Brigade and presents similarities with that building.

A fire brigade (vigiles) was stationed in Ostia and Portus. Augustus had sent a Praetorian Cohort to Ostia for this work. One of the soldiers (his name is not known) died when fighting a fire, and was given a public funeral by the city.[36] But this cohort returned to Rome by order of Tiberius. Claudius sent an Urban Cohort to Ostia to fight fires. Regular vigiles were sent to the harbours by Domitian, and the earliest phase of the Ostian Barracks of the Fire Brigade, the Caserma dei Vigili (II,V,1-2), has been dated to his reign (81-96 AD). The barracks as seen today were built during the reign of Hadrian.

The vigiles in Ostia and Portus belonged to the Roman cohorts, and came to the harbour city for periods of four months. It was a vexillation of four centuries. Originally 320 men were stationed in the harbours. In 205 AD the number was doubled: 320 men were from now on active in Ostia, and another 320 in Portus.

The vigiles in Ostia and Portus are documented by a wealth of graffiti and inscriptions. The man effectively in charge, both in Ostia and Portus, was called praepositus vexillationis.[37] Particularly dangerous was the work of the sebaciarii, who patrolled at night, either carrying torches or keeping a watchful eye on the illumination of the main streets. It is generally assumed that the vigiles also acted as police. The Imperial cult played an essential role in their life, witness especially a large shrine in the Ostian barracks.

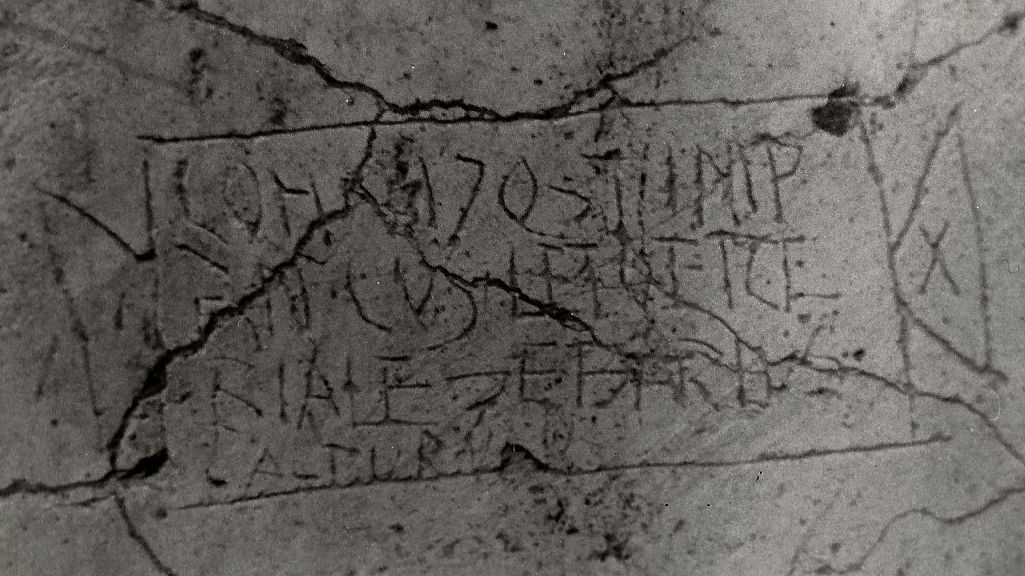

COH(orte) VI (centuria) OST(iensis) IMP(erante) | AN(tonino) CO(n)S(ulibus) L(a)ETO ET CE | RIALE SEBA(cia)RIVS | CALPVRNIVS, X. Sebaciarius Calpurnius, one of the vigiles, left a graffito in a shrine in a bakery. He wished the Emperor, Caracalla, ten more years. He also added a date: the year of consuls Laetus and Cerialis, 215 AD. Photo: Jan Theo Bakker. |

There is furthermore evidence for the presence of military ships in the harbours, from the fleets of Misenum and Ravenna. Presumably they policed the harbours. There must have been military escorts for governors and Emperors travelling by sea.[38] The sailors also took care of the awnings providing shade in the amphitheatre in Rome and presumably the theatre in Ostia. In the Horrea di Hortensius (V,XII,1), opposite the theatre, a navarchus (captain) of the classis praetoriae Misenensis installed a shrine.

Centres of commerce

Two vital centres of commerce were the famous Square of the Corporations,[39] situated in Ostia behind the theatre, and the Wine Forum (Forum Vinarium), situated in Portus. Both are described in detail in separate sections. On the Wine Forum various qualities of wine were auctioned, and bankers from Rome could also be found there. At the heart of the work of the procurators in Ostia, especially the procurator annonae, was the Square of the Corporations. Here representatives were present of a wide spectrum of guilds: local guilds, and guilds of shippers and traders from the Mediterranean basin, from Arles and Narbonne in France to Alexandria in Egypt. On the square the the many organizational and financial issues concerning the maritime import could be solved.

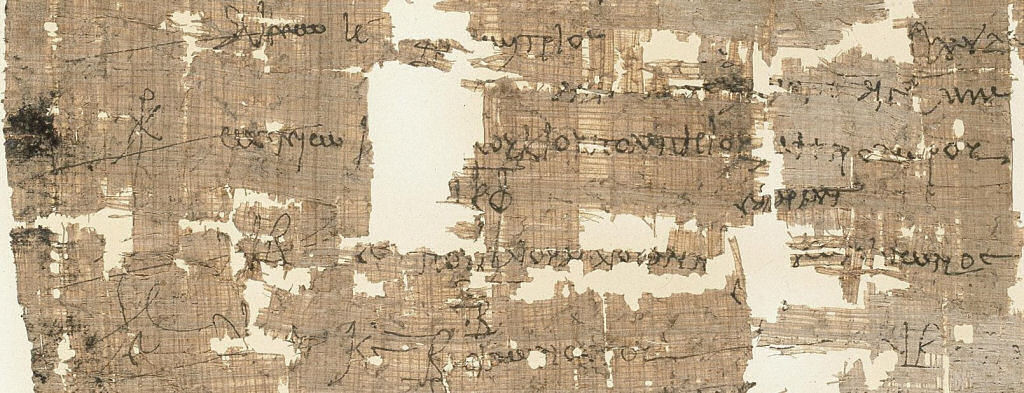

Detail of an Egyptian papyrus, recording the arrival in Alexandria of an empty cargo ship:. "From Ostia. The ship of Lucius Pompeius Metrodoros. 22.500 artabae". The ship could transport c. 585 thousand kg. of grain. |

Salt

Salt was extracted from salt pans near Ostia and Portus. A special case in the administration is the Campus salinarum Romanarum, the salt pans to the north-east of Portus. These seem to have been property of the city of Rome.[40]

THE RELATION OSTIA - PORTUS - ROME - EMPEROR

Looking at the administrative functions in Ostia and Portus, the main outlines of the administration of the harbours seem pretty straightforward. Things are less clear however when we move one level deeper: who owned the various parts of the harbours, and what was the underlying legal status of the land and of the people living and working on it?[41]

The administration was not without tensions. We find some hints in this direction in rather amusing stories about the relationship between Ostia and Claudius. Suetonius informs us that Claudius severely reprimanded the people of Ostia for not sending some boats to meet him when he entered the Tiber (but forgave them later and offered his excuses). Sometime later we hear: "Once, when the men of Ostia made a public petition to him, he lost his temper and shouted from the tribunal that he owed them no consideration, and that surely he was free, if anyone was".[42]

True, Ostia was grateful to Hadrian because he had augmented and preserved the colony, as recorded in an inscription (colonia conservata et aucta omni indulgentia et liberalitate eius).[43] But it feels as if a slight panic had arisen in Ostia during the construction of Trajan’s harbour. Lewis and Short translate conservo as "to retain, keep something in existence, to hold up, maintain, to preserve, leave unhurt or safe". The Imperial government was lying like an octopus over the harbours. What was to be the fate of Ostia after the completion of the vast harbours by the Emperors?

Was the Portus administration based in Ostia?

It is often stated that Portus was part of Ostia until the early fourth century. During the reign of Constantine Portus would then have become an independent city. Russell Meiggs says: "The council and magistrates of Ostia controlled the site" (he means Portus, after the building of Claudius’s harbour),[44] and: "Between 337 and 341 a statue was set up near the harbours to a praefectus annonae by the council and people of Portus, ‘ordo et populus (civitatis) Fl(aviae) Constantinianae Portuenses’.[45] Constantine had made the harbour settlement an independent community". Meiggs explains that the change perhaps took place in 313-314 AD, based on the emergence at a council in Arles of a bishop of Portus, Gregorius.[46]

But then, in his discussion of the cemeteries, Meiggs notes: "At Ostia the fine (he means for improper use of a tomb) was normally to be paid to the Ostian treasury, at Portus to the public treasury of Rome.[47] The distinction between the two centres is embarrassing. One would have expected Portus fines also to go to the Ostian treasury, since the harbour settlement seems to have been controlled by the Ostian government. CIL XIV, 166 is unique in prescribing fines to be paid both to the Ostian and to the Roman treasury".[48]

Many people living and working in Portus were buried on the Sacred Island, between Ostia and Portus. Fines for improper use of their tombs had to be paid to the city of Rome. Photo: Gerard Huissen. |

The second half of the first century

After the completion of the harbour of Claudius by Nero the official name of the harbour was Portus Ostiensis Augusti. Pliny the Elder mentions the Portus Ostiensis.[49] At the end of the century, Quintilianus has Ostia in mind when he mentions the issue an portus fieri Ostiae possit.[50] A Claudian freedman became proc(urator) portus Ostiesis.[51] It would be strange to speak of the "harbour of Ostia" if there was no formal relation between the two. As supporting evidence we may adduce an inscription reportedly found apud Portum Hostiensem, so apparently near Portus.[52] In that case a magistrate from Ostia was active there: it is a dedication to M. Antonius Severus, praefectus fabrum, duovir, quaestor aerarii, quaestor alimentorum, flamen divi Vespasiani, and praefectus fabrum tignuariorum Ostiensium. The priesthood of the deified Vespasian gives it a terminus post quem of 79 AD.

The second and third century

A commentator of Juvenalis’s Satires says: "Trajan restored and improved the Port of Augustus, and made it safer inside, with his name" (Traianus portum Augusti restauravit in melius et interius tutiorem nominis sui fecit).[53] Apuleius describes the arrival in Portus as follows: "Safely driven by favouring winds, I arrived very quickly at the Port of Augustus, and hurried on from there by carriage" (tutusque prosperitate ventorum ferentium Augusti portum celerrime appello ac dehinc carpento pervolavi).[54] The word Ostiensis has disappeared.[55] On coins Trajan called his harbour Portus Traiani. Already during his lifetime it was called Portus Traiani Felicis, the harbour of the happy Trajan.[56] From now on the harbour basins of Claudius and Trajan taken together are called Portus Uterque and Portus Augusti et Traiani felicis.[57] Had Trajan removed Portus from the jurisdiction of Ostia? It looks that way. The consistency of the destination of the funerary fines, the treasury of the Roman people, suggests that Portus was the property of Rome.

A posthumous portrait of Trajan, part of a colossal statue that once overlooked his hexagonal basin in Portus. Rome, Vatican Museums, Museo Chiaramonti. Photo: Wikimedia, Carole Raddato. |

Only one inscription can be adduced as documenting activity by the Ostian authorities in Portus after the construction of the famous hexagonal basin by Trajan. Meiggs, hesitating, suggests that it is from the early third century, after 203 AD.[58] It is a dedication to Serapis in Greek, with permission by the Pontifex Volcani and the duoviri in Latin. The place of discovery however is unknown (it is now in the Capitoline Museums). Carlo Ludovico Visconti hypothesized that it comes from Portus, because of several similar Greek inscriptions found there. But Greek inscriptions related to the cult of Isis-Serapis have also been found in Ostia.[59] Furthermore, the Ostian Serapeum (III,XVII,4) was in a part of Ostia where a considerable number of Greek graffiti has been found. The temple was dedicated on Hadrian's birthday in 127 AD, as formally recorded in the Fasti Ostienses.

The cult of Cybele in Portus was linked to the place. We hear of a female tambourine player (tympanistria) of the mater deum magnae Portus Utriusque and of a priest and flute player (sacerdos and tibicen) matris deum magnae Portus Augusti et Traiani felicis.[60] The importance of Portus was in relation to this cult emphasized in a law: "He who sacrifices in the harbour for the well-being of the Emperor on the basis of foretelling by the high-priest of Cybele receives an exemption from the guardianship" (Is qui in Portu pro salute imperatoris sacrum facit ex vaticinatione archigalli a tutelis excusatur).[61] The names of a few guilds in this cult in Ostia (hastiferi, dendrofori and cannofori) contain Ostiensium.

It seems significant that the cognomen Portensis is documented in Portus and (once) in Ostia, but the cognomen Ostiensis not in Portus.[62]

The unique Trajanic title of the procurator of the Annona, Ostiae et in Portu, could then be a specification that was felt necessary after the administrative division, to clarify that the authority of the procurator still included both centres. Similarly the procurator of the harbours will also have carried out work in Ostia.

The guilds

An intriguing issue is the relation between the commercial guilds of Ostia and Portus. Sometimes the name of a guild consists of the profession only, but Ostia and Portus occur in the name in three variants.

Often only Ostia is mentioned. The builders specify Ostia (collegium fabrum tignuariorum Ostiensium),[63] and so do wine merchants (corpora vinariorum urbanorum et Ostiensium),[64] grain measurers (corpus mensorum frumentariorum Ostiensium),[65] divers (corpus urinatorum Ostiensium),[66] and operators of small boats (corpora lenunculariorum Ostiensium).[67]

Sometimes both Ostia and Portus form part of the name of a guild. This is true for the bakers: we hear of the corpus pistorum coloniae Ostiensium et Portus Utriusque.[68] The furriers (pelliones), who probably made leather reinforcements of sails, formed the corpus pellionum Ostiensium et Portensium.[69] We also have a dedication to the Genius of just the corpus pellionum Ostiensium.[70]

A millstone operated by an animal, inside a bakery in Portus. Museum Ostia, inv. nr. 14263. Photo: Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica. |

The third variant is the existence of separate guilds. This applied to the ship carpenters. Two inscriptions dated April 11 195 AD, the birthday of Septimius Severus, document fabri navales Ostienses and fabri navales Portuenses. In both inscriptions the corpus of Ostia honoured its patron, Publius Martius Philippus, but we read that he was also involved with the corpus in Portus.[71] Either the fabri navales or the fabri tignuarii had their own guild seat (schola) in Portus.[72] In Portus an inscription of the corpus fabrum navalium with a long album was found.[73] The two corpora are documented by quite a few other inscriptions.[74]

Explaining the variants is not easy, because the number of non-funerary inscriptions from Portus is quite small compared to Ostia. Therefore we cannot say that we would expect documentation of a variant in Portus, and then draw conclusions from its absence.

As to the ship carpenters: both guilds had a considerable number of members. The album of the Portus guild preserves the names of 321 members of the plebs, a fragmentary album of the Ostia guild contains 94 names. The Portus guild is special because it had a tribunus, which implies official control and means that the guild had a semi-military character.[75] And this guild had quite a few members who were Imperial freedmen, or their descendants or freedmen, contrary to the Ostia guild. Heinrich Konen has stressed the size and wealth of both guilds, and argues that, whereas ship repairs and maintenance were very important, the most important activity was ship building.[76] The only discernible difference between the guilds seems to be the Imperial involvement with the organization in Portus.

A ship builder at work on a relief from Ravenna. |

At first sight the existence of two different guilds in the same trade may suggest that therefore the bakers and furriers "of Ostia and Portus" formed a single guild, based in Ostia, and active both in Ostia and the harbours. This is a distinct possibility, but not necessarily the case. Certain guilds (collegia) received the status of corpus, "had body" (corpus habere). This happened only when they performed tasks in the public interest, for which also minimum requirements (such as investments) were defined. For the Imperial government a major advantage was that, when concluding contracts, negotiations took place with the corpus only, not with all individual members of the mere collegium. But because regulations were in place, and perhaps also price regulations, the members also received rewards: exemptions from public duties (munera), comparable to our tax deductions. This means that there could easily have been two collegia of bakers and furriers, joined in one corpus, because (and if) the tasks were identical. The reason this was not applied to the fabri navales could be that those in Portus were involved with the building of oared military ships, contrary to their colleagues in Ostia, who built only simpler sailing cargo ships.

The fourth and fifth century

In the fourth and fifth century the harbours of Claudius and Trajan are referred to as Portus Romae. The bishop who appeared at the council in Arles in 314 AD was registered enigmatically as "from the place that is in the Harbour of Rome" (de loco qui est in Portu Romae). A basilica built in Ostia was described in the Liber Pontificalis as follows: "Then the emperor Constantine built in the civitas Ostia close to the harbour of the city of Rome the basilica of the blessed apostles Peter and Paul and of John the Baptist", while the Isola Sacra is called "Assis, the island between Portus and Ostia".[77] The Codex Theodosianus uses Portus Romae and Portus urbis Romae / urbis aeternae / sacrae urbis / venerabilis urbis.[78] In the fifth century Aethicus of Istria says that the Tiber "creates an island between the harbour of the city and the civitas Ostia, which is visited by the people of Rome together with the Praefectus Urbi or a consul to worship the Dioscures with a happy feast".[79] Hieronymus discusses a guest house for pilgrims, a xenodochium, in portu Romano,[80] Marcellinus Comes speaks of Portus urbis Romae.[81]

A mosaic of the Dioscures, Castor and Pollux, in the House of the Dioscures. In the harbours the divine twins were worshipped as protectors of shipping. Photo: Klaus Heese. |

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is a sarcophagus of a physician with a Greek inscription: "If anyone shall dare to bury another person along with this one, he shall pay to the fiscus three times two thousand. This is what he shall pay to Portus, but he himself will endure the eternal punishment of the violator of graves".[82] The sarcophagus has stylistically been dated to the first quarter of the fourth century. The fine is to be paid to the fiscus, the treasury of the Emperor, which is financially equated with Portus. This should not be taken as an indication that the harbour had become Imperial property: fines to be paid to the fiscus are also documented in Rome.[83]

Detail of the sarcophagus in New York. Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

Restorations and dedications in Portus, before and after Constantine, were the work of the Emperor and the Imperial government. We have already seen that a prefect of the Annona, Messius Extricatus, was active in 210 AD (note 18). Septimius Severus repaired a column broken by a storm.[84] In the second quarter of the fourth century a prefect of the Annona erected a statue in the Porticus Placidiana, in honour of Valentinianus III and Theodosius II.[85] It seems to have been a prefect of the Annona who, at the end of the fourth century, restored the temple of Liber Pater in Portus.[85]

Finally: what should we make of the Civitas Flavia Constantiniana with its ordo and populus? In antiquity it is mentioned only once, in the inscription from 337-341 AD. But whereas it is never heard of again in antiquity, it is surprisingly mentioned again as Civitas Constantiniana in documents from 1018 and 1049 AD.[87] This suggests that it existed for a long period of time, but comprised only part of the Portus Romae. The naming of cities after the family of Constantine was discussed at length by Kayoko Tabata. He notes that quite a few cities were named Constans or Constantia or Constantina, one of these also Flavia (Hispellum). One city was just called Flavia (Augustodunum; Autun, France). Only in Portus was the name Constantiniana used.[88] It may have been a residential part of Portus, along the Fossa Traiana.[89]

APPENDICES

Procurator annonae Ostis

|

ID |

Object |

Place of discovery |

Name |

Title |

Date |

Remarks |

|

AE 1939, 81 and AE 1951, 52 = EDCS-08600957/8 and EDCS-33400637 |

Three marble bases with the same inscription |

Thuburbo Maius (Tunisia) |

M. Vettius Latro |

Procurator annonae Ostiae et in Portu |

Around 112 AD (Pflaum) |

Honoured as patronus by two liberti |

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 4467 |

Marble slab |

Ostia, one fragment from the "scarichi lungo il decumano, tra la via dei molini e il foro", another fragment to the east of the museum |

Unknown |

Procurator Ostiae [annonae] |

112-125 AD (Pflaum); 103-125 AD (EDR) |

Honorary inscription; on the other side is CIL XIV Suppl., 4350 from 121 AD |

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 5351 (see also CIL VIII, 20684) |

Marble slab |

Ostia, Terme del Foro |

Unknown |

Procurator annonae Ostiensis |

Middle of the second century (Pflaum); 117-150 AD (EDR) |

Honoured by the collegium fabrum tignuariorum; carries also CIL XIV Suppl., 5352 |

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 5352 (see also CIL VIII, 20684) |

Marble slab |

Ostia, Terme del Foro |

[Annius Pos]tumus? The full name only in Saldae |

Procurator annonae |

Middle of the second century (Pflaum); 117-150 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the collegium fabrum tignuariorum; carries also CIL XIV Suppl., 5351 |

|

CIL VIII, 20684 (see also CIL XIV Suppl., 5351 and 5352) |

Unknown |

Saldae (Algeria) |

Annius Postumus |

Procurator Augusti [ad ann]ona(m) Ostis |

Middle of the second century (Pflaum) |

Honoured by a friend |

|

CIL XIV, 2045 |

Marble statue base |

Ostia, Vicus Augustanus Laurentium |

P. Aelius Liberalis |

Procurator annonae Ostiensis |

End of the reign of Antoninus Pius (Cébeillac-Gervasoni 1994); 140-160 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the vicus, for their patron |

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 4451 |

Marble slab |

Ostia, Piazzale delle Corporazioni |

M. Flavius Marcianus Ilisus |

Procurator annonae [---] |

161-180 AD (Cébeillac-Gervasoni 1994) |

|

|

CIL VI, 1633 (see also AE 1973, 126) |

Marble statue base |

Unknown, in Rome |

C. Valerius Fuscus |

Procurator ad annonam Ostiae |

180-192 AD (EDR) |

Set up by curatores |

|

AE 1973, 126 (see also CIL VI, 1633) |

Marble statue base |

Ostia, reused in the facade of the theatre |

Valerius Fuscus |

Procurator Augg. |

179 AD (Pflaum) |

Adsignante, working for the praefectus Annonae; date preserved only, main inscription removed in antiquity |

|

CIL XIV, 172 |

Marble statue base |

Ostia, reused in the theatre; Piazzale delle Corporazioni |

Q. Petronius Melior |

Procurator annonae |

3 February 184 AD |

Set up by the corpus mensorum frumentariorum Ostiensium |

|

CIL X, 7580 |

Unknown |

Cagliari (Sardinia) |

L. Baebius Aurelius Iuncinus |

Procurator ad annonam Ostis |

Commodus (Pflaum); 196-201 AD (EDR) |

Presumably honoured as prefect of Sardinia |

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 4459 |

Marble base |

Ostia, Terme di Nettuno, probably from the Piazzale delle Corporazioni (LDDDP) |

T. Petronius Priscus |

Procurator Augusti ferrariarum et annonae Ostis |

184-193 AD (Cébeillac-Gervasoni 1994); 151-193 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the lyntr[arii] |

|

AE 1983, 976 |

Unknown |

Maktar (Tunisia) |

Sextus Iulius Possessor |

Procurator Augusti Ostis ad annonam |

171-200 AD (EDCS) |

|

|

CIL XIV, 161 |

Marble statue base |

Ostia, reused in the theatre; Piazzale delle Corporazioni |

Q. Calpurnius Modestus |

Procurator Ostiae ad annonam |

Second half of the second century (Pflaum) |

Set up by the corpus mercatorum frumentariorum |

|

AE 1921, 64 |

Base of limestone |

Salona (Croatia) |

C. Iulius Avitus Alexianus |

[Procurator] ad anno[nam Augustorum) Ostiis] |

198 AD (Pflaum); 219-223 AD (EDH) |

Honoured by a military tribune |

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 5344 |

Marble slab |

Ostia, Terme del Foro |

[...]ius Lollianus |

Procurator annonae Augg. nn. Ostis |

203-209 AD (Pflaum); 205-209 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the fabri tignuarii Ostis |

|

CIL XIV, 154 (see also CIL VIII, 1439) |

Marble statue base |

Ostia, reused in the theatre; Piazzale delle Corporazioni |

Q. Acilius Fuscus |

Procurator annonae Auggg. nnn. Ost, changed to Procurator annonae Augg. nn. p(atrono) c(oloniae) Ost |

198-211 AD (Pflaum) |

Set up by the corpus mensorum frumentariorum adiutorum et acceptorum Ostiensium |

|

CIL VIII, 1439 (see also CIL XIV, 154) |

Base |

Thibursicum Bure (Tunisia) |

Q. Acilius Fuscus |

Procurator annonae Auggg. nnn. Ostiensium, Auggg. nnn., changed to Augg. nn. |

198-211 AD (Pflaum) |

Honoured by the city |

|

CIL XIV, 160 |

Marble slab |

Ostia, scavi Petrini |

P. Bassilius Crescens |

Procurator annonae Aug. Ostis |

219-222 AD (Pflaum); 220-224 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the collegium fabrum tignuariorum Ostis |

|

CIL XIV, 193 |

Base |

Found near Portus |

|

Fragmentary inscription, mentioning the proc. ann. a[---] |

|

|

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 4285 |

Marble statue base |

Portus, loco dicto campo saline |

Sallustius Saturninus and Orfitus |

Procuratores Augg. nn. |

220-224 AD (EDR) |

Questionable; related to the campus salinarum Romanarum; Christol 2018 |

|

AE 1934, 161 |

|

|

Sextus Acilius Fuscus |

|

|

Rejected, incorrect completion; Bruun 2002, 167-168; Christol 2018 |

Procurator Portus Utriusque

|

ID |

Object |

Place of discovery |

Name |

Title |

Date |

Remarks |

|

CIL XIV, 163 |

Small bronze disc |

Unknown. Berlin, Antikensammlung |

Claudius Optatus Aug. l. |

Procurator Portus Ostiesis |

A freedman of Claudius. |

|

|

CIL VI, 1020 |

Marble statue of a woman and statue base |

Unknown, once in Rome, now in Florence, Palazzo Pitti |

Heliodorus lib. |

Procurator P(ortus) U(triusque) |

211-217 AD (EDR) |

Dedication to Vibia Aurelia Sabina, daughter of Marcus Aurelius |

|

CIL XIV, 125 |

Marble slab |

Portus |

Agricola Aug. lib. |

Procurator P(ortus) U(triusque) |

3 August 224 AD |

Locus adsignatus in relation to a statio n(umeri) frumentariorum |

|

CIL XIV, 170 = CIL VI, 1624 |

Marble statue base |

Unknown, in Rome |

L. Mussius Aemilianus |

Procurator Portus Utriusque |

18 May 247 AD |

Set up by the codicarii navicularii et quinque corp(orum) navigantes |

Other procurators

|

ID |

Object |

Place of discovery |

Name |

Title |

Date |

Remarks |

|

CIL XIV, 2045 |

Marble statue base |

Ostia, Vicus Augustanus Laurentium |

P. Aelius Liberalis |

Procurator pugillationis et ad naves vagas |

End of the reign of Antoninus Pius (Cébeillac-Gervasoni 1994); 140-160 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the vicus, for their patron |

|

CIL XIV, 20 |

Marble altar |

Ostia, near Tor Boacciana |

C. Pomponius Turpilianus |

Procurator ad oleum in Galbae Ostiae Portus Utriusque |

161-180 AD (EDR) |

Religious dedication pro salute Imperatoris |

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 4459 |

Marble base |

Ostia, Terme di Nettuno, probably from the Piazzale delle Corporazioni |

T. Petronius Priscus |

Procurator Augusti ferrariarum et annonae Ostis |

184-193 AD (Cébeillac-Gervasoni 1994); 151-193 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the lyntr[arii] |

|

CIL VI, 8583 |

Unknown |

Rome |

Ti. Claudius Speclator Aug. lib. |

Procurator Laurento ad elephantos |

First century AD |

Funerary inscription |

Supporting personnel (selection)

|

ID |

Object |

Place of discovery |

Name |

Title |

Date |

Remarks |

|

CIL XIV Suppl. 4882-4483 |

Funerary inscriptions |

Portus |

T. Flavius Ingenuus Aug. lib. |

Tabularius Portus Augusti |

69-110 AD (Thylander); 69-100 AD (EDR) |

|

|

CIL XIV Suppl., 4319 |

Mable cippus |

Ostia, Piazzale delle Corporazioni |

Traianus Aug. lib. |

Anni decimi magistro or A decem milibus modiorum |

Unknown |

Dedication to the Numen domus Augusti with dispensatores |

|

AE 1948, 103 |

Funerary inscription |

Rome |

P. Aelius Aug. lib. Onesimus |

Tabularius Portus Augusti |

117-170 AD (EDR) |

|

|

CIL XIV, 409 |

Funerary altar |

Probably Portus |

|

Beneficiarii procuratoris Augusti |

135-150 AD |

|

|

CIL XIV, 2045 |

Marble statue base |

Ostia, Vicus Augustanus Laurentium |

P. Aelius Liberalis |

Praepositus mensae nummulariae fisci frumentarii Ostiensis |

End of the reign of Antoninus Pius (Cébeillac-Gervasoni 1994); 140-160 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the vicus, for their patron |

|

CIL X, 1562 |

Marble statue base |

Pozzuoli |

Chrysanthus |

Dispensator a fruminto Puteolis et Ostis |

139-161 AD (EDR) |

Religious dedication pro salute Imperatoris |

|

CIL VI, 8450 |

Funerary inscription |

Rome |

T. Aelius Augg. lib. Saturninus |

Tabularius Ostis ad annonam |

End of the reign of Antoninus Pius (Cébeillac-Gervasoni 1994); 161-169 (EDR) |

|

|

AE 1983, 976 |

Unknown |

Maktar (Tunisia) |

Sextus Iulius Possessor |

Adiutor praefecti annonae ad horrea Ostiensia et Portuensia |

171-200 AD (EDCS) |

|

|

CIL XIV, 125 |

Marble slab |

Portus |

Petronius Maxsimus; Fabius Marona |

Centurio annonae; Centurio operum |

3 August 224 AD |

Working with Agricola, procurator Portus Utriusque |

|

CIL XIV, 160 |

Marble slab |

Ostia, scavi Petrini |

C. Vettius Mercurius |

Cornicularius of the procurator annonae Aug. Ostis |

219-222 AD (Pflaum); 220-224 AD (EDR) |

Set up by the collegium fabrum tignuariorum Ostis |

NOTES

[1] The ancient literary sources about the founding of Ostia are:Ennius, Annales: Ostia munitast; idem (Ancus) loca navibus pulchris munda facit, nautisque mari quaesentibus vitam.

Cicero, De Re Publica II, 18, 33: (Ancus Marcius) ad ostium Tiberis urbem condidit colonisque firmavit.

Cicero, De Re Publica II, 3, 5: In ostio Tiberino, quem in locum ... rex Ancus coloniam deduxit.

Titus Livius, I, 33, 9: In ore Tiberis Ostia urbs condita, salinae circa factae.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, III, 44, 4.

Strabo, V, 3, 5.

Festus: Ostiam urbem ad exitum Tiberis in mare fluentis Ancus Marcius rex condidisse fertur; quod sive ad urbem sive ad coloniam quae postea condita est refertur.

Festus: Quibus (fossis) Ancus Marcius circumdedit urbem, quam secundum ostium Tiberis posuit, ex quo etiam Ostiam.

Florus, I, 4: Ancus ... Marcius ... Ostiam ...in ipso maris fluminisque confinio coloniam posuit, iam tum videlicet praesagiens animo futurum ut totius mundi opes et commeatus illo velut maritimo urbis hospitio reciperentur.

Aurelius Victor, De Vir. Ill. 5, 3: Ostiam coloniam maritimis commeatibus opportunam in ostio Tiberis deduxit (Ancus Marcius).

Servius, Ad Aen. I, 13: Ostiam ... ideo veteres consecratam esse voluerunt ... ut si quid bello navali ageretur ... id ... fieret ex maritima et effata urbe.

Servius, Ad Aen. VI, 815: Hic (Ancus) Ostiam fecit.

Eutropius, I, 5: Ancus Marcius ... apud ostium Tiberis civitatem supra mare sexto decimo miliario ab urbe Roma condidit.

Hieronymus, Chron. a. Abraham 1397: 620 BC.

Isidorus of Sevilla, Etim. XV, I, 56: Ancus Marcius ex filia Numae Pompilii natus: hic urbem in exitu Tiberis condidit quae et peregrinas merces exciperet et hostem moraretur, quam ab ipso situ Ostiam appellavit.

Polybius, VI, iia, 9: foundation by Numa.

Plinius, N.H. III, 56: Ab Romano Ostia colonia rege deducta.

Polemius Silvius, CIL I2, p. 257: (Ostia) quae prima colonia facta est.

There is a complication here. Several ancient authors, beginning with Cicero, state that Ostia was founded by Ancus Marcius as a colonia, a colony. Inscriptions from the Imperial period prove that Ostia was indeed a colony. It is strange however that a very old Roman colony had been governed from Rome until the first century BC. Therefore it has been suggested by Ingrid Pohl that the city became a colonia only in the first half of the first century BC. An ancient author, Festus, wrote: "They say that Ancus Marcius founded the city of Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber where it flows into the sea; by this either the city is meant, or the colony that was founded later". Apparently there were two traditions in antiquity: either the city was founded by Ancus Marcius, but not as a colony, or the city was founded by Ancus Marcius as a colony, that was refounded later. Was the tradition of Ancus Marcius invented or caused by Cicero, builder of the new town walls, the true founding father of the colony?

[2] CIL XIV, 352.

[3] CIL XIV Suppl., 4542.

[4] G. Camodeca, "L'ordinamento in regiones e i vici di Puteoli", in Puteoli romana: istituzioni e società, Napoli 2018, 41-82. Camodeca refers to Léon Homo, Rome impériale et l'urbanisme dans l'antiquité, Paris 1971, 80.

[5] Bakker 1994, 118-133, 195-204, catalogue B.

[6] For the second time in 126 AD. Meiggs 1973, 176. This discussion of the administration of Ostia and Portus uses the work of Meiggs extensively, of course. Specific references would be too numerous. A general overview is Sanchez 2001.

[7] An extensive discussion of the decurions is Caldelli 2008.

[8] An excellent summary of this period is for example "The period from 253 to 268 AD", the first chapter of L. de Blois, The Policy of the Emperor Gallienus, Leiden 1976.

[9] CIL XIV Suppl., 4642.

[10] Sudi-Guiral 2007; Bruun 2008.

[11] CIL XIV, 32.

[12] CIL XIV Suppl., 4573.

[13] See Chandler 1978 for a detailed discussion. More recently Cébeillac-Gervasoni 2014.

[14] Cébeillac-Gervasoni 2000; Bruun 2002, 164.

[15] Meiggs (p. 186) suggests that one of the first prefects with this role was Flavius Domitianus, documented in CIL XIV Suppl., 5342: Flavio Domitiano, praefecto annonae, curatori honorificentissimo, ordo decurionum.

[16] Manilius Rusticianus: CIL XIV Suppl, 4455, found on the forum; Ragonius Vincentius Celsus: CIL XIV Suppl., 4716, found in front of the theatre; Flavius Nicius Theodulus: CIL 14 Suppl., 4720, found in the area of the forum.

[17] SHA, Aurelianus 45,2. See also David - De Togni 2018.

[18] Messius Extricatus in 210 AD: EDR076710.

[19] I only offer my own interpretation of the procurators here. Since the early 20th century there has been an extensive but inconclusive debate about the procurator annonae and procurator Portus Utriusque. A good starting point is Houston 1980. Then Bruun 2002, Caldelli 2014, most recently Christol 2018.

[20] AE 1973, 126; Seston 1971, 330-331. A marble statue base, reused in the facade of the theatre of Ostia (179 AD).

[21] Bocherens 2018 with Mainet 2018 and Aubry 2018. They propose a late-Severan date instead of the period of Antoninus Pius on the basis of brick stamps. On the early date Blake 1973, 213: "The brickwork is characteristic of the period".

[22] CIL XIV Suppl., 4449. Meiggs 1973, 170.

[23] Only Portus Augusti is documented. One of them was a freedman of Hadrian, so there is no need to think of the disappearing of the procurator Portus Utriusque in the second century, as has been suggested by some.

[24] CIL XIV, 49 (T. Flavius Aug. lib. Primigenius, tabularius adiutor), 200 (Fuscinus Aug. lib., tabularius adiutor), 205 (Aug. lib.), 304; CIL XIV Suppl., 4316 (Hispanus Aug. lib., tabularius); Thylander A256 (Hermes Caesaris nostri verna, tabellarius), A279 (Maternus Aug. lib., tabellarius).

[25] CIL XIV, 202 (Genialis, Augusti dispensatoris vicarius), 204 (Caesaris nostri dispensatores), 207; CIL XIV Suppl., 4319 (Victor et Hedistus vernae, dispensatores; dedication to the Numen domus Augusti). Bruun 1999.

[26] Meiggs 1973, 301.

[27] It is not clear whether Dorotheus Aug. lib., procurator massae Marianae, procurator of metal mines in Spain, carried out his work in Ostia-Portus (CIL XIV,52; 151-230 AD). The same may be said about Hilarus, sociorum vectigalis ferrariarum servus (CIL XIV, Suppl., 4326; 102-117 AD).

[28] CIL XIV Suppl., 4570. Meiggs 1973, 333.

[29] G. Henzen, BdI 1875, 10-12; Houston 1980, 161 and note 39; Caldelli 2014, 74 and note 66. A pugillator is a letter carrier in Sidonius Apollinaris, Epistulae IX,14.

[30] CIL VI, 8583.

[31] Bruun 2002, 169-192. Many stamps were found in the area of the Piazzale delle Corporazioni, but the distribution is skewed, because here Vaglieri’s assistent Finelli investigated the underground water system with almost boyish enthusiasm, documented in the excavation diaries.

[32] Some of the pipes were found near Tor Boacciana. The outstanding works of art found here make this a possible location for the Ostian Imperial palace, documented in an inscription (CIL XIV, 66).

[33] CIL VI, 1224, CIL XIV, 172, CIL XIV Suppl., 5345 and 5384.

[34] An overview of the military presence in the harbours: Fourneau 2017.

[35] CIL XIV, 125 from 224 AD, from Portus: locus adsignatus ab Agricola Aug. lib. procurator Portus Utrisuque et Petronio Maxsimo centurio annonae et Fabio Maronae centurio operum. See also AE 1977, 171, from Portus (centurio frumentarius).

[36] CIL XIV Suppl., 4494.

[37] Cassius Ligus is documented as praepositus vexillationis in Ostia and made a dedication to Hercules in Portus (CIL XIV, 13; CIL XIV Suppl., 4380).

[38] We may assume that a ship was always in readiness for the governors and the Imperial family ("Seaforce One"). It may have docked in the Darsena, a narrow but deep part of the harbour of Portus. Cf. C. Roncaglia, "Claudius’s Houseboat", Greece and Rome 66,1 (2019), 61-70.

[39] The ancient name may have been Forum Ostiense.

[40] Cébeillac-Gervasoni - Morelli 2014, 11.

[41] On Imperial properties in the area see M. Maiuro, Res Caesaris. Ricerche sulla proprietà imperiale nel Principato, Bari 2012, 262-266.

[42] Suetonius, Claudius 38 and 40; translation Robert Graves and Michael Grant.

[43] CIL XIV, 95.

[44] Meiggs 1973, 62.

[45] CIL XIV Suppl., 4449 (Thylander B336: 337-345 AD).

[46] Meiggs 1973, 88. The argument is tricky, as Meiggs noted: "Civil and ecclesiastical administration did not always coincide".

[47] In Portus to the aerarium populi Romani / aerarium Saturni: Thylander A40 (Hadrianic), A41 (third century), A245 (late third century), A262 (third century), A328 (second century); CIL XIV, 667 (late second - first half of the third century), 1153 (second half of first- second century, reused), 1828 (third century), 1828a (third century? second half of the fourth - fifth century?); CIL XIV Suppl., 4821 (Hadrianic), 5037 (Hadrianic). In Ostia to the res publica Ostiensium, for example CIL XIV 166, 307, and 850. Thylander A19 stipulates that the fine is to be paid to the cultores Larum Portus Augusti.

[48] Meiggs 1973, 461. CIL XIV, 166 was found in Ostia in the Porta Romana necropolis.

[49] Naturalis Historia IX,14; XVI,202.

[50] De institutione oratoria II,21,18; III,8,16.

[51] CIL XIV, 163. This Claudius Optatus has been identified with the Optatus who was commander of the fleet at Misenum mentioned by Plinius, Naturalis Historia IX,62 (Meiggs 1973, 299), but that is not possible in view of the name (Bruun 2002, note 14).

[52] CIL XIV, 298.

[53] Scholium at Juvenalis XII,75.

[54] Metamorphoses XI, 26, 2.

[55] The old name might be preserved in CIL XIV Suppl., 4342, found in Portus. It is a dedication to Trajan from 101-102 AD, perhaps with the words [portum c]oloniae Osti[ensium restauravit].

[56] CIL XIV, 90: a dedication to Trajan from 112-117 AD, mentioning [port]us Traiani felicis. Meiggs 1973, 162.

[57] CIL XIV, 170, 408. Meiggs 87-88. Thylander B358, fragmentary, preserves only [port]us Trai[ani].

[58] CIL XIV, 47. Meiggs 1973, 510.

[59] Malaise 1972, 66-87; Bricault 2005, 580-592. Doubts about Portus as origin were already expressed by Floriani Squarciapino (1962, 25).

[60] Thylander A92, A295; CIL XIV, 408.

[61] Fragmenta Vaticana 148.

[62] CIL XIV, 16 (a dedication to Septimius Severus from 193-211 AD; C. Sentius Portesis); CIL XIV, 256 (album of the fabri navales; Portensis (line 4) and Anneus Portesius (plebs, line 355)); CIL XIV, 1422 (Octavia Portesia); CIL XIV Suppl., 4583 (found in Ostia, Casa di Diana; Aurelius Portesis). Ostiensis: not documented in Thylander.

[63] CIL XIV, 160, 430; AE 1989, 124; AE 1974, 123bis = EDR075655.

[64] CIL XIV, 318. See the section on the Forum Vinarium for the problematic AE 1974, 123bis = EDR075655.

[65] CIL XIV, 154, 172, 289, 309, 363, 364, 438; CIL XIV Suppl., 4140, 4452; Bloch 1953, nr. 29 and nr. 62; AE 2009, 192.

[66] AE 1982, 131.

[67] CIL XIV, 250, 251, 252, 341, 352; CIL XIV Suppl., 4144; Bloch 1953, nr. 42.

[68] CIL XIV, 101 (dedication to Marcus Aurelius), 374. The corpus also in CIL XIV, 4234 (from Tivoli), CIL XIV Suppl., 4359 (from Ostia), 4452 (from Ostia), 4676 (from Ostia), AE 1996, 309 (from Ostia; corpus pistorum, perhaps referring to the corpus in Rome). Fragmenta Vaticana 234 (pistores Ostienses). Cf. Codex Theodosianus 14.19.1. A possible freedman of the corpus in the Isola Sacra necropolis: CIL XIV Suppl., 4975.

[69] On the Piazzale delle Corporazioni.

[70] CIL XIV, 10.

[71] Bloch 1953, nr. 31 and CIL XIV, 169: corpus fabrum navalium Ostiensium patrono optimo, tribuno fabrum navalium Portensium. The first was set up by the ordinary members (plebes) of the Ostian guild. It was found in the Tempio dei Fabri Navales (III,II,1-2). The second, almost identical to the first, was set up by the entire Ostian guild. The place of discovery of this one is reported both as Ostia and as Portus.

[72] CIL XIV, 424: fragmentary, containing [cor]PVS FABRV[m] and [s]CHOLAM[---] (undated). Torlonia collection.

[73] CIL XIV, 256. See also Bloch 1953, 285 and Solin 1978. Late second or early third century AD. The locality is missing, but Portus is now generally accepted.

[74] Other inscriptions mentioning the fabri navales are:

- CIL XIV, 168 (from Ostia, a dedication by the fabri navales Ostienses to C. Iulius Philippus, without further qualifications; also dated April 11 195 AD).

- CIL XIV, 292 (in Pisa; a patronus fabrum navalium Ostiensium).

- CIL XIV, 368 (place of discovery unknown, a quinquennalis of the fabri navales Ostienses).

- CIL XIV, 372 (from Ostia; a quinquennalis perpetuus of the fabri navales Ostienses).

- CIL XIV, 456 (from Portus, q(uin)q(uennales) c(orpus) f(abrum) nav(alium) and a relief of a cargo ship).

- CIL XIV Suppl., 4656 (place of discovery unknown, perhaps mentions the fabri navales Ostienses).

- AE 1983, 118 (from the Basilica of Saint Hippolytus on the Isola Sacra, seems to mention a tribunus of the corpus fabrum navalium Portensium).

- AE 1989, 124 (from Ostia; a corporatus inter fabros navales).

- AE 1988, 196 (cf. AE 1932, 8 and CIL XIV, 321, the latter one found in Ostia; P. Celerius Amandus must have been linked to the fabri navales in view of a relief accompanying the inscription).

- Bloch 1953, nr. 43 (from Ostia, almost certainly of the fabri navales).

- A funerary inscription of a quinquennalis fabrum navalium in a private collection: Xavier-Loriot 2009 and Tran - Xavier-Loriot 2009.

[76] Konen 2001.

[77] Liber Pontificalis I, 183-184. Eodem tempore fecit Constantinus Augustus basilicam in civitate Hostia, iuxta portum urbis Romae, beatorum apostolorum Petri et Pauli et Iohannis Baptistae; insulam quae dicitur Assis, quod est inter Portum et Hostia.

[78] Codex Theosianus 13.5.4 (324 AD), 14.22.1 (364 AD), 14.15.2 (366 AD), 13.5.38 (414 AD).

[79] Cosmographia, Riese, Geographi Latini minores, p. 83. Tiberis ... facit inter portum urbis et Ostiam civitatem, ubi populus Romanus cum urbis praefecto vel consule Castorum celebrandorum causa egreditur sollemnitate iocunda.

[80] Epistulae 66,11 and 77,10.

[81] Chronicon, 474 AD.

[82] McCann 1978, 138-140. Inv. nr. 48.76.1. IG XIV, 943. Translation G. Downey.

[83] CIL XIV, 1828a documents a fine to be paid in Portus to the aerarium populi Romani in late antiquity. The date is not entirely certain however, see the comment in the CIL.

[84] CIL XIV, 133. Meiggs 1973, 165.

[85] CIL XIV, 140 (Fl. Alexander Cresconius). Meiggs 1973, 169.

[86] CIL XIV, 666 (Aur. Rutilius Caecilianus).

[87] CIL XIV Supplement, p. 612 note 48.

[88] K. Tabata, "The date and setting of the Constantinian inscription of Hispellum (CIL XI, 5265 = ILS 705)", Studi Classici e Orientali 45 (1997), 369-410.

[89] Is there a link with the Via Flavia on the Isola Sacra? As to the ordo et populus, cf. an echo in Ostia in the years 307-310 AD: the epigraphical "resurfacing" after half a century of the ordo et populus Ostiensium (EDR072926).