The excavations by Rodolfo Lanciani

The first excavations of the barracks of the fire brigade in Ostia (Caserma dei Vigili) were carried out by Rodolfo Lanciani. His activities in Ostia are documented for the first time in the Notizie degli Scavi of 1877. He was working then to the south of the museum. In 1880 and 1881 he was active in the theatre and on the Piazzale delle Corporazioni, close to the barracks. The barracks are mentioned by him for the first time, very briefly, in the Notizie degli Scavi of April 1888, and again in December. Excavations had taken place in the west part. A marble pedestal had been found in one of the rooms, with iron pegs embedded in lead to hold a statue, and with an inscription (the inscriptions will be discussed separately).[1] Furthermore part of a marble slab was found, one of many fragments to be found eventually, both in a room of the building and around the building.[2] Both the architecture and the two inscriptions led Lanciani to the identification of the building.

|

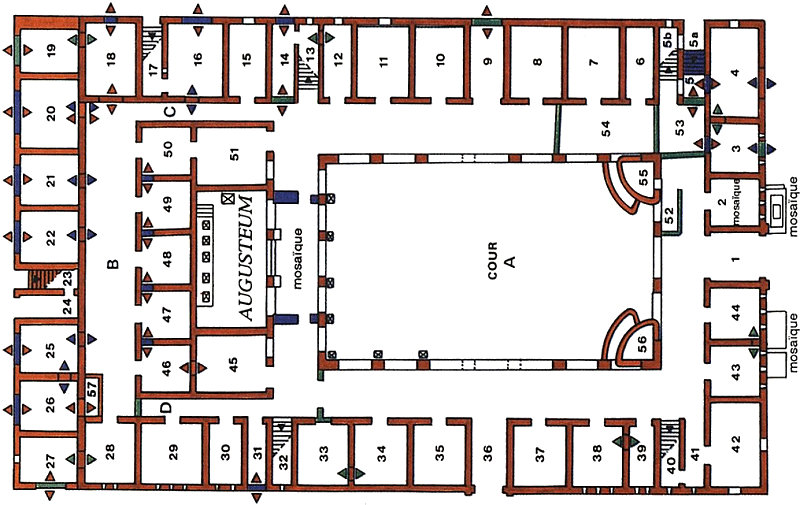

| Plan of the barracks with preferred room numbers. |

Further work is described in the Notizie degli Scavi of 1889. Lanciani believes that a Hadrianic domus with shops had been converted to barracks in the Severan period. A small room below a staircase (today numbered 31), receiving light through a narrow window, is identified as a prison. Graffiti were seen on the vault. Graffiti were also read on the facade, made directly on the bricks of the pilasters decorating the entrances of the long sides. Coins were found ranging from the reign of Gallienus (253-268 AD) to that of Julianus (355-363 AD), most of them dated to the reigns of Maxentius and Constantine. In the earth covering the ruins a French coin was found from the first half of the 17th century (earlier, in a room next to the corridor leading to the orchestra of the theatre, Lanciani's workers had found forty corpses, apparently of soldiers from the 16th century). On the street remains were found of the brick pilasters and tympanums that once decorated the entrances. Near one of the entrances a marble slab was found ending in a tympanum, with the depiction of an eagle on the tympanum and an inscription flanked by columns, mentioning Commodus.[3]

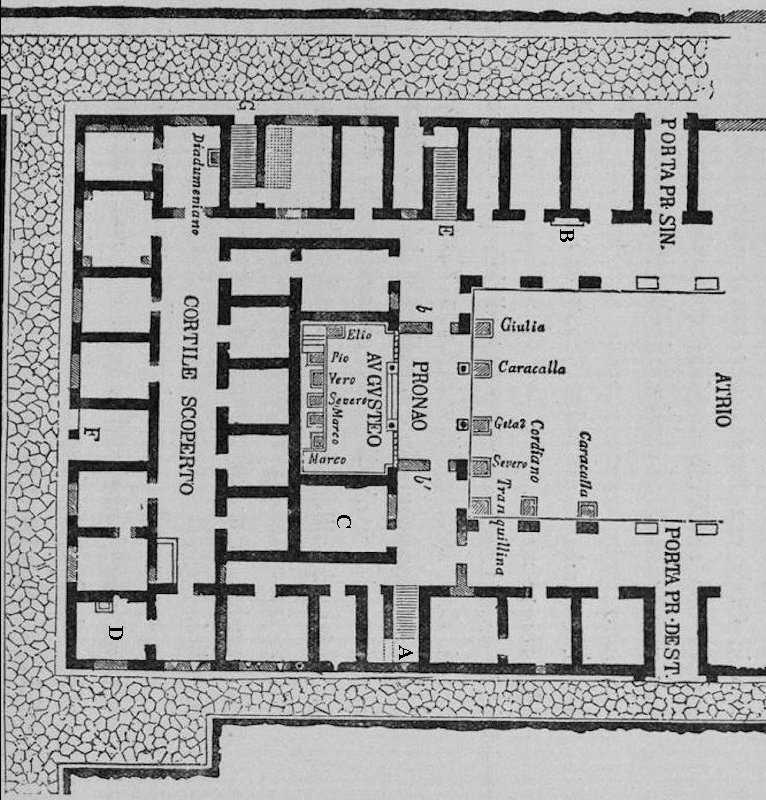

The two rooms that would become known as the Augusteum, a shrine of the Imperial cult, were unearthed. The walls of the Augusteum were decorated with various kinds of marble up to 2 meters, higher up with plaster. A podium at the back too was decorated with marble. The upper part of the back wall had collapsed inward. The famous mosaic depicting the sacrifice of a bull was found. In and near the Augusteum many inscribed marble pedestals were encountered: placed against brick piers and marble columns, in a corner of the courtyard, and on top of the podium. They looked like new. Traces of the red mineral minium were seen in the letters. One of those standing on the ground was found fallen over, covered by a layer of debris 0.40 high, on top of which was collapsed masonry. One had fallen down from the podium, another on top of a little staircase leading to the podium. Near the entrance of the Augusteum a tiny marble base (h. 0.12) was found with an inscription.[4] Two fragments of inscribed slabs emerged.[5] On the plinths of the bases supporting the marble columns the letters P D E, but upside down, were read.[6] One marble column was complete, of the other only the lower part and travertine base remained. A marble altar without inscription was found. In front of the podium the foundation of an altar was seen of which no traces remain, says Lanciani.

The Augusteum after the excavation. NSc 1889, figure on p. 74.

Lamps were found of Annius Serapiodorus, and coins ranging from Aurelianus to Constantine, and from Commodus to Constantius. As to sculpture: a marble portrait bust of a man with a beard (not an Emperor) emerged in the most south-western room (room 27),[7] and elsewhere a fragment of a bronze statue. The walls of the rooms of the barracks were decorated with plaster, thick cocciopesto on the lower part, thin plaster on the upper part, later covered with whitewash. The facade was never plastered.

The west half of the barracks, after the 1888-1889 excavations. NSc 1889, figure on p. 78.

Thin inscribed slabs were found, to be inserted in shallow recesses in the walls, such as nr. B on Lanciani's plan. Similar texts, but painted, were also found on the west wall of room 45, to the south of the Augusteum (black on white, white on red, red on yellow, and so on). One text, disappeared, was in a tabula ansata (0.80 x 0.46). On fallen plaster in the room, five fragments of such texts were found.[8] Many graffiti were found on the facade and in the interior, on bricks and on plaster (the painted texts and graffiti will be discussed separately).

In a short account about the excavation, published in France, Lanciani wrote:

"Although we are dealing with the first excavation, we were not able to discover in the entire building a single fragment of the Imperial statues to which divine honors had been rendered in the Augusteum. The altar itself was not only knocked down or taken away before the site was finally abandoned, but traces of its base, which was of masonry, were even carefully removed by leveling it with the pavement. If the pedestals have been respected, it is because their inscriptions, purely historical, did not contain anything offending the Christians.

One circumstance to note is the complete disappearance of all the architectural marbles that could be easily removed, door and window thresholds, staircase steps, wall plinths etc. This circumstance proves, in my opinion, that the solidly built barracks withstood ruin for many years, even centuries, and that the unfortunate survivors of the disasters of the fifth century had the leisure to rob everything bit by bit, by burning all the marbles in the lime kilns.

I noticed the absolute lack of roofing materials among the rubble. I deduce the consequence that the roofs sagged by decay and by the rotting of the carpentry, long before the walls fell. One had plenty of time to take the materials away. The collapse of the walls of the first floor, where the dormitories and officers' quarters were located, occurred when the lower floor at atrium level and the atrium itself were already covered with a layer of debris a meter or a meter and a half thick. The layer is made up, in large part, of materials (mud and sand) deposited by the Tiber, following flooding.

One of the beautiful portasanta columns that decorated the pronaos of the Augusteum was lying with the bottom of the shaft at the height of Caracalla's pedestal, and the top at 1m.35 above the pavement. The falling of the walls took place from west to east: the shock was so violent that several pedestals fell in the same direction, although they were not directly hit by the falling masses."

In 1889 the complete outline of the building had been recognized, but the part to the east of the entrances in the long sides would remain unexcavated, also therefore the main entrance (room 1). By now an "island" had been excavated: the Four Temples, House of Apuleius and Mithraeum of the Seven Spheres, the theatre and a tiny part of the Square of the Corporations, a small part of the Baths of Neptune and the west half of the barracks.

Reconstruction drawing of the west part of the barracks.

Drawing: Parco Archeologico di Ostia.

The excavations by Dante Vaglieri

The excavations were resumed in 1911 by Dante Vaglieri, and described once again in the Notizie degli Scavi. One of his collaborators was the famous architect Italo Gismondi. Below is a simplified summary of the published reports. For further details the excavation diaries (Giornale degli Scavi), written by Raffaele Finelli, may be consulted in the offices of the Parco Archeologico di Ostia (non vidi).

The excavations of Via della Fullonica to the north of the barracks, in 1913.

In the centre is architect Italo Gismondi. Photo: Parco Archeologico di Ostia.

The east half was now investigated. The first room to be excavated was in the south-east corner (room 42). It turned out to be a large latrine. In the room an inscribed marble altar was found with a dedication by one of the vigiles to Fortuna Sancta. In the wall next to the entrance, still in the interior, the supports had been preserved of a hanging aedicula, of which a marble capital and the tympanum were found on the ground. The tympanum carried the inscription FORTVNAE SANCT(ae).[9] Among the finds were a part of a mirror, a key, a lock and some coins.

Reconstruction drawing of the latrine with the aedicula.

Drawing: Parco Archeologico di Ostia.

In unspecified rooms fragments of inscriptions were found,[10] and a mould for metal tesserae with the letter F. In the room to the south of the main entrance (44) were remains of plaster, and, in the south wall, a rectangular depression (0.40 x 0.67) and a shallow arched niche (0.40 x 0.19 x 0.08). Near a secondary door in this wall were the remains of a painted text, red on white.[11] On the plaster were further traces of red letters and regular graffiti (concentric circles, numbers, letters). In the back wall were two further depressions (0.43 x 0.30; 0.33 x 0.54), one with remains of white and red plaster. In the same wall, in a partially preserved tabula ansata, was a long text, black on white.[12] On the north wall were more graffiti of concentric circles and numbers, and a painted tabula ansata (0.60 x 0.28) with eight lines of text that could not be deciphered. On fallen plaster two more painted texts were seen, black on white and white on black,[13] and a graffito.[14] Some oil lamps were found, and a few objects of bronze (a fibula, nails) and bone (decoration of furniture, needles). In the room to the south (43) a painted text (black letters) was found on the north wall.[15] In the north-east corner of the building (room 4) a structure looking like an oven was unearthed, next to which were burned bones.

Remains of an oven in the north-east corner of the building.

NSc 1911, p. 370 fig. 1.

On the east side of the courtyard two curved water reservoirs were found, with curved basins in front. Vaglieri interprets these as drinking troughs for animals. On an unspecified spot a small inscribed slab of marble was found.[16] Among the other finds were an antefix and a few pieces of sculpture: a relief with on one side the head of a satyr, on the other a mask with a club; a base with two tree trunks, a lion skin and lion paws. Again on unspecified spots pieces of marble slabs were found that had been reused as hinges for doors or windows.[17] Vaglieri believes that the reuse took place in the Severan period, because the slabs all belong to the second half of the second century.

The excavation was completed in 1912. Additional walls in the north-east part lead Vaglieri to the conclusion that a habitation was installed here (rooms 52-54). In this part of the north porticus a large amphora without neck was embedded in the earth. In the porticus a small latrine was installed when the habitation was created. In the room to the north of the vestibule (2) was a black-and-white geometric mosaic. On the south and east wall of the room were paintings of red and yellow compartments, created with oblique lines, between painted columns. In the central compartments were human figures, on the south wall a naked male figure with a raised right arm. In the other compartments were branches with flowers. On the back wall a graffito was seen, probably with a date. The travertine threshold of the narrow room 6 had suffered from a fire. In room 7 four travertine consoles were found, fallen down from the upper floors. Finds from this area were a vessel of green glass with a medallion showing a putto and a harness, two lead tesserae, one of which with on one side the letters CVR and on the other M[---].

Paintings on the east wall of room 2.

Photo: Fornari 1913, Tav. XXXV.

Paintings on the south wall of room 2.

Photo: Fornari 1913, Tav. XXXV.

The floor of the three entrance vestibules and of the courtyard was made of bipedales. Many graffiti were seen on the pilasters decorating the eastern entrance porch. Traces of graffiti were also seen on the plaster of the south wall of that vestibule. The room had been filled with a large quantity of rubbish before the vault collapsed. The north part of the east porticus had a black-and-white mosaic. Room 3 had a floor of opus spicatum and painted walls. The same kind of pavement was found in room 33 on the south side. The west and north wall of room 33 had paintings of yellow compartments with black bands on the lower part, and red and white bands on the upper part. On the west wall was a graffito of a boat. In the same room a fragment of a marble cornice was found with the letters KAEOPƆB, inscribed roughly.[18] Among the finds in the area were: a bone tessera with the text MTO,[19] and, made of bronze, a handle of a vessel with a depiction of Minerva wearing a helmet, a weight of 120 grams, a ring with the text XV,[20] and a key. Painted vaults had fallen on the street.

In understairs 5 two tombs were found. In one of these a tabula lusoria had been reused.[21] Also in one of the tombs a folded tabula defixionis was found, closed with a nail. It was not possible to open and preserve it. Room 31 on the south side had a secondary entrance from the street. To the left were graffiti, of which only AVRELIVS HERMOGENES is mentioned. In front of the door was a travertine step and to the right of that a bench, 0.30 high and 3.00 long. In most of the rooms excavated by Vaglieri was no building material from the upper floors, which had apparently been removed at some point in time in the past. Room 18 had also been a large latrine.

On the street, the east entrance was flanked by black-and-white mosaics, two with a depiction of a crater, one with a Greek text, one with a Latin text. In the facade of the barracks above the mosaics were holes in which the beams had been inserted that supported the roof of little rooms set against the facade and containing the mosaics. Three fragments of relevant inscriptions were found on Via della Fullonica.[22] Still in 1912 a detailed plan of the entire building was published.[23] Later in the year relevant fragments of inscriptions were found on Via dei Vigili,[24] and to the north of the barracks.[25] Fragments of painted texts, according to Vaglieri from an upper floor, were found on Via della Fullonica.[26]

A photo of the east part of the barracks, seen from the west, taken by Thomas Ashby, perhaps in 1912.

Photo: British School at Rome.

Dating the building and the excavations by Fauto Zevi

During the excavation many brick stamps were recorded by Lanciani and Vaglieri, and these were studied by Herbert Bloch in 1938. Domitianic stamps belong to the drainage system in this area. The building contains many Hadrianic brick stamps, a series identical to that of the adjacent Baths of Neptune: the two buildings were built with the same material, at the same time. Most likely insula VI to the west and insula III to the east may be added. The barracks must have been inaugurated in 137 AD at the latest, in view of an inscription in honour of Lucius Aelius Caesar of that year in the Augusteum. The stamps point to the period 132-137 AD.

The mosaic of the Augusteum was installed in a pronaos or vestibule, in the west part of the porticus of the courtyard. Two lateral walls were added in the porticus. In between two marble columns were placed. This intervention has been dated to the Severan period, 203-207 AD as can be deduced from more brick stamps and inscriptions. The mosaic has stylistically been dated to the same period by Giovanni Becatti. In 1964 the mosaic was detached and fixed on a modern support. Fausto Zevi used this opportunity to investigate the lower levels, the results of which were published once again in the Notizie degli Scavi.

Zevi was able to confirm some observations by Vaglieri: there was an older building below the Hadrianic barracks, completely razed to the ground. It could be dated to the end of the reign of Domitianus, 90-96 AD. In the old building dedications were placed by the vigiles to Traianus, between 102 and 116 AD, and Hadrianus, between 119 and 127 AD. Fragments of these inscribed marble slabs were found by Zevi below the mosaic.

Notes

[1] CIL XIV Suppl., 4393; EDR106390; 217 AD.

[2] Also in a drain below a road and near the Piccolo Mercato. CIL XIV Suppl., 4389 - 4493 - 4681; EDR106387; 212-214 AD.

[3] Later more fragments would be found in a lime kiln on Via della Fontana, directly to the west of the barracks. CIL XIV Suppl., 4378; Calza in NSc 1927, 392; AE 1928, 125; EDR106370; 190 AD.

[4] CIL XIV Suppl., 4552; EDR004987.

[5] CIL XIV Suppl., 4508; EDR106803 and CIL XIV, Suppl., 4396; EDR106393.

[6] CIL XIV Suppl., 5249a; EDR109948. CIL XIV Suppl., 5249b; EDR109949. Cf. CIL XIV Suppl., 5250.

[7] Not in SO V, IX or XVII. A candidate is inv. nr. 261, Arachne 56460.

[8] CIL XIV Suppl., 4513; EDR106815.

[9] The altar: CIL XIV Suppl., 4281; EDR072480. The tympanum: CIL XIV Suppl., 4282; EDR072481.

[10] A further fragment of CIL XIV Suppl., 4378. CIL XIV Suppl., 4501; EDR072502. CIL XIV Suppl., 4502; EDR072539. CIL XIV Suppl., 4490; EDR072503.

[11] CIL XIV Suppl., 4516; EDR106822.

[12] CIL XIV Suppl., 4510; EDR106810.

[13] CIL XIV Suppl., 4511; EDR106812. CIL XIV Suppl., 4514; EDR106817.

[14] CIL XIV Suppl., 4518; EDR106828.

[15] CIL XIV Suppl., 4509; EDR072504.

[16] CIL XIV Suppl., 4499; EDR072528.

[17] CIL XIV Suppl., 4500; EDR072537. CIL XIV Suppl., 4502; EDR072539. CIL XIV Suppl., 4503; EDR072538. CIL XIV Suppl., 4506; EDR106798.

[18] CIL XIV Suppl., 5254; EDR109955.

[19] CIL XIV Suppl., 5318,2; EDR110100.

[20] CiL XIV Suppl., 5313,2; EDR110084.

[21] CIL XIV Suppl., 5317,3; EDR110098.

[22] CIL XIV Suppl. 4502; EDR072539.

[23] NSc 1912, 164, fig. 5.

[24] CIL XIV Suppl., 4504; EDR106795. One fragment had already been found near the barracks in 1897.

[25] CIL XIV Suppl., 4385; EDR106375. CIL XIV Suppl., 4507; EDR106802.

[26] CIL XIV Suppl., 4515; EDR106820.