Rome had two main commercial harbours in Italy: Puteoli, modern Pozzuoli on the Bay of Naples, and Ostia-Portus. Looking now at Puteoli from the perspective of Ostia-Portus, we may begin by quoting Ostia's great historian Russell Meiggs.

Writing about the Republican period, Meiggs says: "Puteoli, with its well-sheltered harbour and long association with Greek traders, controlled the larger part of Rome's eastern trade, and became the main distributing centre for the luxuries that Italy drew from the Hellenistic world; but there is no evidence and little probability that Puteoli also monopolized the trade with Spain, Gaul and Sardinia." Nevertheless, "Strabo, after cataloguing the rich resources of Roman Baetica, emphasizes the volume of exports carried in large merchantmen 'to Puteoli and Ostia, Rome's harbour'; in number, he says, they almost matched the shipping from Africa."

The abundance of the exports of Turdetania [southern Spain] is indicated by the size and the number of the ships; for merchantmen of the greatest size sail from this country to Dicaearchia [Puteoli], and to Ostia, the seaport of Rome; and their number very nearly rivals that of the Libyan ships. Strabo, Geography III,2,6. Translation H.L. Jones. Meiggs then adds: "Spanish and African goods carried to Puteoli were not intended for the Roman market, but for distribution in thickly populated Campania and the south of Italy. Western goods exported to Rome came through Ostia. The distribution of Sicilian exports in Italy is less clear but it is probable that Puteoli secured the greater part of the trade. Even goods intended for Rome seem to have been unloaded at Puteoli. The harbour was better, the Greek background more congenial, and the dominance of corn ships in the restricted river harbour at Ostia probably made it difficult for other ships to unload their cargoes quickly. Though transport by land was considerably more expensive than by water such products as papyrus, glass, and linen from Egypt, sculpture and jewellery from Sicily, were probably carried by the Via Appia to Rome. Bulk supplies of corn, however, were different. Unless secure evidence is found to the contrary we should assume that the corn from Sicily as well as from Africa and Sardinia came to Rome through Ostia."

However, the grain for Rome was not imported from Africa, Sicily and Sardinia alone. Egypt contributed as well, using a grain fleet stationed at Alexandria. Meiggs continues: "But all was not well with Ostia. When Egypt was annexed after the battle of Actium, the Alexandrian corn ships did not come to the Tiber. Augustus knew the value of Egypt. He hoped that by expanding corn production in the Delta he could eliminate the recurring corn crises that had increased political instability at Rome when rival dynasts were competing for power. In the Republic Rome had relied primarily on Sicily and the western provinces; Egypt's contribution was probably unimportant. Augustus set the army in Egypt to revitalize the long-neglected irrigation system. Before he died, if we can believe a late authority, 20 million modii, more than six times the tithe from Sicily, had been added to Rome's annual supply."

The region of Egypt, difficult to enter because of the inundation of the Nile and impassable because of swamps, he [Augustus] made into a form of province. By the labor of soldiers, he opened canals, which through neglect had been clogged with the slime of ages, to make Egypt a bountiful supplier of the city's ration. In his time, twenty million allotments of grain were imported annually from Egypt to the city. Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus I,4-6. Translation T.M. Banchich. Meiggs continues: "But the Alexandrian corn fleet ended its journey at Puteoli and not at Ostia. The river harbour was probably already dangerously overcrowded. More important, large ships could not enter the river mouth without transferring part of their cargoes to tenders at sea. The Alexandrian corn transports were among the largest merchantmen afloat; the risk could not be taken, and they unloaded their cargoes at Puteoli, whose excellent harbour facilities were already well known to Alexandrian traders. New granaries must have been built to store the Egyptian corn until it could be moved to Rome. It is possible that some of this corn was carried by mules along the Via Appia. It is more likely that is was reloaded into smaller vessels to complete the journey by water."

He then moves on to the impact of the building of the harbours of Portus. "It is generally assumed that Claudius hoped, by providing a larger and safer harbour at Ostia, to make Rome independent of Puteoli. If this was his intention it was not realized. Seneca, in a letter written between 63 and 65, describes the scene of general excitement on the sea front at Puteoli when the Alexandrian corn fleet is signalled. He implies that this is the end of their voyage, and that it is a regular event in the town's life. Similarly when Statius' friend, Maecius Celer, sets out for his legionary command in the east he sails on an Alexandrian corn ship from Puteoli and not from Ostia. St. Paul, appealing as a Roman citizen to the emperor, lands at Puteoli, as does Titus returning to his Jewish triumph. Mucianus reported that he had seen elephants walking backwards down the gangway from their ship at Puteoli because they were terrified of the distance from the shore; the elephants were probably bound for Rome. The evidence of Pliny the elder, writing under Vespasian, points the same way. In recording fast sailing times he quotes voyages from Spain, Gaul, and Africa to Ostia; Alexandria is linked with Puteoli. The continued attention paid by Emperors to Puteoli confirms the impression drawn from these scattered sources. Claudius sent an urban cohort to Puteoli as well as to Ostia to act as a fire service; the reason is surely that Roman corn from Egypt was stored in the town. Domitian's rebuilding of the branch road that left the Via Appia near Sinuessa and rejoined it at Puteoli, cutting out the detour through Capua, implies that speed of travel between Puteoli and Rome was still important."

Click on the image to enlarge.

From Ostia to Puteoli. Samuel Butler's atlas, 1907."Claudius was not intending to divert shipping from Puteoli; his main concern was to provide security for the corn from Africa, Sicily, Sardinia and the western provinces. There remained the problem of Egyptian supplies. The emperor Gaius is praised by Josephus for beginning the enlargement of the harbour at Rhegium for the benefit of the Alexandrian corn fleet; Claudius presumably completed the work. It provided shelter at a dangerous point on the voyage. But safe arrival at Puteoli was not the end of the matter. The Egyptian corn stored in Puteolan granaries had to be moved to Rome either by road or by sea. The quantity involved would have made land transport, by mule or wagon, extremely uneconomic; the sea route along the west coast, poorly provided with harbours, was dangerous."

"Trajan's work at Ostia had wider consequences. The increased harbour and the security of the inner basin made it possible to bring the large merchantmen of the Alexandrian corn fleet, which had hitherto docked at Puteoli, to Ostia. The earliest specific evidence that their Italian headquarters had been transferred comes from the end of the second century; but it is probable that the change of policy followed directly the completion of the new basin and that it was in fact one of Trajan's main motives in undertaking the work. Henceforward Ostia becomes the main reception port for merchantmen from the east as well as from the west."

The earliest specific evidence for the arrival of the Alexandrian fleet in Portus is a statue base in honour of Commodus with a Greek inscription, found in Portus. It was set up by the skippers of the Alexandrian transport fleet. A coin from the reign of Commodus depicts the harbour of Portus and a ship with Jupiter Serapis seated on the stern. There is probable evidence from the reign of Antoninus Pius: Alexandrian coins of his reign show Nile and Tiber clasping hands.

The coin of Commodus depicting Portus and a ship

carrying Jupiter Serapis (centre left).The coin of Antoninus Pius depicting Nile and Tiber

clasping hands (Dattari 1901, Tav. XX nr. 2782).Meiggs continues: "By attracting eastern shipping to Ostia the building of Trajan's harbour marked a decisive stage in the decline of Puteoli's importance and prosperity. A letter addressed to the senate of Tyre on 23 July A.D. 174 by the Tyrian traders at Puteoli gives a lively illustration of the change."

By the gods and by the fortune of our lord-emperor. As almost all of you know, of all the trading stations at Puteoli, ours, in adornment and size, is superior to the others. In former days the Tyrians living at Puteoli were responsible for its maintenance; they were numerous and rich. But now we are reduced to a small number, and, owing to the expenses that we have to meet for the sacrifices and the worship of our national gods, who have temples here, we have not the necessary resources to pay for the rent of the station, a sum of 100,000 denarii a year; especially now that the expenses of the festival of the sacrifice of bulls has been laid on us. We therefore beg you to be responsible for the payment of the annual rent of 100,000 denarii ... We also remind you that we receive no subscriptions from the ship owners or traders, in contrast to what happens with the station of the sovereign city of Rome. We therefore appeal to you and beg you to take thought of our fate and of the affair. "In the Republic Puteoli had been of first importance to the Tyrian trader, but his ships could now pass on to the imperial harbours, and the main station was transferred to Rome. Similarly in the second century an Egyptian recruit for the fleet bound for headquarters at Rome to report for duty and learn to what unit he was to be attached sails on to Trajan's harbour, where he finds a man to take a letter to his mother. A second letter tells us that he arrived in Rome on the same day."

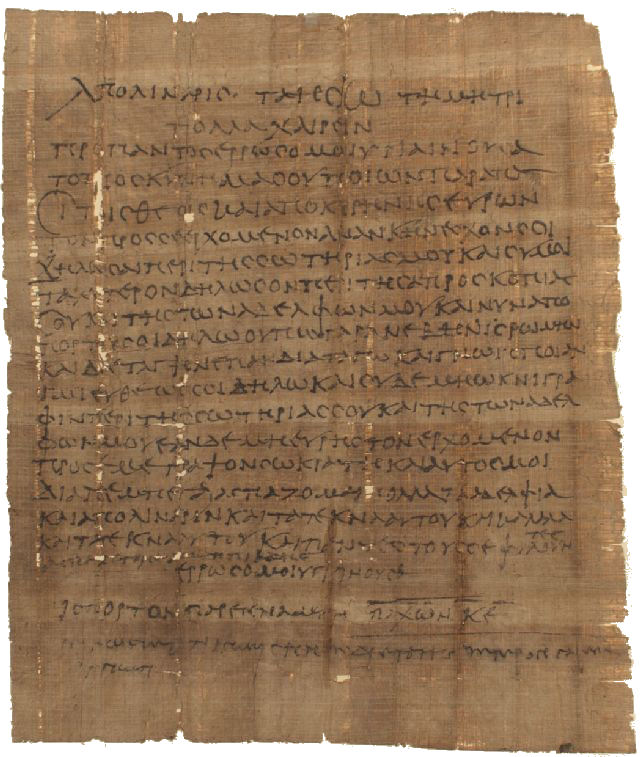

Apollinarius to Thaesion, his mother, many greetings.

Before all else I wish you good health and make obeisance on your behalf to all the gods.

From Cyrene, where I found a man who was journeying to you,

I deemed it necessary to write to you about my welfare.

And do you inform me at once about your safety and that of my brothers.

And now I am writing you from Portus, for I have not yet gone up to Rome and been assigned.

When I have been assigned and know where I am going, I will let you know at once;

and for your part, do not delay to write about your health and that of my brothers.

If you do not find anybody coming to me, write to Sokrates and he forwards it to me.

I salute often my brothers, and Apollinarius and his children,

and Kalalas and his children, and all your friends. Asklepiades salutes you.

Farewell and good health. I arrived in Portus on Pachon 25 [May 20th].

(2nd hand) Know that I have been assigned to Misenum, for I learned it later.

(Verso) Deliver to Karanis, to Taesion, from Apollinarius, her son.

PMich 4527.Meiggs does add nuance to his argument. "But though the Alexandrian corn fleet no longer discharged at Puteoli, the storage capacity designed for Egyptian corn was still available and it was sound sense to use it. That Puteoli was still concerned with Rome's corn supply is clear from inscriptions. The finding of a dedication to the genius of the colony at Rusicade, an important export centre for African corn, is inconclusive, for the corn exports implied could have been for local distribution from Puteoli; but Puteoli's inscriptions include records of two junior officials in the Roman corn department, a paymaster and a clerk, and the paymaster's duties covered Ostia as well, disp(ensator) a fruminto Puteolis et Ostis; these men were concerned with Rome's corn. The natural inference is that Roman corn was still stored at Puteoli. There was a limit to the storage capacity that could be provided at Ostia, and it was a wise insurance against widespread fire to distribute Rome's reserves. But a secondary role in the provisioning of Rome was poor compensation for the loss of the greater part of Rome's eastern trade. When Ostia was at the height of her prosperity in the middle of the second century Puteoli was being supervised by curators imposed by the central government, a sure indication that the town's economy had lost its buoyancy."

As to the prosperity of Puteoli, Meiggs follows the communis opinio that was formulated for the first time by Charles Dubois in 1907. John D'Arms reviewed it critically in 1974. He points out that there is no conclusive evidence that the Alexandrian grain fleet was redirected to Portus during the reign of Trajan and that the presence of curatores rei publicae could also be explained by the wish to correct undesirable side effects of local affluence, such as illicit building projects. D'Arms points out that there are many general signs of wealth in Puteoli throughout the second century and well into the third. Economic deterioration is not seen and the indications of stagnation are first visible only in the late fourth century.

In 1974 much remained to be studied, and it has: there has been a steady flow of publications since then. Whereas in Pozzuoli we do not find an extensive excavated archaeological area such as that of Ostia, the objects that have emerged provide a wealth of information. In this section archaeological, epigraphical and literary evidence will be presented, focusing as much as possible on Puteoli, not on the towns to the west and east (Misenum - Baiae - Portus Iulius - Neapolis - Herculaneum - Pompeii - Stabiae).