The discussion of the Barracks of the Vigiles in the Topographical Dictionary is, as usual, concise. Therefore some issues are discussed here in more detail. Unfortunately the barracks have not been the subject of a monograph. There is no detailed catalogue of the building, not even extensive photographic documentation. We owe many observations about the masonry to John Rainbird (1986) and Robert Sablayrolles (1996), but the real work is still to be done. In the absence of a catalogue an analysis of the building phases will not be attempted here.

Castra and excubitoria

In the summary of the regionary catalogues excubitoria only are mentioned, the word castra is not used in relation to the vigiles. In the lists per region, Castra Praetoria and Castra Peregrina are mentioned, but for the vigiles only the presence of a cohort is noted. Similarly the Corpus Iuris Civilis juxtaposes people "belonging to the night watch, or serving in the city camps". This raises the question whether the vigiles lived in castra, in camps. Today soldiers live in barracks, while policemen, firefighters and the personnel of ambulances live in regular houses or apartments. That makes perfect sense if we remember that the latter are not primarily on duty for a single, major crisis, but can be active throughout the day for all sorts of incidents. There is no need for all of them to be available all the time. On the contrary: shifts need to be available, 24/7. The vigiles too may have lived in houses and apartments. The right to free grain may also be considered here. It makes no sense for soldiers living in barracks and receiving their meals there.[1]

Inscriptions do mention castra of the vigiles in Ostia and Portus. In two inscriptions from Ostia, from 207 AD, Septimius Severus and his son Caracalla are called restitutores castrorum. In a third inscription Iulia Domna, wife of Septimius, is called mater castrorum.[2] In an inscription from Portus, from the Severan period, the word castra has been preserved, so there was a camp there as well, of which only a few walls were found. This does not prove that there were castra in Rome as well. In Ostia detachments from Rome were active for periods of four months, so that the men needed temporary housing.

The duration of the stay in the harbours, four months, is surprisingly short. Knowledge of the city and fire hazards had to be built up time and again by each detachment. Perhaps centurions stayed in the harbours permanently, for continuity. What motivated this short period deserves further study. Perhaps it resulted from the intertwining of the pool of vigiles with the population of the city of Rome (in houses and apartments), as opposed to forming a separate entity (in a military camp). A longer stay in the harbours would take them away from their family for a long period of time.

The Augusteum

After Zevi's excavations in 1964 it was clear that three Augustea can be recognized. Augusteum I was installed in the Domitianic barracks. It contained dedications to Trajan and Hadrian (marble slabs). It was apparently on the spot of the later Augustea, but we know nothing about the appearance. Augusteum II was installed in the new barracks, erected at the end of Hadrian's reign. It consisted of a room to the west of the courtyard, presumably including the bench set against the back wall (the bench does not seem to have been dated explicitly). Some of its marble bases were reused in Augusteum III, identical to Augusteum II, but with an added vestibule and mosaic.

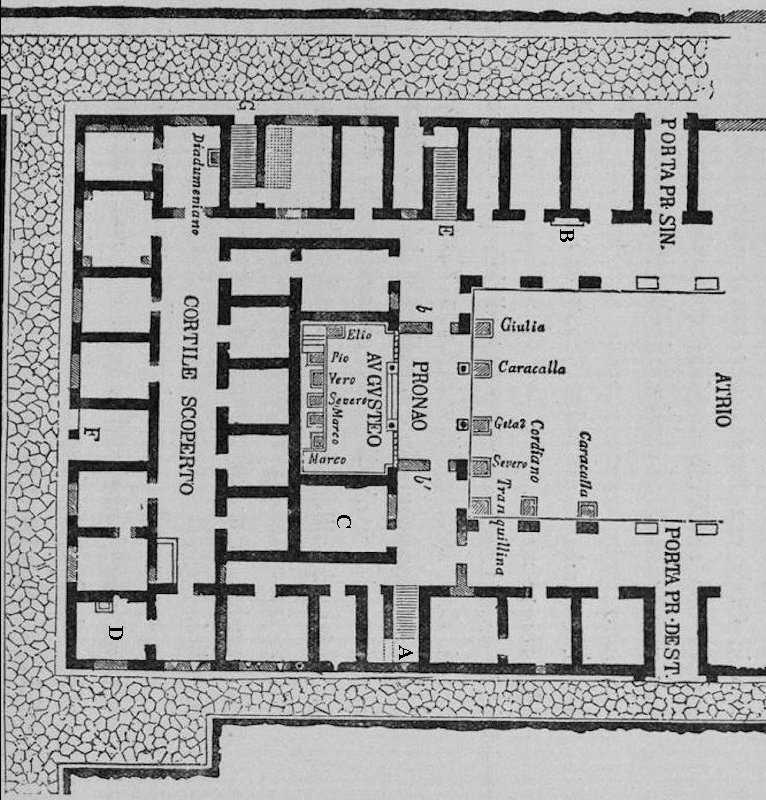

Reconstruction of the Augusteum. Plaque on the excavations.

The west half of the barracks, after the 1888-1889 excavations. NSc 1889, figure on p. 78.

In 2005 François-Dominique Deltenre drew our attention to the position and nature of the bases linked to Augusteum II and III. In 2018 Margaret Laird dealt with the subject in more detail. The oldest dedication from Augusteum II, and most likely the first, was for Lucius Aelius Caesar. He was adopted by Hadrian in 136 AD, but died already two years later, half a year before Hadrian died. It is a high base with holes in the top for the fastening of a statue. No base with a dedication for Hadrian has been preserved, but his name may have been on the tympanum above the entrance of the shrine.

The oldest base was found next to the wide bench against the back wall of the shrine. Five more bases were discovered at the foot of the bench. They are very low and therefore must have been placed on top of the bench. Three mention the dedicant: all seven cohorts of the vigiles. The oldest of these bases are quite similar: a dedication to Antoninus Pius from 138 AD and one to Marcus Aurelius from 140 or 145 AD. The next two bases belong to 162 AD. One has a dedication to an adoptive son of Antoninus Pius, Lucius Verus, the other was for Marcus Aurelius. On the upper rim of the latter base is a relief of sacrificial implements and bovine skulls (bucrania).

The latest base carries a dedication to Septimius Severus from 194-195 AD. An earlier inscription on this base was erased. It has been suggested that it was for Hadrian or Commodus. Laird however points out that the base is very similar to the base of Marcus from 162 AD, including the relief. She suggests that it was another dediction to Lucius Verus, this time forming a pair with his co-ruler Marcus Aurelius. These two bases with sacrifical objects have a round, roughly chiseled elevation on the top, but no holes for fastening a statue, contrary to the other bases. They have therefore been interpreted as altars, but are according to Laird merely symbolic altars. She also suggests that they supported hollow metal bases (around the elevations), carrying busts of precious metal.

|

| Artist's impression of the object that may have stood on top of the bases of Lucius Verus (?) and Marcus Aurelius. Image: Herz 1982, Abb. 1. |

Two more dedications may also come from Augusteum II and III, but these are on marble slabs, not on bases. The first is from 190 AD and was for the well-being of Commodus. The second is a dedication for the well-being and victory of Caracalla. Perhaps they were attached to the front of the bench or the back wall of the Augusteum.

The shrine of Anatellon

The dedication to Caracalla mentioned above speaks of an aedes, a shrine of some importance. The inscription has been placed in the years 212-214 AD, 214 with a question mark.[3] It was erected by Quintus Silvius Anatellon, beneficiarius of the Prefect of the Vigiles, with the authority of seven people, including Quintus Marcius Dioga, Prefect of the Vigiles, and Marcus Aurelius Valentinus, Subprefect of the Vigiles. In the last line is stated that Anatellon erected a shrine at his own expense: aedem de suo fecit. The last line has much smaller and shallower letters, and could well have been added later.

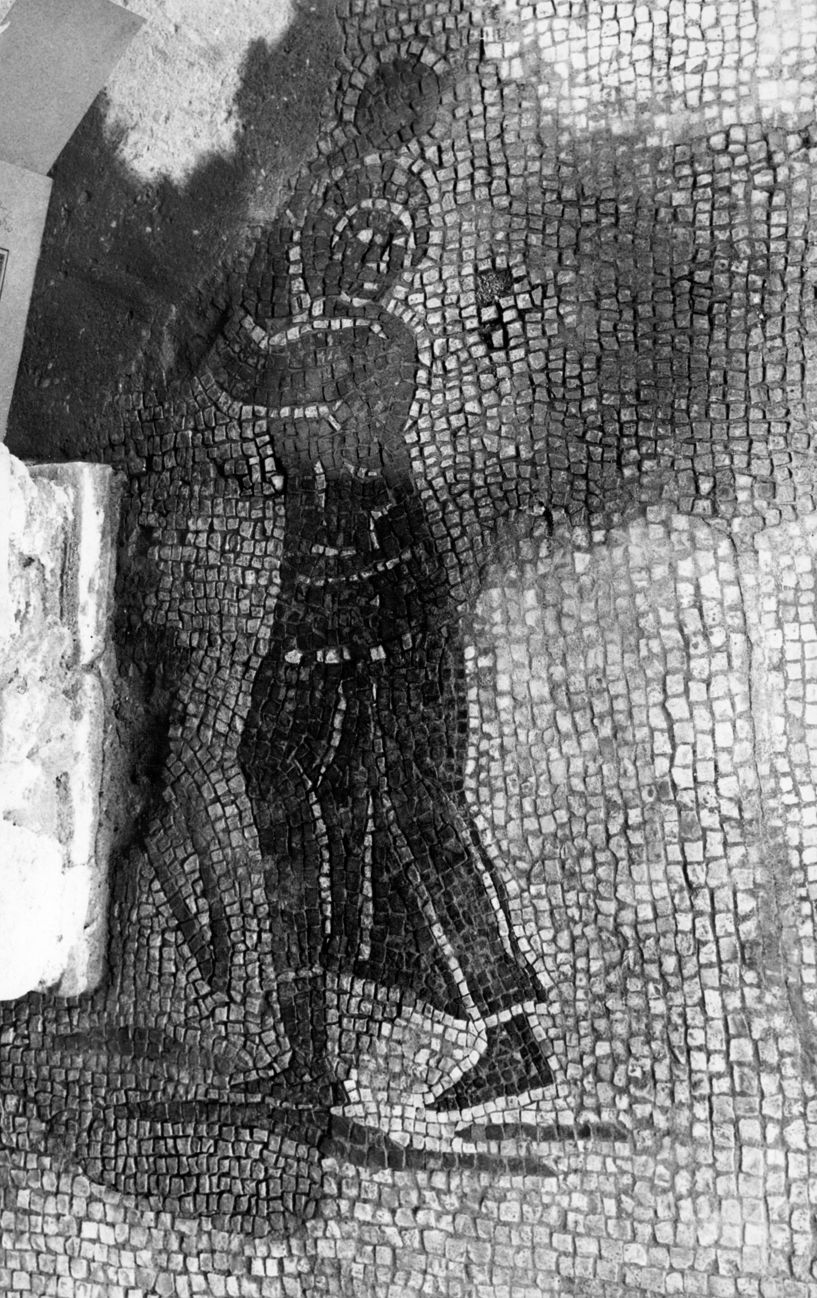

There is no trace of such a shrine in the barracks of the vigiles, which has led me to the idea that it was located elsewhere. A very attractive candidate is the Sacello del Silvano (I,III,2), a shrine tucked away in the Caseggiato dei Molini, a bakery (I,III,1). The shrine was extended and decorated in 214-215 AD. Caracalla featured prominently. Through a row of human figures he was compared to Augustus and Alexander the great, and thanked for his concern with the grain supply. Next to the painting of Silvanus that gave the shrine its name is a graffito written by Calpurnius, a sebaciarius from the vigiles. It contains an acclamation for Caracalla, and the consular date 215 AD. On the floor is a black-and-white mosaic with one isolated figure: a popa, an assistant at sacrifices, holding a hammer above his head. The figure is singularly out of place in the small shrine. It could be interpreted as a reference to the mosaic in the Augusteum, which shows a popa, a victimarius, and bulls.

|

|

|

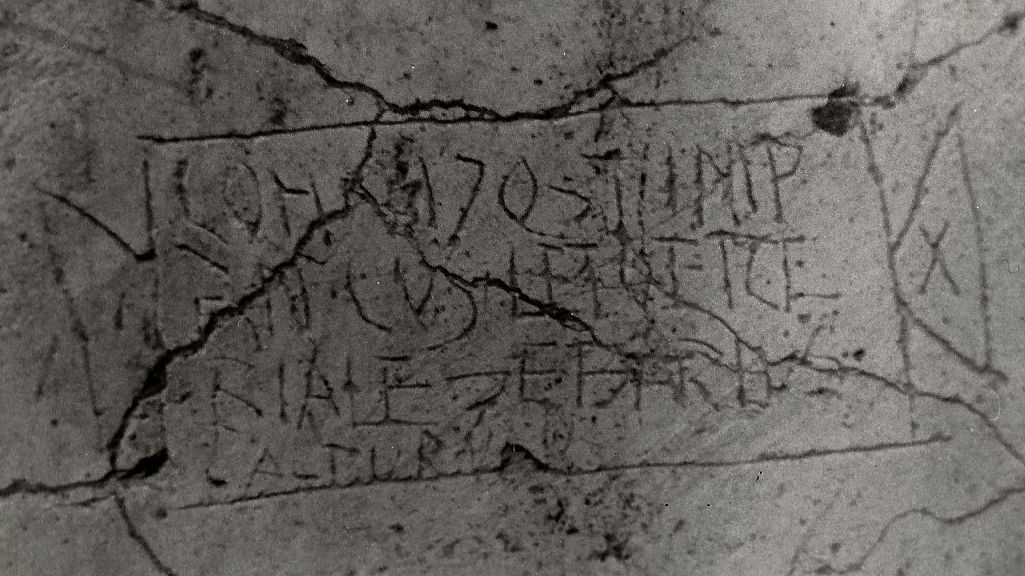

COH(orte) VI ((centuria)) OST(iensis) IMP(erante) AN(tonino) CO(n)S(ulibus) L(a)ETO ET CE RIALE SEBARIVS CALPVRNIVS, X |

From the sixth cohort, from the centuria of Ostiensis, during the reign of Caracalla, in the year of consuls Laetus and Cerialis, seba(cia)rius Calpurnius, vota decennalia |

| The graffito next to Silvanus in the Sacello del Silvano. Photo: Jan Theo Bakker. | |

The mosaic of the popa in front of the altar in the Sacello del Silvano. Photo: ICCD N015443.

The frumentum publicum-texts

The granting of the right to the frumentum publicum was celebrated by groups of vigiles through inscriptions on small marble slabs and painted texts. The slabs were later cut into pieces to hold hinges of doors or windows, and also ended up in a nearby lime kiln. Vaglieri assigns the reuse to the Severan period, in view of their dates (166, 168, 169, 175, 181, 182, 183, 190, and 202(?) AD). The reuse causes no surprise. In the Severan period the inscriptions will have been regarded as outdated. Unfortunately nothing can be said with certainty about their original place of attachment (see also below).

Painted texts were made for the same purpose. They are sometimes in a tabula ansata and have variously coloured backgrounds and letters. Not one of these preserves a consular date, but one can be dated to 161-166 AD on the basis of the career of an officer. The dates should not be taken as an indication that there had been a change regarding the right to the grain in the early third century, as suggested by Virlouvet.[4] An inscription from Moesia makes mention of it in 243 AD. The texts are reported on three locations:

In room 44, the first room to the south of the main vestibule in the east part of the building, are documented:

- in and on the south wall: a rectangular depression (0.40 x 0.67) and a shallow arched niche (0.40 x 0.19 x 0.08); a painted text next to the secondary door (still visible);

- in and on the east wall: two depressions (0.43 x 0.30; 0.33 x 0.54), one with remains of white and red plaster; a painted text in a partially preserved tabula ansata at 0.80 from the floor (still visible);

- on the north wall: a painted text in a tabula ansata, not deciphered (0.60 x 0.28);

- fragments of painted texts fallen from the walls;

- furthermore two recesses can be seen in the outer west wall, one a tabula ansata.

In room 43, the room to the south of 44:

- on the north wall: a painted text in a tabula ansata.

The second location is room 45, the room to the south of the Augusteum. Documented are:

- fragments of painted texts fallen from the walls;

- a variant of the tabula ansata, but the text had disappeared (still visible on the west wall; graffito nr. G0120).

Finally fragments of painted text were found to the north of the building, according to Vaglieri from the upper floors.

Remains of painted texts, recesses and a small niche in room 44. Photo: Jan Theo Bakker.

One of the empty recesses apparently contained a painted text, witness a few remains of painted plaster. It is not clear whether the others contained plaster or a marble slab.[5] The little niche in room 44, once surrounded by an aedicula-facade witness holes for the fastening, will have contained a bronze statuette, perhaps of the Genius Centuriae. In room 44 the recesses and texts are scattered over the walls in an irregular way. This suggests a rather informal character, even though high-ranking officers are mentioned.

The graffiti

Many graffiti can be seen on the bricks of the facade (that was never covered with plaster): on the pilasters flanking vestibules 1, 9 and 36, and to the left of the secondary entrance corridor 31. Many cannot be understood, but quite clear are the mention of cohorts (I, III, V, and VII), names, a date (May 18), and part of the Greek and Latin alphabet. Several vigiles clearly spelled out their name. For that reason, and in view of the size and position of the graffiti, we may conclude that the officers did not object to the scratching of the texts. They testify to loyalty and "esprit de corps", which may have been shown by men standing guard, by men returning at the end of a patrol, or by men upon leaving the guardhouse at the end of the four months.

Quite a few graffiti were written on the north wall of the vestibule ("pronaos") of the Augusteum. Two were made by a trumpeter (bucinator). A man from the first "Severan" cohort wrote for the well-being of Alexander Severus, whose name was erased after his damnatio memoriae. By a happy coincidence we know that another man, Apertius Nampamo, was later transferred to the Urban Cohorts and buried in his home town in Mauretania Caesariensis (Algeria). Room 45, the room to the south of the Augusteum, was a popular spot as well. Aelius Mansuetus identified himself as exactus lanternarum, overseer of the lamps and torches. Caius Licinius Felix celebrated the good outcome for himself and all of his comrades.

Quite remarkable and still unexplained is the large number of geometric drawings in room 45 and in room 44, the room to the south of the main vestibule with many painted texts and recesses in the walls: concentric circles, stacks of circles, rosettes, perhaps even a plan of one or more buildings.

In various other rooms graffiti can be seen, including drawings of ships and a tabula ansata. On the vault of a room below a staircase Marcus Valerius Severus used the word excubat, implying that the castra were regarded as an excubitorium, a guardhouse.

The vigiles after the middle of the third century

The last dated inscriptions are from the reign of Gordianus III, Emperor from 238 to 244 AD. From this we must not deduce that the vigiles left the barracks and Ostia soon afterwards. Many graffiti with a consular date were found in the excubitorium of the 7th cohort in Rome, the latest from 245 AD. The two series end during the tremendous crisis of the Empire in the middle of the third century. At an unknown point in time the Imperial administration must have taken the decision to withdraw the fire-brigade from Ostia. It could have been in the fourth century. Many coins from the building are from the reigns of Maxentius and Constantine, the latest are from the reign of Julianus (355-363 AD). The curved wall in front of basin 56 is of opus vittatum B that is surely later than the third century.

It is quite remarkable and exceptional that a complete series of statue bases was found in situ. Equally noteworthy is their state of preservation: they look like new. However, there are hardly any remains of sculpture: one portrait head and a fragment of a bronze statue. The statues must have been secured when the vigiles left the building. Much of the marble and travertine from the building was taken away in antiquity, but a ban may have been issued on the removal of the bases to lime kilns. The bases from the bench in the Augusteum were found lying on the ground, perhaps knocked down by the violence of an earthquake. Later they were covered by a thick layer of silt resulting from Tiber floods, until the building finally collapsed.

The neighbourhood

In the building to the west of the barracks, the Caseggiato delle Fornaci (II,VI,7), a bakery was installed in the period Antoninus Pius - Marcus Aurelius. It would make sense if a few of the millstones were operated for the vigiles (with one millstone producing flour, and therefore bread, for approximately 200 men). Two workshops to the north of the barracks may also have been active for the fire-brigade. In the Caseggiato della Fullonica (II,XI,2) and Fullonica II,XI,1 the special clothes of the men may have been cleaned and dyed.

It is conceivable that large cornerstones at ground level in the barracks and in the neighbourhood indicated that passages should not be blocked by wagons or animals, leaving a free passage for the fire fighters:

- four bases in the corners of the vestibule in the east side of the Caserma dei Vigili (II,V,1); av. h. 0.75;

- four bases in the corners of the vestibule in the south side of the Caserma dei Vigili (II,V,1); av. h. 0.90 (no stones in the blocked vestibule in the north side);

- four bases in the corridor between the Caseggiato delle Fornaci (II,VI,7) and the Casa del Soffitto Dipinto (II,VI,5); av. h. 0.90.

- four bases in the corners of a room at the south end of Via dei Vigili, in the Portico di Nettuno (II,IV,1); av. h. 1.00.

|

| Possible exit routes of the vigiles (orange) and large travertine bases at ground level (purple). |

Travertine bases in the vestibule in the east side of the Caserma dei Vigili. Seen from the west.

Two travertine bases in the north side of the vestibule in the south side of the Caserma dei Vigili. Seen from the north-west.

Two travertine bases in the south side of the vestibule in the south side of the Caserma dei Vigili. Seen from the south-west.

The blocked vestibule in the north side of the Caserma dei Vigili. No travertine bases. Seen from the south.

Two travertine bases in the east side of the (partially blocked) corridor in block II,VI. Seen from the south-east.

Two travertine bases in the west side of the (partially blocked) corridor in block II,VI. Sseen from the south-west.

Travertine bases at the south end of Via dei Vigili. Seen from the south.

Notes

[1] Virlouvet 1995, 272-282; Sablayrolles 1996, 331. Virlouvet and Sablayrolles more or less avoid this issue by suggesting that the real importance was the resulting eligibility for further donations (congiaria) and the rise in social status. In Rome, in 156 AD,Tiberius Claudius Messalinus, centurion of the fifth cohort, restored and enlarged a shrine of a Genius, using a special fund of his century: ex pecunia furfuraria centuriae suae (CIL VI, 222; EDR152610). Sablayrolles, following Henzen, argues that this "bran money" resulted from the sale by the vigiles of the bran obtained from the frumentum publicum: "The vigiles would thus have drawn additional income from the frumentum publicum by reselling the bran" (Sablayrolles 1996, 387 note 178). However, the vigiles will surely not have processed the free grain themselves, for bread eaten at home or in the guardhouse while on duty. It must have been processed in the mills of bakers, from which the bran resulted. After the milling the bakers would use the bran as animal fodder. Presumably the financial compensation was used by the vigiles to create a piggy bank.

[2] Another inscription might mention a vigiliarium, a watchtower, on the banks of the Tiber (CIL XIV, 254), but who used it and for what purpose is not made clear.

[3] Cébeillac-Gervasoni - Zevi 1976, 635. The available period is 212-217 AD. The authors suggest for Quintus Marcius Dioga the Prefecture of the Vigiles from 212-214 and the Prefecture of the Annona from 214-217.

[4] Virlouvet 1995, 273.

[5] To the best of my knowledge no attempts have been made to see if the slabs fit in some of the recesses in the walls.