The population: composition and social relations

Size of the population

It goes without saying that it is extremely difficult to establish, approximately, the size of the population of Ostia during its heyday, the second century. For the entire city, including the unexcavated area and the Ostian "Trastevere", Guido Calza (1941) reached an estimate of 36.000. Russell Meiggs (1960) suggested a total of between 50.000 and 60.000, an educated guess as he himself says. Other authors have suggested about half of Meiggs' estimate: 27.000 (James Packer in 1967) and 22.000 (Glenn Storey in 1997). In the same period Rome may have had a little under half a million inhabitants (Glenn Storey).

Origin of the inhabitants

Immigration can be deduced from explicit references in the inscriptions, from the so-called tribes of the Roman citizens, and from the names of the inhabitants. Meiggs and others have noted immigration from North Africa, Spain, Gaul, the Greek East, and various localities in Italy. Salomies adds more localities in Italy and Dalmatia, and notes that the remarkably high frequency of the praenomen (first name) Decimus, documented in 28 gentes (families), might be linked to immigration from Gallia Narbonensis, the south of France. Cébeillac-Gervasoni has stressed immigration from North Africa, concluding furthermore that these immigrants dominated life in Ostia. Salomies, noting that Africans can easily be recognized because of their distinctive nomenclature, also sees considerable immigration from North Africa, but believes that Cébeillac-Gervasoni is exaggerating somewhat. His general conclusion is that Ostia was a centre of immigration. Many members of the rising middle class of the second and third century did not have an Ostian origin.

Explicit references to the origin in the inscriptions are rare. Roman citizens were enrolled in a tribus, a tribe. The commonest tribe in Ostia was Palatina, followed by Voturia (abbreviated in inscriptions as PAL and VOT). Voturia was the old, original tribe of Ostia. Enrollment in Palatina started in the second century AD, but may then also be assigned to freedmen of old Ostian families. Other tribes imply an origin outside Ostia. Quirina for example was the most widely distributed tribe in North Africa.

The nomina of gentes, that is the names of the families or "clans" of Roman citizens in Ostia and Portus, were studied extensively by the Finnish scholar Olli Salomies (2002). He studied the names of 6.900 people from the harbours and 54.000 persons Rome. Some nomina are more common in Rome, some more frequent in Ostia. Cipius, Egrilius and Nasennius may be called characteristic for Ostia. Fifty-two nomina are found in Ostia and elsewhere, but not in Rome. Fifty-four nomina occur in Ostia, but nowhere else in the Empire. Here Salomies prefers to think of immigration, not of traditional Ostian names: imigration from outside Italy, because there can hardly have been any Italian cities from which people migrated only to Ostia, but not also to Rome. It is therefore not correct to call Ostia simply an extension of Rome. On the other hand, strong connections between Rome and Ostia can also be deduced from the nomina: thirteen nomina occur in Ostia and Rome, but nowhere else.

Salomies also looked at the chronological distribution, distinguishing between early texts, up to the second century AD, and later texts, from the second century AD and later. Twelve nomina do not appear any more after the early period. Fifty-one appear both in early and later inscriptions. In many of these gentes also the same praenomina (first names) were in use for centuries. Examples are Aulus Mucius and Aulus Egrilius. This suggests a continued presence. Many nomina are not attested before the middle of the second century. This can be taken as an indication of new arrivals.

It is to be expected that members of the governing class left clear onomastic traces, because numerous freedmen and descendants of freedmen took their name. A good example of this phenomenon in Ostia are the Auli Egrilii, more than 200 of which are documented. Salomies however also sees several magistrates whose nomen is not otherwise attested in Ostia, and several others who left only a few onomastic traces, in funerary epitaphs and in the lists of members of guilds. A striking and enigmatic example is that of the Publi Lucilii Gamalae, a very prominent family with only a handful belonging to the plebs, the "common people".

As to slaves and freed slaves: as a rule they retained their slave name as cognomen ("epithet") when freed, Felix for example. Quite common is the cognomen Mercurius (21 gentes), surely related to the commercial character of Ostia. When slaves working for the civitas Ostia or in the salt industry were freed, they received the nomen Ostiensis or Salinator. For some reason the Salinatores always have the praenomen Marcus, whereas six praenomina are documented for the Ostienses.

|

D(is) M(anibus) M(arcus) SALINATOR FORTV NATVS SALINATOR(ia)E IANVAR(i)A(e) FECIT ALV(m) N(a)E SVAE BENE MEREN TI |

|

Funerary inscription for Salinatoria Ianuaria, alumna (foster-daughter) of Marcus Salinator Fortunatus. The nomen Salinator indicates that Fortunatus had been a slave working in the salt pans. EDR080718. Photo: Marinucci 2012, 110 nr. 130. |

|

The names of slaves can be used as an indication for their origin, but it is a tricky criterion: slave owners could assign names of their choice. The names point especially to the Greek-speaking eastern half of the Empire. Slaves could be acquired in times of war. In peaceful times two important sources were the exposure of children, and the children of slaves. Slaves born in the household were called vernae.

An unknown number of inhabitants of Ostia did not fall into one of the above categories: the peregrini, freeborn men from the provinces without Roman citizenship. They use one name, followed by "son of", for example Eucharistus Demetri f(ilius). Only a few are found in the local guilds.

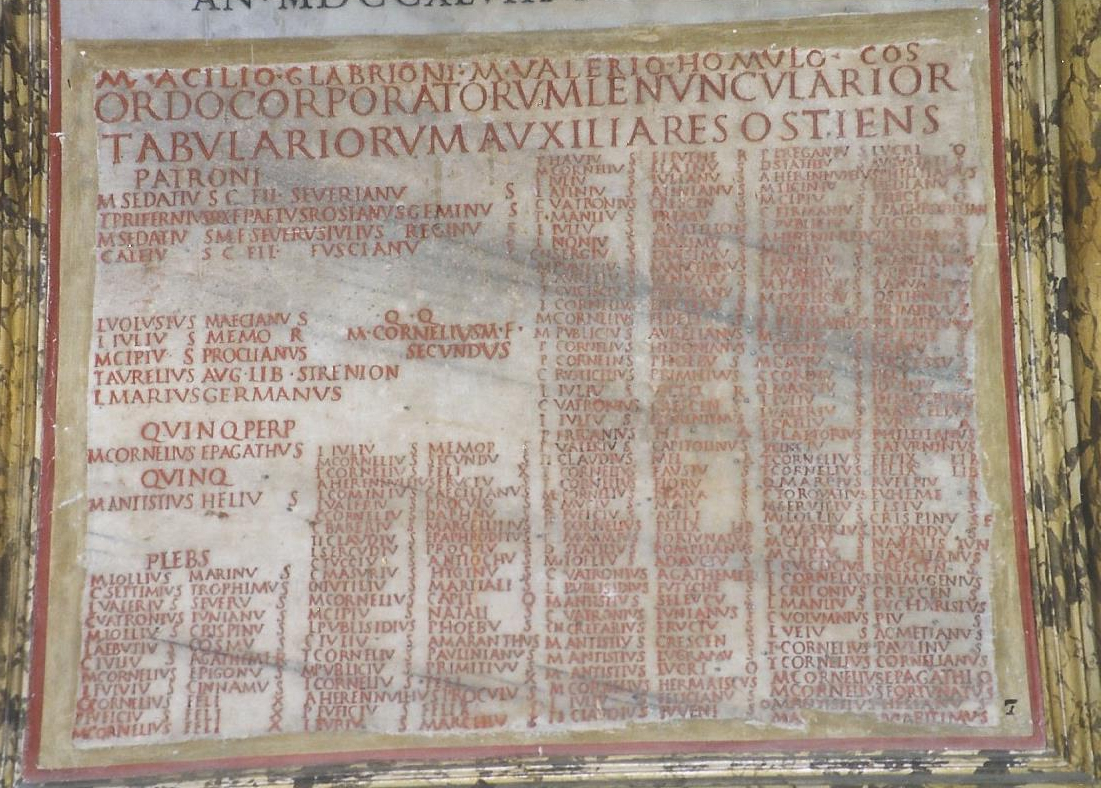

A list with the names of the members of a guild, from 152 AD.

EDR158649. Capitoline Museums. Photo: Eric Taylor.

Social relations

Social relations were discussed briefly by Russell Meiggs in his groundbreaking study Roman Ostia, published in 1960, updated in 1973. He stresses the role of freed slaves in the second and third century. The former masters became patrons of the freed slaves, and their relations were as a rule friendly. Inscriptions tell us that freedmen, freedwomen, and their descendants were often buried in the tombs of their patrons. The formula is: libertis libertabusque posterisque eorum. Funerary inscriptions also tell us that when relations got strained, freedmen could be barred from the tomb. On the other hand, freedmen regularly provided for the burial of the patron. Patrons regularly married former slaves, but marriages of freedmen with a daughter of the family were not common. In various ways freedmen were launched into business by their patron, providing money, which could lead to considerable wealth for the freedman. Freed slaves could also inherit property from the former master or mistress.

Freedmen had a well-defined place in society through a special priesthood in the Imperial cult. They could join the seviri Augustales, a group resembling a trade guild. In the organisation the so-called electi ranked highest. They seem to have been honorary presidents. The active presidents were four quinquennales. There were honorary quinquennales as well, and of course ordinary members. Freedmen were also in charge of the Imperial cult at shrines of the wards (vici) of Ostia, part of the ancient regiones. At the compita, shrines at crossroads, they worshipped the Genius and Lares of the Emperor, his guardian spirit and household deities, as magistri vici.

Slaves were owned by private people, with the Emperor as a very important owner, and the city. It was common for freedmen to buy slaves themselves. Slaves born in the household (vernae, whether a child of the patron or of two slaves) were often treated by the patrons as if they were their own, free children - at least, that is what phrases in funerary inscriptions suggest. In a rich household these slaves probably lived in better circumstances than free citizens living in a crowded apartment building. But slaves could also be sold and used for hard manual labour, under conditions we know little about.

Meiggs notes that women too could own slaves and property, including workshops. They are mentioned in affectionate terms in funerary inscriptions. They appear next to their husbands in reliefs of the dextrarum iunctio, the joining of the right hands, and feature in painted mythological scenes in tombs. One woman left money in her will for the upbringing of one hundred girls, thus following an example set by Antoninus Pius, who honoured his deceased wife Faustina by the institution of puellae alimentariae Faustinianae. Women are not encountered in the trade guilds, but featured prominently in religious life, also having their own cult, that of Bona Dea.

Painting of a dextrarum iunctio in tomb 19 of the Isola Sacra Necropolis. Photo: Gerard Huissen.

The age of marriage is rarely recorded. Girls could marry before the age of 15. Looking at the number of children buried with their parents, a common practice, family size seems to have been small: one or two children was probably the general rule. A family with more than five children is not documented, and only four families are known to have had more than three children. Adoption occurred very frequently. The civil code contains many laws about the tutela, the guardianship. Adopted children were called alumni and alumnae.

The age of death is recorded in approximately 600 funerary inscriptions. It is important to realize that the age of very young children and of people who lived to be quite old is more likely to be recorded. The numbers for the first 10 years suggest that the death rate of boys was higher than that of girls. Between the ages of 20 and 30 the death rate of females is higher, a result of complications when giving birth, one would think.

|

DIS MANIBVS Q(uinti) VOLUSI SP(uri) F(ilii) LEM(onia) ANTHI PARVOLVS IN GREMIO COMVNIS FORTE PARENTIS DUM LVDIT FATI CONRVIT INVIDIA NAM TRVCIBVS IVNCTIS BVBVS TVNC FORTE NOVELI IGNARVM RECTOR PROPVLIT ORBE ROTA MAESTVS VTERQVE PARENS POSTQVAM MISERABILE FVNVS FECIT INFERIS MVNERA SVMA DEDIT HVNC ANTHO TVMVLVM MALE DEFLORENTIBVS ANNIS PRO PIETATE PARI COMPOSVERE SVO Q(uintus) VOLVSIVS Q(uinti) L(ibertus) ANTHVS PATER FECIT SIBI ET SILIAE ((mulieris)) L(ibertae) FELICVLAE CONIVGI SANCTISSVMAE VOLVSIAE Q(uinti) F(iliae) NICE Q(uinto) VOLVSIO Q(uinti) F(ilio) ANTHO SILIAE ((mulieris)) L(ibertae) NICE C(aio) SILIO ANTHO IN FR(onte) P(edes) VI IN AGR(o) P(edes) III ((semis)) |

To the departed spirits. Of Quintus Volusius Anthus, son of Spurius, of the tribe Lemonia. A little boy, in the protection of a common parent, while he played, fell down by chance by way of the envy of fate. For at that moment, a carter with yoked wild oxen ran over by accident the unknowing child with the rim of a wheel. After the two mourning parents performed the miserable funeral and gave the final gifts as grave-offering, now, to Anthus, as his years fade away wretchedly, they have set up this tomb with equally matched affection to their own. Quintus Volusius Anthus, freedman of Quintus, father, made this for himself and for Silia Felicula, freedwoman of a woman, his chaste wife, for Volusia Nice, daughter of Quintus, for Quintus Volusius Anthus, son of Quintus, for Silia Nice, freedwoman of a woman, for Gaius Silius Anthus. Six feet in frontage, three-and-a-half in depth. |

|

A funerary inscription on a marble slab, found in Ostia in 1789. Vatican Museums, Galleria Lapidaria. EDR143627. Translation: Peter Keegan. The boy Anthus was run over by a cart. "Son of Spurius" means that Anthus was an illegitimate child, not born in a legally recognised marriage. This means that a slave was involved. The father, also called Anthus, was a freed slave of Quintus Volusius, but he had the child when still a slave: illegitimate children took their name from their mother, in this case Volusius from Volusia. This means that the mother was a freedwoman of Quintus Volusius. Later the father married Silia Felicula. At the end of the inscription another Anthus is mentioned, son of Felicula and half-brother of the deceased boy. |

|

About crime there is little or no evidence from the harbours, but of course things could go wrong and the law will have been broken regularly: mismanagement by guardians of orphans, forced prostitution of slaves (when it was not stipulated in the sales contract), theft, fraud, physical violence, murder, and in the harbours in particular theft by inn-keepers and sailors, and from warehouses. People could be put in prison before a hearing or awaiting trial, but emprisonment was not a known form of punishment. Instead, fines were applied, physical punishment and forced labour. Access to the city could be denied.

The "social revolution"

Meiggs distinguishes a few main phases in the development of the governing class. Until the end of the first century AD it was composed of a narrow aristrocracy, he says. Starting in the Flavian period we see the rise of a wealthy middle class, including freedmen, with business interests. This tendency kept developing until the middle of the third century AD. Many of the early families seem to have left Ostia, died out, or lost their place in the governing class. With the economic crisis of the third century the middle class collapsed, and the gulf between rich and poor widened. At the end of the third century rich domus begin to appear, houses that were decorated lavishly with (reused) marble on the floors and walls, fountains and statues.

A row of domus from the 3rd and 4th century, on Via della Caupona. Photo: Bing Maps.

The Ostia of the second and third century was characterized not only by new arrivals, but also by the extensive manumission of slaves. "The freedman is at the very centre of Ostian society", concludes Meiggs. He uses the phrase "social revolution" for the rise of a commercial middle class in the second century, largely made up of new arrivals and freed slaves. This notion has been modified by Henrik Mouritsen. He argues that the general picture is distorted by the funerary inscriptions. Freeborn grave owners are hardly found in these documents, but freeborn citizens are represented very well as members of guilds and as local, high-ranking officials. Mouritsen concludes that freed slaves were intent on identifying themselves as such in their tombs, celebrating their new social status, unlike the freeborn citizens, who did not feel that need, perhaps even finding it vulgar and in bad taste. The children of freed slaves, who were freeborn citizens too, are also underrepresented in the funerary inscriptions and apparently did not feel the need anymore.

Daily life

Daily life in Ostia is in need of many more studies, even though two books were dedicated to it: Carlo Pavolini's La vita quotidiana a Ostia from 1986 (unfortunately not translated into English) and Gregory Aldrete's Daily life in the Roman city. Rome, Pompeii and Ostia, from 2004. Many topics are discussed in the freely accessible collection of articles Life and death in a multicultural harbour city: Ostia Antica from the Republic through Late Antiquity, published in 2020: marriage, children, clothes, jewellery, games, and so on.