Those who walk from the Colosseum to the Circus Maximus will see to the right, after passing the Arch of Constantine and the Palatine ticket office, a row of cypresses behind a fence. This is the location of the Septizodium, a huge construction, the remains of which were torn down by pope Sixtus V (1585-1590). A modern pavement represents the plan, with three large apses. The Historia Augusta states that, "when Severus built the Septizonium he had no other thought than that his building should strike the eyes of those who came to Rome from Africa". However, the monument was at the end of the Via Appia, which was not used by visitors from Africa. They sailed to Ostia and Portus, and used the Via Ostiensis and Via Portuensis.

The outline of the Septizodium, to the right of a row of cypresses. On the spot of the three apses are round trees. Bottom left the Circus Maximus.

Photo: maps.bing.com.

The Septizodium (also called Septizonium) is mentioned in a few ancient texts:

| Opera publica praecipua eius exstant Septizonium et Thermae Severianae. | The principal public works of his now in existence are the Septizonium and the Baths of Severus. |

| Historia Augusta, Septimius Severus 19,5. Translation: David Magie. | |

| Cum Septizonium faceret, nihil aliud cogitavit, quam ut ex Africa venientibus suum opus occurreret. Nisi absente eo per praefectum urbis medium simulacrum eius esset locatum, aditum Palatinis aedibus, id est regium atrium, ab ea parte facere voluisse perhibetur. Quod etiam post Alexander cum vellet facere, ab haruspicibus dicitur esse prohibitus, cum hoc sciscitans non litasset. | When he built the Septizonium he had no other thought than that his building should strike the eyes of those who came to Rome from Africa. It is said that he wished to make an entrance on this side of the Palatine mansion - the royal dwelling, that is - and he would have done so had not the prefect of the city planted his statue in the centre of it while he was away. Afterwards Alexander wished to carry out this plan, but he, it is said, was prevented by the soothsayers, for on making inquiry he obtained unfavourable omens. |

| Historia Augusta, Septimius Severus 24,3-5. Translation: David Magie. | |

| Funus Getae accuratius fuisse dicitur quam eius qui fratri videretur occisus. Inlatusque est maiorum sepulchro, hoc est Severi, quod est in Appia Via euntibus ad portam dextra, specie Septizonii exstructum, quod sibi ille vivus ornaverat. | The funeral of Geta was too splendid, it is said, for a man supposed to have been killed by his brother. He was laid in the tomb of his ancestors, of Severus, that is, on the Via Appia at the right as you go to the gate; it was constructed after the manner of the Septizonium, which Severus during his life had embellished for himself. |

| Historia Augusta, Geta 7,1-2. Translation: David Magie. | |

| Hoc imperante Septizonium et thermae Severianae dedicatae sunt. | While he was ruling the Septizonium and the Severan baths were dedicated. |

| Chronograph of 354 (Calendar of Filocalus), Imperia Caesarum. | |

| Diebusque paucis secutis cum itidem plebs excita calore quo consuevit vini causando inopiam, ad Septemzodium convenisset, celebrem locum, ubi operis ambitiosi nymphaeum Marcus condidit imperator. | And a few days later the people again, excited with their usual passion, and alleging a scarcity of wine, assembled at the Septemzodium, a much frequented spot, where the emperor Marcus Aurelius erected a nymphaeum of pretentious style. |

| Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae (Roman History) 15.7.3 (355 AD). Translation John C. Rolfe. | |

| Severo imperante, thermae Severianae apud Antiochiam, et Romae factae, et Septizonium exstructum. | During the reign of Severus, Severus baths were made at Antiochia, and Rome, and the Septizonium was constructed. |

| Hieronymus, Chronicle 2216. | |

| Fabianus et Mucianus. His consulibus thermae Severianae apud Antiochiam et Romae factae, et Septezodium instructum est. | Fabianus and Mucianus. Under these consuls Severan Baths were built at Antioch and Rome, and the Septezodium erected. |

| Cassiodorus, Chronica, Imperatores romani | |

| Septizonium divi Severi. | The Septizonium of the deified Severus. |

| Curiosum and Notitia, Regio X, Palatium. | |

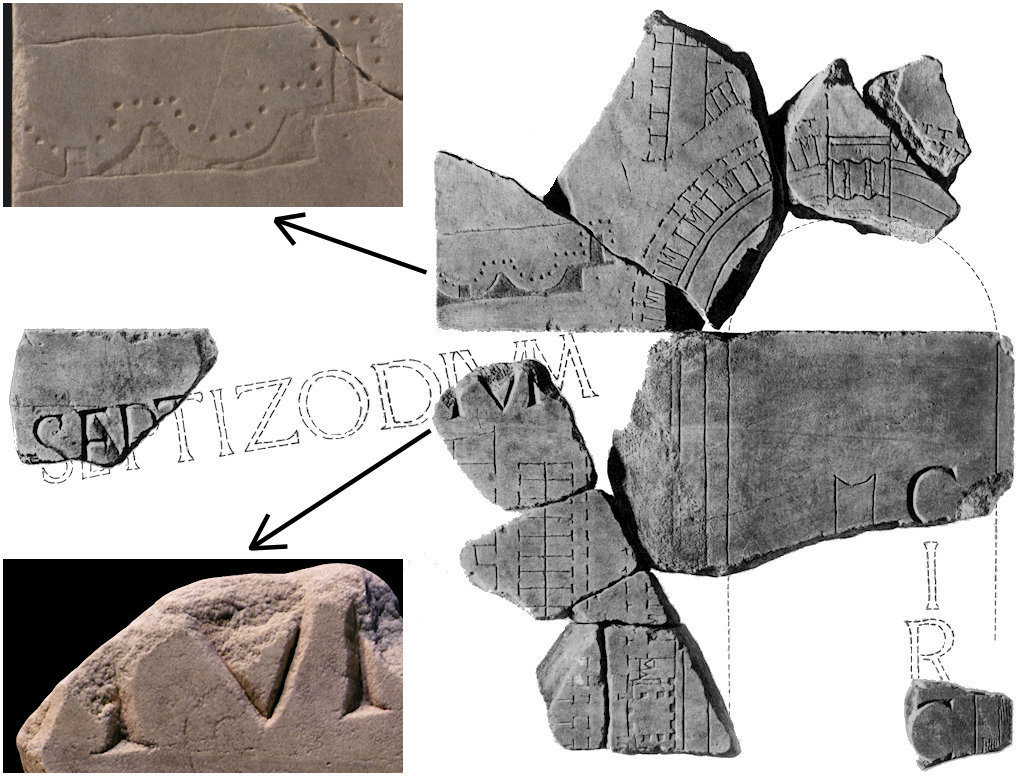

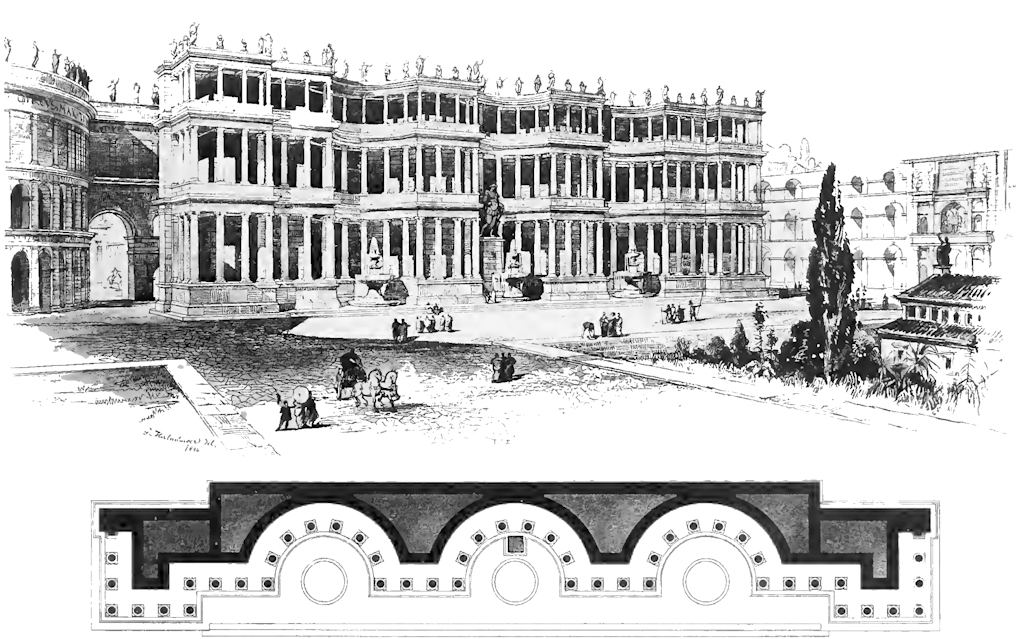

The first scholarly study of the structure was published in 1886 by Christian Huelsen. There has never been doubt about the location and the identification of the remains of the Septizodium, because of the information provided by the ancient texts and toponyms, such as the church S. Lucia in Septisolio. Already in the 19th century archaeologists started studying the re-use of the various kinds of stone from the Septizodium. It was used on many spots, among others as base for the obelisk on Piazza del Popolo. The building has been reconstructed on the basis of many old descriptions and drawings, and of a fragment of the Severan marble plan of Rome, the Forma Urbis Romae. It must have been approximately 95 meters wide and 30 high. In essence it was a three-storied facade of columns. It must have been decorated with statues, apparently with a statue of the Emperor in the centre.

|

The Septizodium and the Circus Maximus on fragments of the Forma Urbis Romae. A small part of the curve of the letter D has been preserved.

Images: Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project.

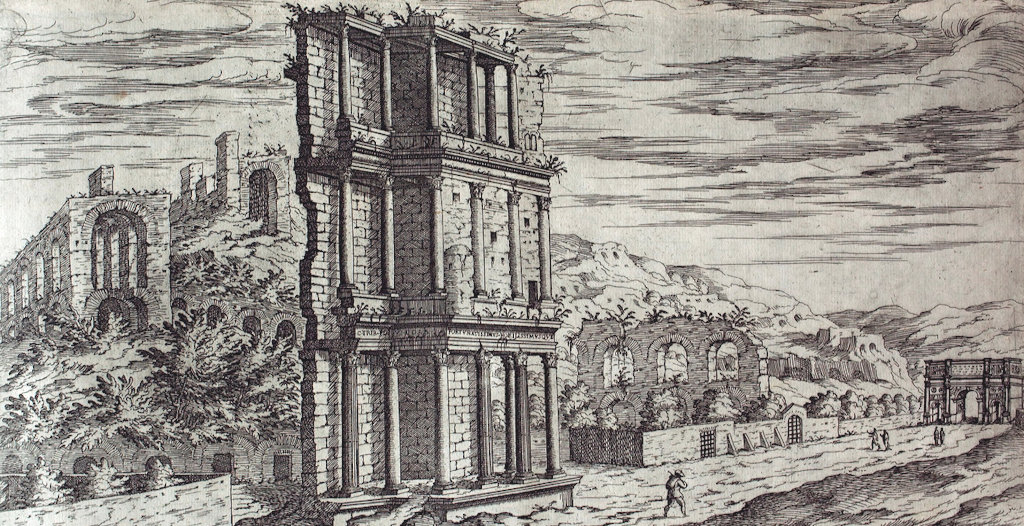

The Septizodium in the late 16th century.

Etienne Du Pérac, I vestigi dell'antichità di Roma raccolti et ritratti in perspettiva, Roma 1575, Tav. 13.

|

Click on the image to enlarge. Reconstruction drawing and plan of the Septizodium by P. Graef.

Image: Huelsen 1886, Taf. 4.

The dedicatory inscription is lost, but in the past a large part of it was written down. It was a single line on the architrave of the ground floor and included the titulature of Septimius Severus and Caracalla. The date has been debated, because past authors give various readings for the tribunicia potestas of Caracalla (V and VI), which leaves the period 10 December 201 - 9 December 203 AD. Cassiodorus gives a consular date of 201 AD.

| IMP(erator) CAES(ar) DIVI M(arci) ANTONINI PII GERM(anici) SARM(atici) FIL(ius) DIVI COMMODI FRATER DIVI ANTONINI PII NEP(os) DIVI HADRIANI PRONEP(os) DIVI TRAIANI PARTH(ici) ABNEP(os) DIVI NERVAE [---] AVG(ustus) TRIB(unicia) POT(estate) V[I?] CO(n)S(ul) FORTVNATISSIMVS NOBILISSIMVSQVE [---] |

| Dedicatory inscription of the Septizodium. EDR104092. |

The word Septizonium is encountered already in Suetonius, who says that Titus was born "near the Septizonium, in a mean house, and a very small and dark room, which still exists, and is shown to the curious" (prope Septizonium sordidis aedibus, cubiculo vero perparvo et obscuro, nam manet adhuc et ostenditur; Suetonius, Titus 1). Was this a predecessor of Severus' Septizodium? However, the reliability of the manuscripts has here been questioned. In the middle of the third century, the Christian poet Commodianus speaks of "septizonium" in the context of astronomy (Commodianus, Instructiones, De septizonio et stellis ("Of the Septizonium and the Stars")).

Septizodia are mentioned in a few inscriptions from North Africa, Sicily, and Britain. The variants septizonium, septisonium, septizodium, and septidonium are documented (the late-antique Appendix Probi, listing spelling errors, says: septizonium non septidonium):

- Cincari (Henchir Tounga, Tunisia). A septidonium that is perhaps linked to a row of seven niches; EDCS-70300069; 200-250 AD.

- Avedda (Henchir Bedd, Tunisia). A citizen is honoured by the city for erecting a septizodium; EDCS-25300094; 197-300 AD.

- Lambaesis (Tazoult, Algeria). According to the inscription a septizonium decorated with marble and mosaics; EDCS-20600107; 246-248 AD.

- Lilybaeum (Marsala, Sicily). Mentions a ward (vicus) named after a septizodium; EDCS-12800324; 200-300 AD.

- Ratae Corieltauvorum (Leicester, England). A curse tablet: thieves should die within seven days in a septisonium; EDCS-46400877; 150-250 AD.

|

||

|

qu[i a]rgentios Sabiniani fura verunt id est Similis Cupitus et Lochita hos deus siderabit in hoc septiso nio et peto ut vitam suam per dant ante dies septem |

those who have stolen the silver coins of Sabinianus, that is Similis, Cupitus, and Lochita, a god will strike down in this septisonium and I ask that they lose their life before seven days |

Curse tablet from Leicester. Drawing: Tomlin 2008, p. 213. |

The Septizodium in Rome has been compared to elaborate facades of fountains and theatres, and it is often said that it was a nymphaeum. This is also stated by Ammianus Marcellinus and has been confirmed by excavations. But it is hard to believe that it served merely as a facade, to impress visitors, as the Historia Augusta would have it. And why was it called Septizodium or Septizonium? Septizodium leads us to the zodiac, septizonium to seven zones or spheres. The first explanation is problematic, because there are twelve astrological signs. The second might coincide with the seven classical planets (Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) or the deities of the seven days of the week. The requested death of the thieves from Leicester within seven days is hardly a coincidence (the usual deadline for requested deaths on British curse tablets is nine days). And is there also a link between "septi" and Septimius?

A link with the planets and the Zodiac finds support in evidence provided by the ancient historians: "Being worried about the future, he had recourse to an astrologer in a certain city of Africa ... he made inquiries about the horoscopes of marriageable women, being himself no mean astrologer ... he was indicted for consulting about the imperial dignity with seers and astrologers ... learning it from astrology, in which he was very skilled" (Historia Augusta, Severus 2,8, 3,9, 4,3, 9,6); "He knew this chiefly from the stars under which he had been born, for he had caused them to be painted on the ceilings of the rooms in the palace where he was wont to hold court, so that they were visible to all ... he knew his fate also by what he had heard from the seers" (Cassius Dio 77,11).

|

Busts of the seven days of the week and the Emperor: Diana Mars Mercurius Jupiter Venus Septimius Severus Saturnus Apollo |

|

IOVI OPTIMO MAXIMO ET C{A}ETERIS DIS DEABVSQ(ue) IMMORTALIBVS PRO SALVTE IMPERATOR(um) L(uci) SEPTIMI SEVERI ET M(arci) AVRELI ANTONI[ni] |

Octagonal base or altar in the Château de Golas (near Vienne, France). EDCS-09200591. 198-209 AD. Photo: Ledauphine.com.

E. Espérandieu, Recueil général des bas-reliefs de la Gaule romaine, Paris 1907, volume I, 281-282 nr. 412.

A coin from Hadrianopolis in Thracia, from the reign of Septimius Severus, shows a structure that is very similar to the Septizodium. We see three stories with columns and statues. In the centre of the ground floor is a reclining figure, presumably the personification of a river. At the sides seem to be the Dioscures, Castor and Pollux, with horses. Noteworthy is a structure at the front with seven circles, perhaps a basin with water spouts.

Coin from Hadrianopolis in Thracia. Reign of Septimius Severus. Photo: Lusnia 2004, fig. 14.

Literature

- P. Aupert, Le nymphée de Tipasa et les nymphées et 'septizonia' nord-africains, Rome 1974.

- A. Bartoli, "I documenti per la storia del Settizonio severiano e i disegni inediti di Marten van Heemskerck", Bollettino d'arte 3 (1909), 253-269.

- P. Chini - D. Mancioli, "Il settizodio: Saggi di scavo - Considerazioni preliminari", Bullettino della Commissione archeologica Comunale di Roma 91 (1986), 499-502.

- T. Dombart, Das Palatinische Septizonium zu Rom, München 1922 (review: E. Brandenburg, Archiv für Orientforschung 3 (1926), 20-22).

- N. Duval - N. Lamare, "Une petite ville romaine de Tunisie: le Municipium Cincaritanum", Mélanges de l'école française de Rome, Antiquité 124,1 (2012), 231-288.

- C. Gorrie, "The Septizodium of Septimius Severus Revisited: the Monument in Its Historical and Urban Context", Latomus 60,3 (2001), 653-670.

- J. Guey, "Note sur le Septizonium du Palatin", Mélanges société toulousaine d'études classiques 1 (1946), 147-166.

- K. Hampe, "Ein ungedruckter Bericht über das Konklave von 1241 im römischen Septizonium", Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse 4,1 (!913), 3-34.

- Ch. Huelsen, Das Septizonium des Septimius Severus, Berlin 1886.

- I. Iacopi I. - G. Tedone, "La ricostruzione del Settizodio severiana", Bolletino di archeologia 19-21 (1993), 1-12.

- I. Iacopi - M. Tomei, "Il Settizodio severiana", Bolletino di archeologia 1-2 (1990), 149-155.

- S.S. Lusnia, "Urban Planning and Sculptural Display in Severan Rome: Reconstructing the Septizodium and Its Role in Dynastic Politics", American Journal of Archaeology 108,4 (2004), 517-544.

- S.S. Lusnia, "Redating the Septizodium and Severan Propaganda", Common Ground: Archaeology, Art, Science, and Humanities, Oxford 2006, 196-199.

- C. Pappelau, "The Dismantling of the Septizonium - a Rational, Utilitarian and Economic Process?", Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 2. Zentren und Konjunkturen der Spoliierung, Berlin 2017, 357-379.

- C. Pappelau, Das Septizonium des Septimius Severus.Geschichte, Niederlegung, Transport und Wiederverwendung seiner Baumaterialien, Berlin 2020.

- E. Petersen, "Septizonium", Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 25 (1910), 56-73.

- G. Picard, "Le septizonium de Cincari et le probleme des septizonia", Monuments et mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot 52,2 (1961), 77-93.

- E. Stevenson, "Il Settizonio severiano e la distruzione dei suoi avanzi sotto Sisto V", Bullettino della Commissione archeologica Comunale di Roma 1888, 269-298.

- E. Thomas, "Metaphor and Identity in Severan architecture: The Septizodium at Rome between reality and fantasy", Severan culture, Cambridge 2007, 327-367.

- R. Tomlin, "Paedagogium and Septizonium: Two Roman Lead Tablets from Leicester", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 167 (2008), 207-218.

- E.R. Varner, Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture, Leiden 2004.