The mills-bakeries of Ostia

Jan Theo Bakker

Introduction

Roman bakeries were usually mills-bakeries. Only in later antiquity can we make a distinction between the milling and baking, namely after the introduction of water mills, such as have been found on a steep slope of the Ianiculum in Rome and near Arles (the Barbegal). Until the mid-1980's two of these mills-bakeries had been identified in Ostia: the House of the Millstones (I,III,1), to the east of the well-known House of Diana, and Mill I,XIII,4, in the south part of town. A Dutch team studying the bakeries was then able to identify five or six more. One of these establishments, near the museum, has disappeared completely, and is known only from the excavation diaries. The identification of Building II,VIII,9, to the east of the Great Warehouse (II,IX,7), remains uncertain. Only the south part of the building has been unearthed, and further excavation may show whether it was indeed a bakery. No doubts remain about the function of the House of the Ovens (II,VI,7), House I,IX,2, the House of the Wooden Balcony (I,II,2.6), and finally the House of the Cistern (I,XII,4). The final publication of the Dutch team included a full description and analysis of three Ostian bakeries: The House of the Millstones, the House of the Ovens, and Mill I,XIII,4. The remaining workshops were studied in a concise manner.

During its heyday Ostia may have had some 20.000-25.000 inhabitants. In the third century, a period of deep crises, this number must have decreased considerably, and so must the number of bakeries. In late antiquity the city became a pleasant seaside living environment. Several commercial buildings were modified drastically and changed into wealthy habitations. In the early fifth century the final decline set in. Buildings were looted, marble was taken to lime kilns, and metal objects were melted down. Obviously then, the number of bakeries that can be recognised today must be smaller than the total during Ostia's golden age. When the population shrunk, the number of bakeries was reduced accordingly. The discarded bakeries could be reused for other purposes, or left as they were. It should furthermore be remembered that only some two-thirds of the city have been excavated.

Map of the distribution of the bakeries.

The appearance of the mills-bakeries

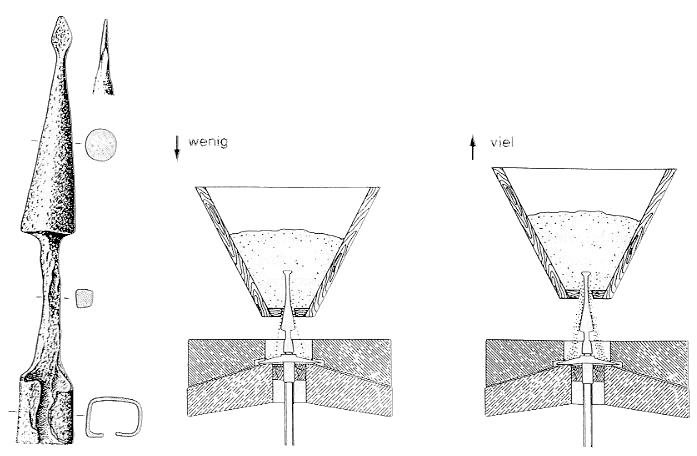

The bakeries have a lot in common, and the technical achievement was quite considerable. The workshops are quite large, and cover a ground floor area ranging from 640 to 1525 square meters. On average the bakeries contained nine millstones. A millstone consisted of two parts: an immobile, conical base (meta) and on top of that a stone that was shaped like an hour-glass (catillus). Mules or horses were attached to a wooden frame over the catillus. They walked in circles and rotated the catillus over the meta. The grinding took place between the two parts, that were at a very small, fixed distance. If the distance was too small, the grain would have been burnt, and if it was too large, too much bran would have remained. Specialist carpenters maintained the machines. Many of their tools were actually found in the House of the Millstones, where they also had a small workshop, the shop-sign of which can still be seen in the east facade. In the interior of the millstones, dosage cones were used.

Relief of a millstone, from tomb 78 of the Isola Sacra necropolis. Photo: Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica.

|

|

Reconstruction drawings of a millstone. From Pascolini 1978 and Adam 1984, fig. 735.

Drawing of a dosage cone (left) and of the use (right).

From Baatz 1994, fig. 20,12 and fig. 14.

Machines were also used for the kneading. Like the millstones they were made of porous volcanic stone. They are bowls in which the dough was kneaded by a combination of fixed and rotating blades. A few blades were inserted in the side of the bowl, and a few were attached to a vertical bar. People pushed a horizontal bar that set the mixing device in motion.

Cross-section of a kneading-machine.

From Blümner 1912, fig. 26, p. 65.

Huge, well-ventilated halls were built for the machinery. Often the first floor formed part of the workshop as well. Grain was led from there to the millstones through wooden pipes. The floors suffered a lot, and were therefore covered with basalt blocks, in which imprints of hooves remain. Many basins are found, because water was needed in very large quantities, for the kneading, as drinking water for the animals, for moistening the grain before milling and so on. The bread was baked in huge ovens, consisting of a base with a cupola that had an inside diameter of 3.5 to 5 meters. Wood was burned inside the cupola, sometimes below rotating grates on which the bread was placed.

A marble block in which urns were inserted, found in Ostia, now in the Vatican. It was made by P. Nonius Zethus, Aug(ustalis), for himself,

the freedwoman Nonia Hilara and his wife Nonia Pelagia. To the left and right of the inscription the interior of a bakery is depicted.

First century AD. CIL XIV, 393. Photo: Mary-Jane Cuyler.

To the left of the inscription an ass or donkey is turning a millstone. Over the millstone is a wooden contraption to which the animal was attached.

In the center is a hopper through which grain was led into the millstone. To the left side a hammer and a bell are attached. The bell started ringing

when the hopper was empty. The flour fell in a wooden basket or masonry bowl around the lower part. In the upper right part is a whip.

Photo: Mary-Jane Cuyler.

To the right are several objects that were used in a bakery: at the top perhaps a bread-mould, a grain measure, and a sieve,

at the bottom two baskets, two grain measures, and perhaps two leveling sticks to be used with the grain measures.

Photo: Mary-Jane Cuyler.

The Ostian bakeries may be called factories, especially when they are compared to their counterparts in Pompeii. The latter contained only three to four millstones, very close to each other. The spacious Ostian bakeries must have been operated in a much more efficient way and more hours per day. However, waterpower was not used for the milling in Ostia. Many water wheels have been found in the city, but they all supplied baths. Rough and admittedly tentative estimates can be made of the production capacity of the millstones. A millstone in Pompeii must have supplied some 90 people, if it is true that the city had approximately 10.000 inhabitants. A water-powered millstone could serve between 320 and 690 people. An Ostian millstone may have produced flour for some 150 to 300 people. This means that, in the second century and with a population of 20.000-25.000, there must have been approximately 100 millstones in 10 or more bakeries. A few bakeries are therefore still to be excavated or identified.

The dates and distribution of the bakeries

More than half of the buildings in Ostia were erected during the reign of Hadrian, shortly after the completion of Trajan's harbour. In this period many bakeries must have been built, but of the identified bakeries only one (Mill I,XIII,4) can be assigned to it. The other workshops were installed at various points in time from the reign of Antoninus Pius to the Severan period, that is, during the next 100 years. Often Hadrianic buildings were altered for the purpose. This is a most surprising development. For example, the House of the Ovens is situated to the west of the Barracks of the Fire Brigade and most likely served the fire fighters. The Barracks were built under Hadrian, but the bakery was installed later, during the reign of his successor, in Hadrianic shops. Apparently the bread for the fire fighters was originally prepared elsewhere in town.

Equally surprising is the distribution of the bakeries. There is a concentration in the centre of town, especially to the east of the Forum. Exceptions are the House of the Ovens, the position of which was probably dictated by the Barracks, and Mill I,XIII,4, the only bakery from the early second century. Why were so many bakeries - noisy workshops, where slaves and convicted criminals toiled in flour dust - located and tolerated near the representative and monumental centre of town? Two bakeries even flank the Decumanus Maximus, a clear disfigurement of Ostia's main street. It causes little surprise that this situation was corrected much later, when these two bakeries had been abandoned: a large, decorative apse and a nymphaeum were then installed in rooms along the Decumanus.

Map of the city centre with the distribution of the bakeries.

Horrea for grain: light blue - Dolia defossa: dark blue - Other store buildings: yellow.

Bakeries: purple - Isolated finds of millstones and kneading-machines: green circles.

The Great Warehouse

A least a partial explanation for the distribution is found quickly. The bakeries in the centre of town are near the Great Warehouse, one of Ostia's largest warehouses for grain. After the reign of Hadrian one bakery after the other was installed near the Great Warehouse: the House of the Wooden Balcony, the House of the Cistern, a bakery near the museum, the House of the Millstones, and perhaps a bakery to the east of the warehouse. The House of the Millstones had a direct connection with the warehouse, through a roof over the street. We seem to witness rationalisation, economic simplification of the bakers' trade. Apparently it was more practical or cheaper if the bakeries were situated near their main raw material.

The warehouse dates back to the reign of Claudius and Nero. It was rebuilt and extended during the reign of Commodus and the Severan Emperors. Eventually it could hold between 5.660 and 6.960 tons of grain, enough to feed at least 14.000 people for one year. The size, quality and complexity of the Great Warehouse suggested to Rickman that it was Imperial property. In the first century Ostia had few high-rising buildings, and must in this respect have been similar to Pompeii. The colossal building must have made quite an impression.

The Shrine of Silvanus

For the study of the bakers' trade in Ostia we possess various other sources that are quite informative: reliefs, inscriptions, legal texts, and in particular a shrine with wall paintings and graffiti. This shrine is a narrow and dark room in the back part of the House of the Millstones. It could only be entered by passing through the entire bakery. It was excavated partly in 1870, when fifty bronze and silver statuettes were found. Unfortunately many of these were stolen during the excavation, and we do not know which deities they represented. The bakery and the shrine were excavated completely from 1913 to 1916. It became clear that the bakery had been destroyed by fire and had not been rebuilt. Coins and the masonry suggest that the fire occurred at the end of the third century. As a result, many objects were unearthed. Some were related to the workshop, such as parts of horse harnesses, bells that rang when the hopper was empty, and metal parts of dosage cones for the millstones. Other finds were related to surprisingly wealthy habitations on the upper floors: bronze revetment of furniture, sometimes with silver inlay, marble and terracotta friezes, fragments of black-and-white mosaic floors and of painted ceilings, tiny columns, marble revetment, and so on.

After the 1870-excavations only a few objects were found in the shrine, but on the walls many paintings were found of people and deities. The main deity in the shrine was Silvanus, a god of the woods. The room was therefore called Shrine of Silvanus by the excavators. Silvanus was depicted next to the entrance, on the outer wall. He was also painted in the back part of the room. The latter painting, which is now in the storage rooms of Ostia, once had a painted text, stating that it had been made after a vision: Silvanus had appeared to one of the bakers in a dream. Next to Silvanus one can still read the following graffito: "Calpurnius, night-watchman from the centuria of Ostiensis, from the sixth cohors, during the reign of Caracalla, in the year of consuls Laetus and Cerialis [215 AD], X". Calpurnius, a fire fighter from Rome, stationed in Ostia, patrolled through the city at night with a torch. "X" means that he prayed for "ten more years for Caracalla", as the Americans would say today. On the opposite wall Calpurnius scratched the exact day on which he visited the shrine: April 25, either because on that day the Robigalia were celebrated, in honour of the god Robigus, for the prevention of the rust disease in grain, or the Serapia, a feast in honour of Serapis and related to the Egyptian grain. Graffiti of night-watchmen have also been found in barracks in Rome, in Trastevere. Their work in the sparsely lit streets was quite dangerous, as can be deduced from texts such as "All was safe", and the apparent need for support by the divine Emperors.

Portrait of Caracalla in the Capitoline Museums.

Photo: Jan Theo Bakker.

A thin wooden partition wall created an anteroom. Here some horses and the Dioscures were depicted. In the shrine proper is an altar, in front of some niches. On the floor is a black-and-white mosaic of a person who is about to kill a sacrificial animal. Parallels for this figure are found in the shrine for the Imperial cult in the Barracks of the Fire Brigade. On the right wall, next to Silvanus, are the scanty remains of a figure with a lance or sceptre. On the left wall we see a whole row of figures: Augustus, Harpocrates, Isis, Fortuna, Annona (the personification of the food supply), a figure with a cornucopiae (a Genius?), and Alexander the Great. From the location of Calpurnius' second graffito can be deduced that all these figures had been painted before April 25, 215 AD.

Watercolour of the row of figures: Augustus, Harpocrates, Isis, Fortuna, Annona, a Genius?, Alexander the Great. Image: Parco Archeologico di Ostia.

The figures are to be understood as follows. Augustus and Alexander the Great are present as illustrious predecessors of the Emperor, Caracalla, son of Septimius Severus. In 214 AD, at the age of 26, he had left for Egypt. During his journey he started to compare himself with Alexander the Great, as described by ancient historians. He ordered that throughout the Empire depictions should be made that presented him as a new Alexander. The Ostian bakers obeyed. They also thanked the Emperor for his distributions of free grain, personified by Annona. Isis (here, as so often, associated with Fortuna) and the child-god Harpocrates refer to the large quantities of grain that were imported from Egypt, which was an Imperial domain. The Dioscures were worshipped in Ostia as protectors of shipping, in this shrine as protectors of the grain fleet that transported the grain from Alexandria to Ostia and Portus.

Distributions of free grain

Each month 150.000 to 200.000 inhabitants of Rome received five measures of grain, a gift by the Emperor. This was not a system of relief for the poor, but a way for the Emperor to strengthen his ties with the populace. So far few historians have wondered how bread was made of this grain. It seems out of the question however that the recipients, often living in rented apartments, made their own bread, if only because of the fire hazard. The recipients could of course have made their own arrangements with bakers or people operating ovens, but this does not seem to have been the case. The Dutch legal scholar Sirks has shown that the Emperor entered into contracts with bakers for the processing of the free grain. The bread in Juvenalis' famous sneer "bread and circuses" (Satires X, 81) is to be taken literally, it is not a poetic description of grain: the Emperor did not leave the milling and baking to the recipients of free grain.

Originally the Emperor had to draw up contracts with individual bakers, such as Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, whose enigmatic tomb - quite possibly a folly - can still be seen outside the Porta Maggiore in Rome. Trajan simplified the system and gave the guild (collegium) of the bakers in Rome the status of body (corpus). From now on a single contract with the bakers sufficed. When a member of the guild operated a bakery for the processing of the free grain, and if that bakery met certain minimum requirements, he would receive certain benefits, comparable to our tax benefits. The grain was taken to warehouses owned by the Emperor - either by the recipients themselves or by porters -, and here the bakers collected it. The recipients paid to the baker a fixed amount for the milling and baking, but nothing for the grain. In other words: they received cheap bread, rather than free grain. Arrangements must also have been made for the Imperial personnel.

As to Ostia: it is the only city other than Rome in the western half of the empire in which a corpus of bakers is documented. What was the motivation here? Many Imperial slaves worked in the harbour, and fire fighters from Rome were stationed in the Barracks of the Fire Brigade (our Calpurnius was one of them). Presumably the Ostian guild baked bread for these people, on the basis of contracts with the Emperor. However, the supposed number of people served by the Great Warehouse and the surrounding bakeries, 10.000 to 14.000, implies an extremely high number of Imperial personnel in Ostia. Also, the location of the Great Warehouse and the dependent bakeries is difficult to understand if we suppose that these buildings supplied only Imperial personnel. The bakeries swept over the area near the Great Warehouse like a dark cloud. Such a development is easier to understand if the population of Ostia benefitted. There may have been distributions of free grain in Ostia as well, grain that was stored in the Imperial Great Warehouse, and processed by bakers who were members of the corpus.

Small millstones, stored in the Small Market (I,VIII,1). Photo: Jan Theo Bakker.