The Porticus of Placidia consisted of a series of rooms fronted by a colonnade, on top of the south mole of the basin of Claudius, so also along the right bank of the Fossa Traiana. It was the last monumental building of Portus.

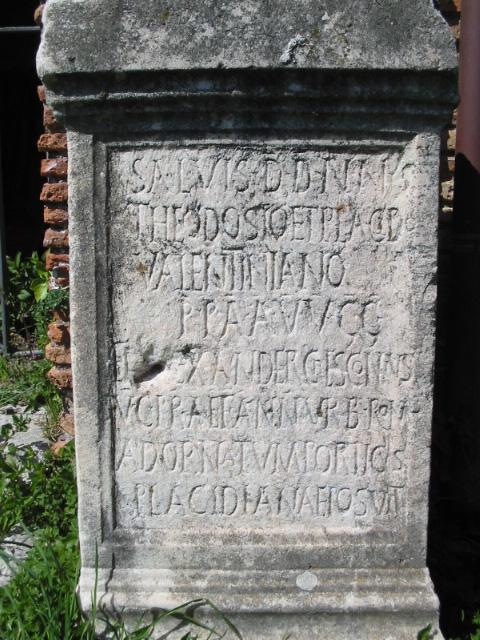

The name of the porticus is recorded in an inscription on a marble base for a statue that once decorated the porticus. The base was found between the ruins in 1822, as reported by Antonio Nibby.

SALVIS D D N NRIS (= dominis nostris)

THEODOSIO ET PLACIDO

VALENTINIANO

P P A A V V G G (= perpetuis Augustis)

FL(avius) [al]EXANDER CRESCONIVS

V(ir) C(larissimus) PRAEF(ectus) ANN(onae) VRB(is) ROM(ae)

AD ORNATVM PORTICVS

PLACIDIANAE POSVIT

For the well-being of our lords

Theodosius and Placidus

Valentinianus,

perpetual Augusti.

Flavius Alexander Cresconius,

most eminent man, Prefect of the Food Supply of Rome,

for the embellishment of the Porticus

Placidiana, placed this.Base of a statue from Portus.

H. 1.09, w. 0.54. Now in the Piccolo Mercato, Ostia.

EDR150107; LSA-1652. Photo: Jan Theo BakkerThe inscription is dedicated to Theodosius II, Emperor from 402 to 450 AD, and Placidus Valentinianus III, Emperor from 425 to 455 AD. The statue was erected by Flavius Alexander Cresconius, "Prefect of the Food Supply of the City of Rome, for the embellishment of the Porticus of Placidia" (Praefectus Annonae Urbis Romae, ad ornatum Porticus Placidianae). The porticus was therefore built (or refurbished and renamed) in honour of Galla Placidia, the mother of Valentinianus.

A fragment of a marble architrave was found together with the base. It has a double-sided inscription, of which only a few words have been preserved, mentioning the porticus. Also, the word "squalor" can be read.

[--- Porticu]M PLACIDIANAM [---]

[--- sq]VALORE [---]

[--- viro cl]ARISSIMO [---]

Fragment of a marble architrave.

H. 0.55. Current whereabouts unknown.

EDR150110 and 150111; EDCS-05700141.

Photo: EDCS.The ruins of the porticus can be seen on reconstructions from the 16th century.

The Porticus Placidiana on the reconstruction by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg from 1580.The ruins were described by Antonio Nibby in 1827. Translated from the Italian:

[Tabernae K] These extend over 600 meters, and occupy the back part of the harbour of Claudius: they are almost at a right angle with the axis of the harbour, and can be acknowledged as contemporaneous work; the construction of reticulate work and brickwork does not oppose that. Few traces remain of the tabernae themselves, but the plan remained intact until recent times, having been devastated last year and in the present year, to take advantage of the materials and use them in the construction of the new village, and to fill the palisades, which serve to regulate the flow of the river. Although today it is devastated, evidence remains that allows us to see that the nucleus was formed by large rectilinear boulders of Monte Verde tufa linked by travertine: few vestiges remain of the former; of the travertine stones, however, except some that have been sawn, and a few that have fallen, the others, although without support, still remain on the site supported by the quality of the cement.

This sequence of tabernae, or warehouses, is indicated by Du Perrach but with inaccuracy, between the communication channel of the Tiber with the harbour of Trajan, and the beginning of the mole: not knowing the angle that the harbour of Claudius makes with the harbour of Trajan, he placed these tabernae overwhelmingly towards the east, locating them behind the structures that belong to the harbour of Trajan. Behind this line of tabernae, towards the south, flows the canal of Portus, or the Fossa Traiana, which has a course running parallel with the Trajanic buildings, because it was made at the same time as those; but as soon as it approaches this ensemble, it makes an obtuse angle so as not to bump into them; this situation is a further confirmation of what was observed just now, namely that the tabernae being at right angles to the axis of the harbour of CIaudius must be ascribed to that; therefore, because they existed before the canal was dug, Trajan, to avoid them, had to twist it and give it an inclination towards the south-west, which without this necessity he had to avoid at all costs.

The Porticus Placidiana (K) on the plan by Luigi Canina from 1827.The remains were also investigated by Charles Texier in 1858. Translated from the French:

Sources

In the extension of the line of warehouses, one notices along the bank of the Tiber a solid construction of travertine and blockings, the length of which is 537 m. It seems clear that this work was undertaken a long time after the foundation of the harbour, to drive away from the entrance the sand carried by the river.

Deep and extensive excavations were carried out in this place, when the church of Fiumicino was built [the Chiesa di Santa Maria Porto della Salute, built 1823-1828?]; it is, so to speak, the main quarry that furnished the stones for the new building. We cannot judge today the state in which the ruins of this construction were found, but what remained in place still makes it possible to determine the main layout. The long trench, more than 500 meters, uncovered a series of large blocks or cubes of travertine, which measure approximately 1.25 x 1.25 m. and are 1 m. high; they are spaced 2.50 m. apart. These cubes serve as the foundation for a colonnade also made of travertine; but the shafts of the columns have almost all been removed; there are nevertheless a few left and we see that these columns were of the Doric order and have shafts with large protrusions like the monument called Aqua Claudia in Rome. At 8.26 m. behind this portico one recognizes a very thick blocking wall covered by reticulate work, and here and there the beginnings of partition walls, which allow us to suppose that shops or tabernae were established along the portico.

Because the entire excavation was carried out up to the level of the foundations of the portico, it is very difficult to recognize the details of this vast ensemble, which must have presented an admirable sight. An important point to make is that the masonry is far from being equally well executed throughout the length of the portico. Reticulate structures built with remarkable precision are succeeded by constructions of brick and tuff, and finally walls made with the remains of older materials. This tends to prove that this long portico was not built all at once, but that it was extended as the sand carried by the Tiber tended to invade the entrance to the harbour. One can see the canal running parallel to the portico 25 or 30 meters behind the big wall, but the sand has advanced so much that one has to travel more than two miles to reach the village of Fiumicino, built on the same bank, and this village is already no longer at the mouth of the river.

An inscription, the only one that has been saved, was found in the middle part of the portico, and is now in the courtyard of the castle of Ostia. It is a base of approximately 1.50 m. in height, which appears to have been intended to support a statue. It was consecrated by Alexander Crisconius, prefect of the Annona, and dedicated to the emperors Theodosius II and Valentinianus III, therefore perhaps related to the period between the years 423 and 450 AD, Theodosius having died that last year. [Texier now provides the text of the inscription] This inscription records a historical fact that could give the precise date of the monument. After the death of Honorius, in 423, his sister Placidia and Valentinianus are declared by Theodosius the Younger, the first Augusta and the second Caesar. It is probable that the prefect of the Annona, who had great authority in Ostia, wanted to honour this princess by giving her name to a work that was one of the most important in the city, since it owed its salvation to it.

This portico is located entirely outside the city, and we understand very well the reason for its creation; it had been built with the aim of keeping the sand carried by the Tiber away from the headland of the harbour, and as the deposits increased, the portico was lengthened. In the part closest to the dock platform, that is to say upstream, the travertine blocks are placed on a concrete mass composed of pebbles and crushed bricks; the longitudinal wall and the partition walls, which formed the tabernae or shops, are in opus reticulatum made with red tuff, and lapis tiburtinus, which is extracted from the nearby quarries of Tivoli; while the masonry of the part downstream is made of thick bricks all cemented, and the masses of travertine which carried the columns are established on an artificial surface, composed of debris of all kinds, even carved marble.

These constructions seem contemporaneous with the last repairs that were made to the lighthouse, and would therefore date from the beginning of the fourth century. From the moment one stopped extending the portico, or rather the river jetty, which halted the sands, the alluvium was carried by the sea current which ascends from south to north, and it did not take a great number of years before they reached the headland. It is then that the jetty will have been built which joins the island of the lighthouse to the mole on the right, the last attempt made to stop the silting up of the harbour of Claudius.

It is undeniable in fact, that in the soundings which are made between the point of the mole on the right and the solid mass of the island, a resistance is found in the subsoil that indicates works of masonry; in all other parts the probe easily penetrates to very great depths. We observe a bed of topsoil that is nearly a meter thick; it is formed from the detritus of plants and reeds that have grown for 1500 years; below is a bed of sea sand that is not higher than two or three meters; next one arrives at a mud bank of unknown height. It will be easy, from the data which exist, to establish the progress of the alluviums; we will make that the subject of a special study.Nibby 1827, 55-56, 78-80; Texier 1858, 36-40; Lanciani 1868, 182-183; Lugli-Filibeck 1935, 119-121; Meiggs 1973, 169.