This complex of buildings was situated on a narrow stretch of land between the basins of Claudius and Trajan, to the north-west of the latter basin (side VI of Trajan's hexagon). It may indeed have been an Imperial residence, perhaps normally used by the procurator of Portus, the supervisor of the harbour district.

The area with the Imperial Palace and the Terrace of Trajan (A), and the Amphitheatre (B). Map: Portus Project.The complex was behind the Terrace of Trajan, supported by a brick arcade resting on travertine corbels. As the name indicates, it has been assigned to the reign of Trajan. The west side is 210 m. long. The arcade creates vaulted recesses with back walls of opus reticulatum, for which small basalt blocks were used. A cryptoporticus runs immediately behind the facade along its western and probably also northern side.

The Terrace of Trajan. Photo: Portus Project.

The Terrace of Trajan. Photo: Portus Project.

The cryptoporticus behind the Terrace of Trajan. Photo: Portus Project.In the 16th century the remains were described by Antonio Labacco, and indicated on a plan by his son Mario. Translated from the Italian:

The building which is marked P was the habitation of the Governor. At present they call it the hundred columns (cento colonne). And I think that this name has been reserved because of the many remains of columns, which are seen underground. It is certain that this was a magistrate's place, because it is situated in the most beautiful place there is, and the height of the said palace surpassed all the other buildings, whence the ships could be seen entering the mouths of the port of Claudius up to that of Trajan. But because it is at present much damaged, and also very difficult to get to know, I have only placed a fantasy sign of it, because it is not possible to understand what it really was like.

The Imperial Palace (P) on a plan by Antonio and Mario Labacco from 1559. South is up.On a view of Portus by Georg Braun from 1580 the building is accompanied by the text Palatium Regium, quod a Traiano extructum putat ("Royal Palace, which is thought to have been erected by Trajan"). Some indistinct remains can be seen on the fresco of the remains of Portus by Ignazio Danti from 1582, now in the Galleria delle Carte Geografiche of the Vatican museums.

The Imperial Palace on a view by Georg Braun from 1580. South is up.Finds from 1794 were reported by Carlo Fea in 1802, apparently made during digging by Father Casini Somasco. Translated from the Italian:

The remains of a temple of Hercules were found in the aforementioned year 1794 at a small distance from the edge of the harbour, with his fragmented statue, and many remains of cornices, and other architectural elements. Four to five thousand pounds of a lead pipe, capable of six ounces of water, with an inscription of Messalina, found on the same occasion in an excavation made on the site on the left hand side between the Traianello [the hexagon of Trajan] and the Temple, with many ramifications, and underground at a shallow depth, somewhere in the middle of the sand, which seemed to indicate a garden, and bedrooms, leads one to believe that that Empress, taking advantage of her husband's gullibility here too, had fabricated some delights there. The statue of Hercules has not been identified. Only one statue of Hercules in the Museo Torlonia (Hercules holding his son Telephus) is said to have been found in Portus. Another statue of Hercules, composed of many pieces, fits better with the description "fragmented" (the Temple of Hercules will be mentioned again in 1868 by Rodolfo Lanciani, see below in his description).

The statue of Hercules holding Telephus.

Museo Torlonia, inv. nr. 388. Photo: P.E. Visconti 1884, Tav. XCVII.Statue of Hercules holding the Apples of the Hesperides.

Museo Torlonia, inv. nr. 25. Photo: Fondazione Torlonia.In 1827 Antonio Nibby suggested that the building is identical with a "palace called Progesta", mentioned in a description of the boundaries of the diocese of Portus from 1018 AD: ... usque ad locum qui Portus Traiani vocatur, et usque ad Palatium quod vocatur Progesta [or Praegesta], et usque ad Civitatem ipsam vetustissimam cum lacu Traiani ("... up to the place that is called Portus Traiani, and up to the Palace called Progesta, and up to the very old City itself with the lake of Trajan"). The position of the property in the list suggests that it lay between the two harbours (progesta is from progero, "to bear or carry in front"). Some ruins are depicted on a plan by Luigi Canina, also from 1827. A reconstructed plan was made by Pierre-Joseph Garrez in 1835.

The Imperial Palace (to the right of Q) on a plan by Luigi Canina from 1827.

The Imperial Palace on a reconstructed plan by Pierre-Joseph Garrez from 1835.A detailed desciption of explorations in the complex was published by Texier in 1858, accompanied by a general plan, and by views and plans of the ground floor and a cistern. He calls the building the Palace of the Prefect of the Fleet. Translated from the French:

The side of the hexagonal harbour that faces the north-east is occupied by several hills covered with bushes, but which only show above ground incoherent debris of walls and ruins. I had in vain examined how this massive whole could be linked to the entire site, and nothing put me on the way to its original function, when a fortuitous event came to open a new path to my investigations. A workman employed in the excavations had pursued a badger which had slipped into a sort of burrow; the workman tried to reach it with a stake, but instead of entering a narrow conduit, he found that the stake went into a deep hole and could turn in all directions in the void. I was called and recognized indeed that this hole communicated with a large vault. Paper and dry grass lit and thrown into this hole did indeed light up a room which seemed immense to us; sounding its depth with a rope we found nearly four meters. It would not have been prudent to venture immediately into these unknown paths; the orifice was cleared to give air; but as all the flaming matter that had been thrown into the hole had burned peacefully, we had nothing to fear from the toxic air.

It was not without difficulty, however, that we succeeded in descending into this subterranean room; candles had been brought from Fiumicino, and we understood that this place had for centuries been untouched by human footsteps. Lianas and stalactites hung from the roof, small pools of water glistened in the depths, and the ground was composed of a black and fine compost. Going around this room, which was oblong, we recognized several doors perfectly free of earth and rubble, which led to other rooms, and galleries which seemed even larger to us, in the almost complete darkness in which we found ourselves. After having attached a rope to the entrance hall, the workers traversed this new labyrinth without finding the end. Every day a few new rooms were reported; they were all intact, perfectly empty, and nowhere was there any communication with the outside air.

To describe the surprise I felt on entering this underground building would be impossible for me. The arrangement of the rooms seemed to me so bizarre that I could not suspect what purpose they had been used for. We sometimes found ourselves stopped by a network of long roots which formed a veritable fabric; they were the roots of the trees which covered the ground, and which, penetrating into this void, had taken on an extraordinary development. We saw them crawling on the walls and going to seek, sometimes very far, an interstice where they could find a little topsoil. I often observed these movements which one could rightly attribute to vegetable intelligence; they had to be very singular to divert my attention from the main object of my subterranean peregrinations.

The days passed with these visits, without my being able to obtain from the inspection of the ruins any clarification, any basis, to support my operations of reconstruction. It was then that I recognized the great advantage of compass bearings. Without this instrument it would have been impossible for me to determine in which direction I had wandered for so long. But, having taken the readings of the principal walls and the longest galleries, I understood that, the underground building following the two sides of the hexagon of the harbour of Trajan, it was already a step forward for tracing the direction above ground.

I had already understood during my incessant visits that this multiplicity of rooms could only belong to a palace. I had seen cisterns, chimneys with heating pipes, several substructures that were part of an atrium, but I could not yet fathom on which floor of the building I was: was it the ground floor or basement? The long stay of several people in these vaults with lights was beginning to pollute the air; moreover, a sour and nauseous odour was spreading, the origin of which I could not work out, and which the workers attributed to the presence of snakes, which hardly encouraged them to venture further; but on the other hand the hope of discovering some antiquities outweighed their fear, so that it did not take much trouble to get them back to work. The badger hole had been marked with a stake and a pavilion, it was our only landmark outside. It was absolutely necessary to provide air to our vaults by breaking through in some favourable place. Eventually I traced on the ground the course of a long gallery whose wall contained regular depressions, which seemed to me to have been windows or ventilation shafts. An excavation carried out at the presumed extremity of this gallery had all the desirable success. We went straight into the underground rooms, which were airy and could be walked through without fear of being suffocated.

Called back to Rome by the need to build instruments to draw the overall plan, I shared my discovery with a large number of artists and lovers of antiquities, who expressed the desire to visit these ruins. A festarolo of Saint Peter took care of lighting them very brightly, the Trattoria della Lepre transported its crockery and its gnocchi famosi there, to serve a feast to the visitors. The Fiumicino boats provided the tables and the benches; several loads of fiaccole or large lanterns which serve for the illumination of the cupola were transported to Ostia, and placed in each of the rooms so that they could be traversed at leisure. They began by exploring the ruins of Ostia, where the climate seemed less unhealthy since the Roman cooks had settled there. Finally they rested and sat down at the tables in the subterranean galleries. The visitors were far from suspecting that they were about to see the horrors of Phineus' feasts repeated [Phineus is a mythological figure who set a trap with a meal and the Harpies].

No sooner had they been seated than a sharp, strident, prolonged cry was heard in the depths of the galleries; everyone listened, surprised by these unknown noises which resembled the whistling of the wind through the badly joined doors. Soon black and velvety veils appeared to sweep the faces of the frightened guests; some left their places to flee, others wanted to understand the unexpected movement that was taking place in the heights of the vaults. There were thousands of bats which, awakened by the heat and the light of the lanterns, came in incalculable numbers to throw themselves on the table which was better lit than the rest, were going to burn themselves and fry in the grease of the lanterns, or fall dying on the feast dishes. Never could the harpies entering the palace of the king of Thrace cause such terror; before everyone could identify the cause of this noise, all the rooms were invaded by these nocturnal animals; the black masses which hung from the vaults and which at first appeared like inert heaps of earth and dust, began to stir and dissolve; they were agglomerations of bats whose wingspan seemed enormous, and which in reality were no less than twenty-five centimeters. The genus belonged to the species named spearhead, vespertilio hastatus. Each of the assistants had only been able to escape the impure contact of these new Harpies by a flight surrounded by a thousand obstacles. Thus ended the first visit to the ruins of the old palace.

A superstitious Italian and jettatore [bringer of misfortune], the Chevalier of Castel-Nuovo [in Naples], pointed out that we received just punishment for our misdeeds by wanting to devote to frivolous pleasures the venerable remains of antiquity which only deserved our respect; but a Neapolitan architect thought that all this misadventure was due to the presence in our company of a jettatore, like the Chevalier de Castel-Nuovo. I have never been able to find out which of the two reasons was the right one. When, recovered from our surprise, we tried a few days later to clear certain rooms, we noted that the ground raised by several feet was only composed of the droppings of these bats, which obviously had chosen these underground dwellings for several centuries as their den.

To describe in an intelligible way these remarkable ruins, let us suppose them completely cleared and accessible from all sides. We will take for our route the general plan which was created with the compass with incalculable difficulties, and restored to the surface of the ground, so as to understand the entirety and the extent of the building.

The palace, the ruins of which were unearthed in such an unusual manner, was situated between the two harbours of Claudius and Trajan; its entrance faced the harbour of Claudius, and therefore looked out to sea. One arrived under a portico composed of five arcades which gave access to as many rooms, the walls of which are still covered with stucco. From there one entered an atrium 15 m. long and 9 m. 60 wide, in the middle of which is a cistern. Two large chambers, which were framed only by two pilasters (and probably by two columns on the first floor), opened to the right and left of the atrium. The back part of the building was occupied by six rooms; the entire gallery that surrounds the atrium is barrel-vaulted with openings. To the left of the entrance to the portico are six large rooms in two rows, the vaults of which take on various forms; the front rooms are pierced with windows; the rooms in the second row open onto a long gallery which communicates at its end with the first room with pilasters. Assuming a similar layout on the other side of the portico, we find in this group a majestic arrangement for the entrance to a large palace.

I have reason to suppose that the rooms which I have just described belonged to the basement, firstly because they are lighted only by very narrow windows, then because the walls are covered with a rather coarse stucco, which however had received some painted decoration. The masonry of all these constructions, which appears at certain intervals under the coating, is made of concrete and reticulate work, assembled with rare precision, and indicating the good times of Roman architecture. One of the curiosities of these constructions is the varied arrangement of the vaults, which are different in all the rooms. I must add that the ensemble of all the chambers which I have just described is at right angles, while the body of the building which I am about to examine forms with the first an angle of 120 degrees, which is that of a regular hexagon. Now, as the direction of the walls of the first palace is parallel to the north side of the harbour, the direction of the second body of the building is parallel to the second side, that is to say that the palace embraced two sides of the hexagonal basin. This layout suffices to indicate that the second building which concerns us is later than the foundation of the harbour of Trajan; one must even think, based on the nature of the materials which are assembled with infinite care, and recall the belle époque of Roman art, that this building was part of the overall plan designed by the Emperor Trajan.

The second body of the building also seemed to have been intended for housing, but its layout is entirely different. On the side which looks out to the harbour of Claudius is a long gallery of more than 50 m. in length and a width of 2 m. 10 c. On the front wall one observes a series of niches, twenty of which still exist and which are equally spaced. These niches communicate with vertical channels that could lead to the supposition that they are chimneys, if they were not so numerous. Besides, we will see the heating system in another room. But these channels which are square seem to me to have no other purpose than to provide air and a little light to that gallery, which was obviously below the ground. All along the front wall runs a bench in masonry, the purpose of which does not seem very clear to me; perhaps one would find by digging along the bench a channel which would join the aqueduct of Ostia, and this gallery would be intended only for the water supply.

All the rooms which are at the level of the gallery therefore formed cellars and substructures; the entrance to the body of the building can be recognized by a triple door, opening onto a room common to the two palaces which communicated through a corridor. In the rooms to the left of the entrance, one observes chimneys or hypocausts built exactly like those of the Baths; they are inserted into the wall at a certain height above the ground, there is a high fireplace, and heating pipes which go up to the upper floors. The construction of the vaults is very simple, in spite of their apparent complexity. In the collapsed parts we see that they were made entirely of concrete; the curvature and the shapes were made of wood, and on top of that the concrete was poured which was customized by tamping; when the mass was dry, the moulds were removed and the vault was finished. Concrete constructions have lately been mentioned as a modern discovery; we see once more that, with respect to constructions, the ancients left us little to innovate. Below each atrium are cisterns which are still in an astonishing state of preservation, but it is not so easy to understand the function of a large number of oblique rooms, recesses, and dead ends, which make these ruins one of the most curious parts of the ancient Port city.

The research and study of this building occupied me for more than a month, during which a good number of curious people came to visit it; but since that time I haven't heard of it again, perhaps the entrance was again blocked by rubble and vegetation. As I published nothing on this subject, and as the population of artists then in Rome was liable to disperse, it is not surprising that these ancient ruins fell into oblivion. I have vainly sought in the modern authors who have written on the city of Ostia some indications of the time when the first discovery of these ruins, or rather of the long gallery, was made, because it is only there that I observed some traces of visits. Bergier Danville, Pirro Ligorio, and travelers who are not special, but who spoke of these ruins, like Father Labat, etc., none of them provided me with the slightest explanation.

[Texier then quotes Carlo Fea's description of the discovery of the Temple of Hercules and the stamp of Messalina, without knowing his name. He continues:] The indication of the place agrees fairly well with the location of the palace, but that is all that can be said. According to the state of the stuccos which cover the major part of these walls, one can conjecture that the rooms were little inhabited, because the flower of the coating is found almost everywhere. There was no trace of modern visits, except at the entrance to the long gallery, where I thought I read the date 1764; it is not probable that all the rooms would have been visited in our time before I entered them.

Although nothing can serve to specify the function of this building, we can assume with reason that it served as the residence of the supreme magistrate who administered the city and the port. We find in the other parts of the enclosure all the public establishments which may be necessary in a large military arsenal, the castrum, the warehouses for parts of the rigging, the warehouses for grain and merchandise, the naumachia to exercise the sailors, finally the baths, bazaars, temples and civil dwellings, which we are going to deal with. This palace would also have served as the Emperor's residence during his visits to Ostia; but we only know the substructures. It is probable that if one excavated in the upper part, and the plan would be a certain guide, one would find numerous remains of the decoration of the building.

The Imperial Palace (E) on the general plan by Charles Texier (1858). South is up.

Plans and views of the subterranean level and a cistern of the Imperial Palace by Charles Texier (1858).In 1864 the building was searched further by prince Alessandro Torlonia. The first report was published by F. Lanci, in the same year:

The approaching summer season suspended the excavations that His Excellency Prince Torlonia has undertaken at his estate of Porto; this however with the intention of starting them again next autumn. In the last phases of the excavations the work was directed to the place where the palace of Claudius was found, and the atrium with niches was discovered, in front of two of which were lying two statues of an exquisite chisel, one nine and a half palms high [2.12 m.], apparently representing a Muse, the other ten palms high [2.23 m.], and depicting an Aesculapius. Both, whole except for one hand and some small accessories, have already been taken to Rome, and bear witness to perfect craftsmanship. These excavations, given the short time they lasted, can be considered very successful, because they brought back to light the magnificent torso of an athlete, half the figure of Septimius Severus, the fragmented Leda, but without missing a part, a philosopher and a slave of rough work, a small Aesculapius and the famous bas-relief representing the Trajanic port, of which a summary account has already been given [by G. Henzen]. Now we must add to the finds the two statues, of which mention is made at the beginning, and several columns, both large and small, of very beautiful marble. From the continuation of such excavations a good harvest of beautiful finds is to be expected. Unfortunately the text is rather vague about the places of discovery. Were all these statues found in the Imperial Palace? Only one statue of Aesculapius in the Museo Torlonia is said to have been found in Portus. It has the reported height. The only statue of a Muse with the reported height is of Melpomene, Muse of Tragedy.

The statue of Aesculapius. H. 2.20.

Museo Torlonia, inv. nr. 94. Photo: P.E. Visconti 1884, Tav. XXIV.Statue of Melpomene. H. 2.10.

Museo Torlonia, inv. nr. 301. Photo: P.E. Visconti 1884, Tav. LXXVI.Rodolfo Lanciani visited the site shortly afterwards, on 22 May 1866. He has left us a fairly detailed description, published in 1868, in which he introduces the name Palazzo Imperiale for the complex. Translated from the Italian:

In the most central and most beautiful position of the city, that is on the peninsula that separates the harbour of Claudius from that of Trajan, are imposing ruins superior to all the others in terms of height and extension, and therefore more than the others studied by antiquarians. [Lanciani then mentions the earlier descriptions and continues:] The recent excavations have resolved this very important question for the topography of Portus: they have shown us an imperial palace of great magnificence and extension including in its perimeter baths, atriums, porticoes, temples, gardens and even a theatre; very few traces of which monuments appear in my plan, not having had the good fortune to be present at the excavations which were soon covered over in such a way as to make any topographical survey impossible. Nonetheless, here is some news that I was able to gather on the spot.

The imperial palace is bounded to the north by a small road which divides it from the warehouses, to the east by the harbour of Trajan, to the south by another path which separates it from the forum, and to the west by the harbour of Claudius. Almost the entire surface was excavated in the 1864-67 working seasons, and my guide (May 22, 1866) was unable to express the admiration felt at the sight of such imposing buildings. The main decoration of the building consisted of a very long portico of columns placed on the side of the harbour of Claudius, along which the main apartments were connected. The portico appeared arranged in this way: at a height of 2.50 m. above the current water level of the marsh large travertine corbels project from the facade wall for about 0.60 m., on which arches are resting with a diameter of 3 m. An elegant brick cornice protrudes for 0.22 m. on top of the arches, above which the parapet of the terrace must have risen, now almost totally destroyed. The general line of the building is interrupted from time to time by small towers that jut out for 3 m. Beyond the parapet runs the street, or terrace, 6 m. wide, below which is a corresponding very long corridor, which we will discuss below. In the masonry of the vault, they assured me, was a conduit without inscription of about 0.15 in diameter, which later changed its course in the direction of the marine baths.

On the side of the terrace opposite the parapet rose the portico with columns, the bases of which were found mostly in place, while the shafts lay broken on the ground. Perhaps due to the better-preserved remains of this portico, the denomination of palace of the hundred columns ("palazzo delle cento colonne") preserved by Labacco arose in the past centuries. The brick front of the building was situated about 3 m. from the middle of the columns and was interrupted by doors corresponding to the main rooms, on the arrangement of which I have been able to gather the following information:

Starting from the south facade of the building and following the direction of the portico, traces of a quadrangular room terminated by an apse can still be seen on the terrain: that is, it repeats in smaller proportions the shape of the basilica adjacent to the imperial palace on the Palatine; and perhaps its function was similar. From the story of the excavators it seems that it had a mosaic floor, and representing a centauromachy. About four rooms later the same men pointed out to me a large hall with semicircular apses on the sides, and decorated with niches and columns in cipollino: perhaps it was a bathing room, if it is true that it had a floor of marble slabs and was enclosed by steps with heating provisions and hypocausts underneath. Close by this was followed by a circular room called by my guide a temple, after which it seems that an arrangement similar to the one described up to now was repeated. [Lanciani then mentions the report by Lanci and continues:] Also the temple of Hercules enclosed in the perimeter of the palace was again excavated last March [so in 1867], extracting drums of columns, finely carved capitals and three bases of 0.90 m. in diameter [later Lanciani says that a statue of Hercules, reduced to fragments yet almost entirely recomposed, was found near the presumed Barracks of the Fire Fighters, much further to the south].

The most important discovery is that of the theater existing within the same limits of the palace, not otherwise than in the Neronian one of Anzio. I don't believe it has yet been excavated, but the traces existing above the ground are so evident that I cannot explain how it has been able to escape the attention of archaeologists and especially of Canina and Texier until now. Although of mediocre proportions, the imperial theater of Portus is in all respects similar to the analogous ancient buildings: part of the scaena decorated with niches survives, and part of the substructures of the cunei, which, as is normally the case in Greek theatres, do not converge in the centre of the scaena, but at a point which is some meters in front. Behind the same scaena emerged a perfectly preserved stairway, but completely covered by lianas and brambles, after descending which with no mean effort we found a small passage with only one door on the left: but the rubble, almost reaching the archivolt, made it impossible for us to penetrate further: on the other hand, the perfect ventilation of the place offered us the possibility of penetrating those subterranean rooms from another side. And so it happened, having come across an opening half flooded by the swamp and a hundred meters away from the stairway described above, by means of which we had access to a veritable labyrinth of underground halls and corridors, the extent of which is impossible to determine, most of it being invaded by water, encumbered by rubble, without light and almost without air. Without going into minute details, I will observe the following about these subterranean rooms:

1. There are currently no less than 35 practicable rooms and corridors. I do not give a description nor a plan, because both have already been published by Texier in the work quoted several times which has come into my hands only in the last few days, after he had completed both with considerable effort. In the plan provided by the famous topographer some large rooms appear, in which, despite repeated attempts, it was impossible for me to penetrate: so I also don't recall having found traces either of the heating system or of the paintings he observed.

2. The nature of the walls is partly reticulate, partly brickwork of truly incredible perfection and such that I doubt it can be found in any other ancient building.

3. A large part of the walls and especially the vaults are covered with fine plaster. I have not seen any graffiti, apart from some numbers.

4. Each of the rooms originally received light and air from some slit windows, 0.65 high, 0.14 wide, occurring both in internal courtyards and along the exterior facade. Starting from this situation, Texier wanted to deduce the plan of the upper floor of the building from that of the underground area: but recent excavations have shown that the layout of the walls is very different on one floor and on the other: and this without any harm to the solidity of the building, since the thickness of the walls and vaults of the underground area is such that on the solid and uniform foundation formed by them, the architect could without fear raise walls with a different plan. Only a long corresponding corridor was found below the portico with columns mentioned above.

It remains to determine the author and the time of construction of the imperial palace. First of all, it should be noted that the whole of the subterranean substructures constitutes two parts of a building placed under an angle of 120 degrees: that is, parallel to two consecutive sides of Trajan's hexagon: which indicates that the building is either contemporary or later than the establishment of the harbour. But other documents clarify the question even better. Here are two fragments of inscriptions I saw among the ruins of the palace:

both with the date of the sixth consulate of Trajan, that is of the year 112 AD. Now although most of the coins of that prince with the inscription PORTVM TRAIANI SC have his fifth consulate, there are also authentic specimens with the date of the VI, a diversity which I believe is related to the duration of the work on the port which began perhaps in 103 and was completed around 112. It therefore appears that as soon as the work required by the needs of navigation was completed, the construction of the imperial palace began. Stamps extracted from its ruins confirm this fact. Here are the main ones: [discussion of brick stamps from 114, 115 and 116 AD]. Some restorations of the palace must have been carried out during the reign of Hadrian, according to the following stamps also found there: [discussion of brick stamps from 123 AD]. The palace received new and more important embellishments under the Antonines, especially in the southern part where I have found many examples of the following stamps: [discussion of brick stamps from 144, 154 and c. 157 AD].

...TRAIAN...

...VI COS DE......TRAIANO

...NT MAX

...cosVI.PP

...NI.FELIC

The Imperial Palace on the plan of Rodolfo Lanciani, who was assisted by Luigi Crostarosa, from 1868.The area was cleaned by Guido Calza in 1925. Translated from the Italian:

[In the north-east part of the complex] Just below the ground level, an open hollow in the ground revealed a latrine whose seats consisted of a horizontal slab (2.00 x 0.60 m.) with three equidistant openings, in front of which is placed vertically a second slab with as many holes matching the first ones. The slabs are evidently adapted to this use; the walls of the drainage sewer are in opus listatum (small tufa blocks and bricks).

[In the north-west part of the complex] The cleaning of the ruins has revealed some ambulatories of the small theater of the so-called Imperial Palace. In front of these is a wall with a small central niche (perhaps the scaena or a room behind it). Behind this wall a stairway descends to the lower floor, and preserves the vault of the second flight; the construction is in good Hadrianic opus mxtum.

[In the south-west part of the complex] It is a complex of very interesting ruins that the cleaning of the ground has brought to light, and which also attract the visitor's curiosity in terms of aesthetics. In fact, at this point, that is at the north-west corner of the basin, having had to make a drainage channel, it was possible to see the foundations of a group of rooms belonging to the so-called Imperial Palace. We have entered a large room with a rampant vault paved with bipedal bricks and plastered in the first section with a waterproof plaster and on the upper part and in the vault with a fine white plaster. The walls of the room are of opus mixtum. In the masonry of the vault is a sewer covered with flat tiles which, following the inclination of the vault, flows into a second sewer perpendicular to this one and created in the masonry formed by the meeting of two vaults and covered by two superimposed large tiles. The sewers measure 0.80 x 0.50 m.

This room is followed by another, covered by a concrete vault, built on a support dug into the ground (with a thickness of 85 cm.); in this room there is no trace of plaster. Above this vault the current trench has revealed the presence of a system of suspensurae with square pillars (60 by 22 cm.) and a floor with two rows of large tiles and cocciopesto. The room is six meters wide: in one wall there is a vent for the passage of heat to other rooms. This group of bathing rooms bordering the horrea was heated by openings of furnaces created in the last section of a gallery on the west side of the so-called Imperial Palace.

This gallery, which is visible and practicable also in other points, forms the perimeter towards the harbour of Claudius of the so-called Imperial Palace. It is a gallery 2.05 m. wide, covered by a concrete vault, in which the entrances to large underground rooms open, and which is ventilated and illuminated by well-shaped skylights, placed at a distance from 3.20 to 4.20. These skylights have the opening in the wall at the height of the upper gallery, and the drawing [see the figure below] shows their singular shape: after a vertical stretch of 80 cm. they open towards the inside of the gallery forming a small window 1.10 m. high and 85 cm. wide, slightly splayed on all sides. To prevent rainwater penetrating from the upper opening of these skylights from falling into the gallery, they all end up in a sewer created in the wall itself, which collects the water of them all.

The external facade of this gallery, made of opus mixtum of basalt blocks and bricks, is decorated by a continuous balcony supported by travertine corbels 2.30 m. apart on which the vault was built (a common type in Ostia). A terracotta cornice formed by three protruding bricks serves as a crowning feature. In front of this balcony wall is a platform 2.50 m. wide, made of calcestruzzo di selci. Very late, other walls in opus listatum lean against this construction from the Trajanic period. On the wall that divides the corridor from the rooms at the height of the level of the gallery, three travertine parallelepipeds were found which must have been the bases of a colonnade still visible in recent times, when this complex of ruins was called the palace of a hundred columns.

Drawing accompanying the description by Guido Calza. NSC 1925, 67 fig. 8.The building was discussed again by Giuseppe Lugli in 1935, using a plan made by Italo Gismondi. Translated from the Italian:

[Structure at the south end - 25] Lanciani draws in this point a long and narrow building that looks like a portico, overlooking the Trajanic basin; at present nothing can be distinguished on the ground other than an oblong mound with some transverse walls suggesting warehouses. The signs of previous excavations appear everywhere. After n. 25, along the edge of the basin nothing more can be seen, everything being razed to the ground.

Further back, the cut made for a cart road has exposed an area of tuff and brick flakes, with walls of tuff and bricks of a late period; then a large quantity of tiles for 30-40 meters, among which numerous yellow sesquipedal bricks with a thickness of 4-6 cm. can be seen, which would appear to be of the period of Claudius.

[Terrace of Trajan - 12-13] How things were on this side at the time of Claudius we do not know: certainly large quays had to be developed here for the mooring of ships, this being the most suitable point for this purpose due to its proximity to the hinterland. When Trajan built the new port, these quays were no longer needed and so he brought the pier forward, building the present building on top of it and embanking it on the west (n. 12) and north-west (n. 13) sides with a hanging terrace more than 200 meters long.

The terrace is made up of many brick arches resting on travertine consoles; the back wall, which had to resist the beating of the waves, was made of opus reticulatum of basalt, well cemented. On the arches ran a hanging balcony, paved with white mosaic, and in the back part was a portico with arches and pillars belonging to building n. 13.

The north-west side (13), although covered by much vegetation, can be recognized well along its entire length; in various places it was reinforced in the time of Constantine when the city wall was built above it. Towers were then set against it, one of which appears at the corner between the two, in the trench made recently to provide an opening for the corridor behind side 12. In fact, the solid foundation nucleus can be seen, with the surface at a higher level, made of a poor brick facing from the beginning of the 4th century; the same facing covers all the walls on side 13. It was not considered necessary to erect the wall on the western front facing the sea.

Let us examine the interior of the building. The lower floor remains entirely closed and consists of two long parallel corridors, one just 1.20 m. wide and isolated, behind the facade wall, and the other, larger one (about 6 m. wide) treated as a cryptoporticus, for use as a transition to warehouses of the port.

The first corridor, which we will call a service area, shows a difference in construction, as it has the west wall, that is the external counter-wall, founded over a meter higher than the east wall, and therefore has an exposed foundation, and the rest with a brick facing; while the opposite wall presents itself from the floor level in opus mixtum of reticulate and bricks. A barrel vault covered both.

High up in the west wall are numerous slits for the light and since in the event of a storm the water entered through them, a channel was left in the wall which transported this water and that of the upper terrace, leading it back into the sea.

The large cryptoporticus is divided into many segments with cross vaults and is closed at both ends: it provides access to some rooms towards the east and north, these too semi-subterranean, where the most beautiful Trajanic facing of all the port buildings can be seen, with remains of plaster.

Given the position and configuration of the building, it does not appear to be a warehouse for foodstuffs, but rather a place for resale, a market, equipped with a certain refinement, so as to provide visitors with diversion and rest. Various staircases lead to the upper floor, on which remain numerous rooms and an exedra with remains of a black and white mosaic floor.

The Terrace of Trajan (nrs. 12-13) and the Imperial Palace (nrs. 25-27) on the plan by Italo Gismondi from 1933.

[Imperial Palace - 26-27] The many mounds of earth and the ditches that can be seen throughout this area are the only witnesses of the great excavations carried out between 1864 and 1867, excavations which yielded so much statuary material to the Torlonia Museum and made it possible to recognize the existence of large buildings such as "baths, atriums, porticoes, temples, gardens and even a theatre". Unfortunately today one only sees a few outcropping walls and towards the center a rectangular courtyard with tabernas around it, much lower than the ground level and filled with weeds.

[Lugli then summarizes Lanciani's description. He believes that all statues mentioned by Lanci were found here. He then suggests that we do not see an Imperial Palace, but the Forum of Portus, and continues:] Lanciani, among the forms conserved at the Royal Institute of Archeology (form n. 39489) provides the detailed plan of large baths [see the figure below], of which he does not specify the location; it was fronted by a large hemicycle and composed of numerous rooms with basins for hot and cold baths, interspersed with corridors and meeting rooms. It is very probable that it must be situated in this area.

A plan by Rodolfo Lanciani of baths. Lugli 1935, fig. 62.The Portus Project

The British-Italian Portus Project, directed by Simon Keay of the University of Southampton, carried out extensive geophysical research at the start of this century, with subsequent excavations of the buildings to the north-east, beginning in 2007.

Impression of part of the ruins. Photo: Portus Project.The west part of the complex was investigated with geophysics only. Here buildings 8.1 to 8.10 can be recognized. No evidence was seen in this part for the theatre mentioned by Lanciani. Many vaulted rooms and corridors still survive intact in this area. The project made a laser scan animation of some of the rooms (see Movies - The Portus Project).

Click to enlarge.

Plan with buildings 8.1 to 8.10 of the Imperial Palace. Keay et al. 2005, fig. 5.23.A first building on the site must have belonged to the reign of Claudius, witness the discovery in 1794 of lead waterpipes with the name of Messalina, Claudius' wife (EDR150283). The Portus Project unearthed a Claudian mole to the north of the complex. It is perforated by large holes for wooden beams. There seems to have been a lagoon to the south of the mole.

The Claudian mole. Photo: Portus Project.The complex was built at the end of the reign of Trajan or the beginning of the reign of Hadrian, with opus mixtum of excellent quality. Lanciani mentions brick stamps from the years 114-116 AD, and he saw two fragments of inscriptions mentioning Trajan; to the second inscription another fragment could later be added.

[---] TRAIAN(-) [---]

[--- imp(erator-)] VI COS DE[s(ignat-) VI ---][Imp(eratori) Caes(ari) Divi Nervae f(ilio) Nervae] TRAIANO

[Aug(usto) Germ(anico) Dac(ico) Parth(ico) po]NT(ifici) MAX(imo)

[trib(unicia) pot(estate) --- imp(eratori) --- co(n)s(uli)] VI P(atri) P(atriae)

[--- port]VS TRAIANI FELICISMarble slab, disappeared.

111 AD. CIL XIV, 89; EDR149994.Marble slab, now in Rome, Villa Albani-Torlonia.

112-117 AD. CIL XIV, 90; EDR093994.

Opus mixtum in the interior of the Palazzo Imperiale. Photo: Portus Project.In this period a second mole was added to the south of the Claudian mole, with a perpendicular mole, creating a small dock with an entrance that was about 25 m. wide. To the west of the dock buildings 1 and 3 were erected, with vaulted rooms and cisterns. Building 1 had at least three storeys and was most likely a castellum aquae, a central distributing group of cisterns. The ground floor has a series of vaults and windows. It was not used for storing water. The first floor has a large and a small cistern, lined with the waterproof opus signinum. Not much is preserved of the second floor, where opus signinum can also be seen. Building 3 had at least two storeys. It had a central courtyard surrounded by a vaulted corridor. The floors were of simple opus spicatum (bricks in a herringbone pattern). In a later period a glass-making workshop was established inside.

The Imperial Palace and the buildings to the east. Plan: Portus Project.

Building 1. Photo: Portus Project.

The interior of building 1, ground floor. Photo: Portus Project.

The interior of building 1, small cistern. Photo: Portus Project.To the same period belongs building 5, identified as shipsheds or navalia (building 7 also formed part of it; this building is discussed separately). On the north side of building 5 ran an aqueduct from east to west, with brick piers measuring 3 x 3 m.

In the Hadrianic period building 2 was added, with brick stamps from 122-123 and 134 AD. It had at least two storeys. On the ground floor are two rooms with a barrel vault. The first floor was a single cistern. The various cisterns in the complex will have supplied rooms throughout the complex, but they may also have been used to provide fresh water for ships leaving Portus on their return journeys. Some work in the complex must also have taken place in the Antonine period: brick stamps were found from the years 144, 154 and c. 157 AD.

Building 2, cistern. Photo: Portus Project.To the south of buildings 1-3 was an open area. In the first half of the third century (a date indicated by ceramics) building 4 was erected here. It consisted of two concentric ovals, giving it the shape of an amphitheatre. The long axis measured 43 m., the short axis 38 m. The gap between the ovals is 3 m. At the east end of the long axis is a small, square chamber. There were no radial walls between the ovals, so seating banks were perhaps made of wood. At the west end was part of a third oval wall, apparently a hemicycle that supported a colonnade. The structure might well be visible on the plan of baths made by Lanciani and published by Lugli.

The amphitheatre-shaped building 4, plan of the excavations. Keay et al. 2013, fig. 14.10.

The amphitheatre-shaped building 4. Photo: Portus Project.It is by no means certain that gladiatorial combats took place in the building. The excavators have suggested that it may also have been a place where the procurator addressed the people who worked in the palace or people who worked in the port, or a place for them to communicate verbally. Yet another possibility would be that the arena was flooded by the nearby cisterns, and that mock sea battles with small boats (naumachiae) were held here. However, the presence in Portus of a building used for gladiatorial combats had already been suggested by Giovanni Battista de Rossi. In 1867 and 1868 he published two inscriptions from late antiquity, on either side of a marble slab:

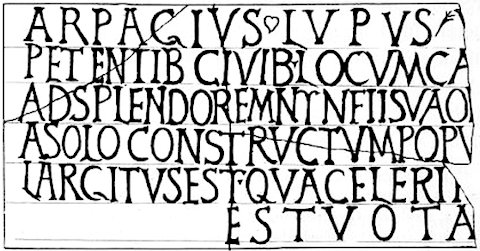

ARPAGIVS LVPVS V[(ir) c(larissimus?) ---]

PETENTIB(us) CIVIB(us) LOCVM CA[---]

AD SPLENDOREM NYNFII SVA OM[ni impensa?]

A SOLO CONSTRVCTVM POPVL[o ---]

LARGITVS EST QVA CELERIT[ate ---]

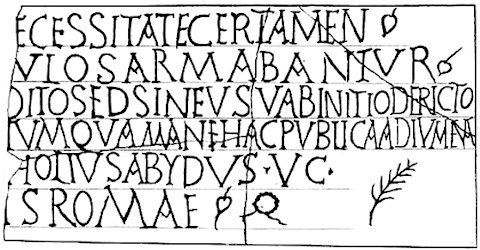

EST VOTA [---][--- n]ECESSITATE CERTAMEN

[---]VLOS ARMABANTVR

[---]DITO SED SINE VSV AB INITIO DER(el)ICTO

[---] NVMQVAM AN(t)EHAC PVBLICA ADIVMENTA

[--- Ac]HOLIVS ABYDVS V(ir) C(larissimus)

[--- praefectus annonae? urb]IS ROMAEInscription found in Portus, now in Rome, Villa Albani, side A.

EDR150122; PLRE I (1971), 521. Image: BullArchCrist 1867, 74.Inscription found in Portus, now in Rome, Villa Albani, side B.

EDR150121; PLRE II (1980), 4. Image: BullArchCrist 1867, 74.De Rossi argues that the two inscriptions refer to the same building. From side A he deduces that Arpagius Lupus, at the request of the citizens, erected a building (locus ca...) near a nymphaeum (understanding line 3 as ad splendorem nymphaei). Side B mentions activity by Acholius Abydus, perhaps Prefect of the Food-Supply of Rome. It seems to mention people who were furnished with weapons for a compulsory contest, and a place that was not used and deserted from the start, now converted for the public assistance. De Rossi then reminds us of a law in the Codex Theodosianus from 325 AD, by Constantine:

Cruenta spectacula in otio civili et domestica quiete non placent. Quapropter, qui omnino gladiatores esse prohibemus eos, qui forte delictorum causa hanc condicionem adque sententiam mereri consueverant, metallo magis facies inservire, ut sine sanguine suorum scelerum poenas agnoscant. Bloody spectacles displease Us amid public peace and domestic tranquillity. Wherefore, since We wholly forbid the existence of gladiators, You shall cause those persons who, perchance, on account of some crime, customarily sustained that condition and sentence, to serve rather in the mines, so that they will assume the penalty for their crimes without shedding their blood. Codex Theodosianus XV,12,1. Translation Clyde Pharr. De Rossi then suggests that line 2 of side A should be supplemented as locum caveae amphitheatralis, or, better, as locum castri or campi gladiatorii. It would not have been an entire amphitheatre, but a ludus gladiatorius, where convicted criminals had to fight. Arpagius Lupus would have built it around 400 AD (the last known gladiatorial combat in Rome took place in 404 AD). In the late fifth or early sixth century Acholius Abydus would have converted it for public use. Paul-Albert Février, writing in 1958, understands side A as a reference to the construction of a nymphaeum. In that case we could think of an earlier ludus gladiatorius. Was it the amphitheatre-shaped building 4?

Reconstruction of the amphitheatre-shaped building 4. Image: Portus Project.Behind the hemicycle of the amphitheater-shaped building was building 6, a row of rooms with walls and floors decorated with painted plaster and marble. One of the rooms was a three-seater latrine. A marble head of Ulysses or a fisherman was found in this building. Further to the west was a garden or courtyard.

Head of Ulysses or a fisherman, as it was discovered. Photo: Portus Project.

Head of Ulysses or a fisherman. Photo: Portus Project.To the north-west is building 8. It must have had three storeys. The ground floor consisted of vaulted rooms illuminated by windows, and with a cistern. The rooms of the first floor are arranged around a courtyard. The first floor rooms were richly decorated from the Trajanic period onwards, with polychrome and black-and-white mosaics and marble veneer. Latrines were found on the ground floor and first floor. A lead stamp was found in the building, dated to the late second century AD and linked to the marble trade. It may have been used by the staff working for the procurator of the harbour, registering incoming and outgoing ships, allocating mooring bays, coordinating the unloading and registration of cargoes, allocating warehouse space and collecting customs dues (portoria) from the incoming ships.

Building 8. Photo: Portus Project.

Building 8. Photo: Portus Project.

Building 8, the excavation of a latrine. Photo: Portus Project.Between the early fourth and early fifth century the amphitheatre-shaped building was demolished, to create an open area once more. In the later fifth or sixth century the Imperial Palace and building 5 were incorporated in a newly built city wall. It included a city gate that was later blocked, perhaps during the Gothic wars, in 537 AD. To this late period also belong some burials.

The excavation of a burial. Photo: Portus Project.Sources

- See the online bibliography, keyword "Portus - buildings - Palazzo Imperiale", plus Fea 1802, 39; Nibby 1827, 91; Texier 1858, 40-49; Lanciani 1868, 170-175, 187; De Rossi 1868, with illustrations in 1867; Ross Taylor 1912, 36-37; Calza 1925, 66-68; Lugli-Filibeck 1935, 87-90, 96-100; Février 1958, 319; Meiggs 1973, 163-165; Keay et al. 2005, passim; Keay et al. 2021, 378-379; Keay, interim reports in PBSR 2007-2019.

- Forthcoming is: S. Keay - G. Earl - F. Felici, Uncovering the Harbour Buildings. Excavations at Portus 2007-2012, Volume I. The Surveys, Excavations and Architectural Reconstructions of the Palazzo Imperiale and Adjacent buildings, British School at Rome Studies, Cambridge University Press.